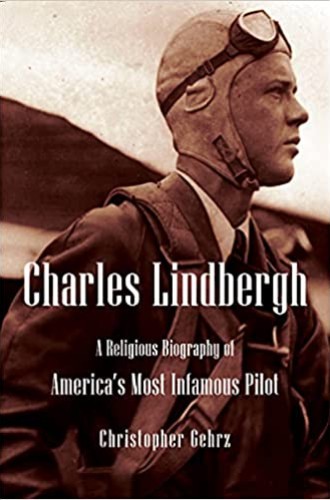

The complicated Lindbergh

It’s hard to strike the right balance in a biography of the heroic aviator and antisemitic activist. Christopher Gehrz succeeds brilliantly.

On Sunday morning, May 22, 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh, not yet 26 years old, awoke to find himself “the most famous man in the world.” In the previous two days he had flown the Spirit of St. Louis, a single-engine monoplane, nonstop from New York to Paris. During the 33.5-hour trip, the young pilot battled rain, icicles, and fatigue. At one point the plane dipped to ten feet above the waves. By universal assent it was a feat of extraordinary bravery.

Though Lindbergh was not the first person to soar across the Atlantic, he was the first to do it alone. When he touched down just before midnight, 150,000 fans were lining the runway. Back home, President Calvin Coolidge bestowed the Congressional Medal of Honor on him, and New York City feted him with a ticker-tape tape parade. One journalist said that the crowds behaved as if the “Lone Eagle” had walked, not flown, across the ocean.

Lindbergh may well rank as the brightest star in the galaxy of 1920s celebrities, a group that included Louis Armstrong, Jack Dempsey, Greta Garbo, Aimee McPherson, Babe Ruth, and Billy Sunday. But while the other celebrities remain in Americans’ collective memory basically for one thing—jazz, boxing, acting, healing, baseball, and preaching, respectively—Lindbergh lingers for a host of reasons.