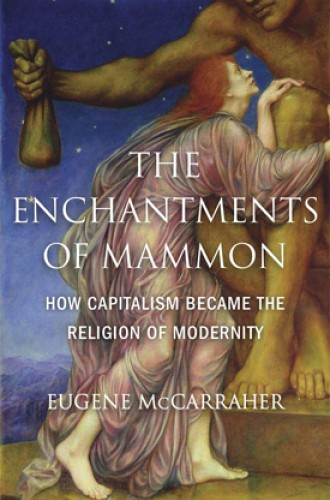

The deep roots of America’s enchantment with capitalism

Eugene McCarraher explains how money became our object of worship.

Imagine a world run on magic. Light shines from the sky although nobody pays it to do so. Herbs yield seeds, and fruit trees yield fruit—after their own kind, bizarrely enough. This world is populated by people who dream and think and want, using nothing but a piece of electrified pink meat lodged in a bone case behind their eyes. New people in this world require painstaking attention, and yet they are so compellingly globular that adults can barely help paying it. Everything meshes together like a conspiracy.

After a while, the people in this world get tired of relying for their self-continuance on a set of processes they can’t make sense of. They task a guild of warlocks with writing down all the steps of all the processes in words (words themselves being among the things that need explaining). After several centuries, the warlocks have gotten pretty good at it—so good that the citizens of this world begin to describe themselves as disenchanted, bereft in a world without magic.

This story underlies most accounts of the transition from the medieval to the modern world, of the rise of Protestantism, capitalism, and science. It’s a story that’s told by Marxists and capitalists, philosophers and sociologists. And Eugene McCarraher destroys it.