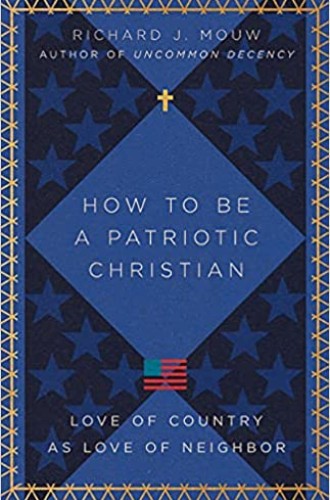

Nowadays many readers are likely to look down their noses at any book that appeals to patriotism. Loyalty to some corner of humanity seems parochial, a betrayal of morality’s commitment to all people. With this book, evangelical theologian Richard Mouw is likely to reach a different set of readers: those who see God and country as practically one. For many evangelical Christians, loyalty to God entails loyalty to country. Mouw defends patriotism but emphasizes that the patriotism proper for Christians gives highest loyalty to God; other loyalties must bend to that one. Christians must be ready therefore, to speak against—as well as for—the policies and direction of the country they love.

The argument may seem quite middle-of-the-road, and it is. But today in Christian circles, it actually needs to be made. For one thing, Americans who worship with the Stars and Stripes on prominent display—a commonplace, as everyone knows—slip easily into unthinking alliance with their flag-waving leaders. For another, with politics now so infected by anger and distrust, Americans just as easily slip into paralyzing—or sometimes violent—cynicism. For still another, Americans who consider Jesus a purely “personal Savior” often veer toward an individualistic faith that is indifferent to political concern. In all of these ways, true love of country seems compromised, practically inoperative.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Then again, does love of country make sense at all, given God’s claim on our highest loyalty? On this point, Mouw invokes the French activist and philosopher Simone Weil. After Christ had, as she put it, taken “possession” of her, she looked again at her relation to the French nation, then terribly compromised by its cooperation with Adolf Hitler. Weil argued that there is a human need for the particular loyalty we associate with patriotism. Knowing, however, the power of a wrong, or thoughtless, love of country, she sought something more responsible.

True patriotism, she concluded, is “inspired by compassion.” Just for that reason, it must be at once truthful, acknowledging of national flaws, and open to the sadness that accompanies such truthfulness. You see your country as “beautiful and precious,” and you see it as “imperfect” and “frail.” These words of Weil, Mouw writes, “capture my own experience of being an American.”

How to Be a Patriotic Christian is aimed, then, at the American context. It makes its case in nine short chapters over 150 pages, all of them replete with the author’s trademark clarity and grace. Mouw is confidently pro-patriotism, but only so long as patriotism is God-chastened and open to revision. His book itself, he says, is a “work in progress.”

In the early part of the book, Mouw reflects on the trappings of patriotism—the songs, parades, monuments, classic speeches, and sacred documents—that bind people together as a political community or nation. These generate affection and loyalty, which Mouw calls “civic kinship,” while also building up the outlook and character traits appropriate to citizenship. The I-centeredness of human life, so rooted in sin and so exacerbated by the digital revolution, can of course deplete the good will and spirit of cooperation that true patriotism requires. Mere civility is hard, let alone true care for the well-being of others. Flourishing together, Mouw emphasizes, involves “moral and spiritual work,” including prayer.

Mouw also considers familiar New Testament passages that bear on church and state: Mark 12:17 and parallels, Romans 13:1–4, 1 Peter 2:17, and others. Mouw takes these to bolster his point that the nation’s governing apparatus, or what he calls the state, deserves our tentative—that is, God-chastened—support. As for the state’s size and scope, he addresses that issue with a chapter-length reflection on the criterion of the common good. A “top-heavy governmental bureaucracy” can certainly undermine the common good. Still, parks, stop signs, police officers, and military protection matter; they enhance our shared lives. There is scriptural warrant, moreover, for the Constitution’s declaration that the government’s purpose is justice, domestic tranquility, the common defense, and the general welfare. These very themes come to expression when Psalm 72 describes the true work of kings.

Just past the book’s midpoint, Mouw makes two points that may be jarring to some readers. One concerns true patriotism’s openness to revision. He insists that perspectives not necessarily our own, even ones informed, say, by Marxist philosophy, are worth engaging. Bold conversation helps us correct our own “mistakes and misdeeds.” The other concerns expressions of patriotism in churches, including acknowledgment of national holidays during worship or display of the flag in the sanctuary. Here lies the threat of nationalistic pride, but in many congregations insisting on change would be ruinously divisive. One option, Mouw suggests, is to take these practices as “teaching opportunities” to open up discussions about patriotism.

Mouw also explains and defends the concept of civil religion. As famously expounded by sociologist Robert Bellah, this is the idea that the generic religious language familiar in the American political context, though potentially perverting, is on balance good for the country. Prayer at public meetings, chaplains in the military, the Pledge of Allegiance (with its “under God”) in schools—all these, rightly conceived, point us “beyond the status quo.” They remind us of values that transcend our merely human ones and underscore the ever-present need to reconsider what we think.

The book’s last chapter is where Mouw invokes the aforementioned Weil and offers guidelines for helping us wrestle further with the issues. Go deep, he says, with both your thinking and your compassion. His final guideline is: “Trust Jesus,” and here we may consider a remark he makes in the book’s first chapter: trusting Jesus is just what Mennonites and others in the Anabaptist tradition, whom he describes as dialogue partners, take with “utmost seriousness.” But they would, Mouw allows, object to much of what he says.

One reason, unremarked in his book, is that the Anabaptist tradition not only trusts Jesus but also makes his Sermon on the Mount central to Christian perspectives on the state. In How to Be a Patriotic Christian, Mouw does not. Certainly (but for a brief defense of swearing oaths) he does not wrestle with the crucial passages in Matthew 5. For someone in dialogue with neo-Anabaptists, this seems a major oversight. Mouw’s take would no doubt be thoughtful, even formidable, but here he leaves his readers hanging.