For BLM cofounder Alicia Garza, organizing is about doing the work no one wants to do

Someone has got to do the dishes.

The world today seems to be falling apart, and yet the communal mood I most often encounter is not bleak hopelessness, malice, or even malaise. I more often witness a defiant desire to “do something,” anything, to stop others’ unjust sufferings. At protests or online, most people express a wish to honor the dignity of other people’s lives, to help keep others alive and well. The question hanging over everyone’s head is: How?

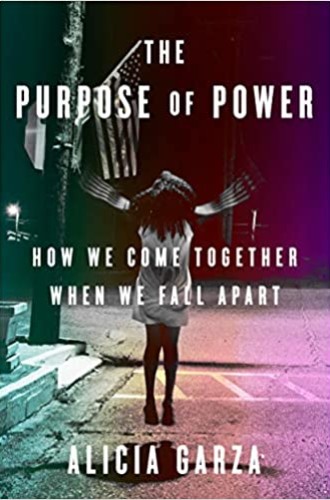

Enter Alicia Garza. She’s most famous as a founder of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, but her work extends far beyond social media. As a community organizer with decades of experience, Garza lays a hand on her readers’ shoulders while going over where we have been and what we can do now that will make a difference.

“Dignity and survival are our core concerns,” Garza writes, and she repeats this message throughout the book. These two priorities sound simple. But Garza opens with her own personal story and the context of her time—namely, Reaganism and the suffering it has caused for Black people for decades—and in doing so she shows how truly difficult these goals are to achieve for far too many.

She emphasizes that empowerment is not the same thing as the power to truly change injustices. The former is a feeling, while the latter requires work. Power, she says, is “the ability to make decisions that affect your own life and the lives of others, the freedom to shape and determine the story of who we are.”

Often this work entails knocking on doors, one by one. Repeatedly. The essence of community organizing is “building relationships and using those relationships to accomplish together what we cannot accomplish on our own.” Social media alone cannot make a movement. Engaging followers does not produce long-lasting change. Relationships founded upon specific short-term or long-term goals do.

Change cannot occur by one person’s efforts alone. “Organizations are a critical component of movements—they become the places where people can find community and learn . . . to take action, to organize,” and to form alliances, even with those whose priorities are very different from our own.

Faith leaders ought to take caution in forming alliances, though. In the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, following the police shooting of Michael Brown, Garza explains, traditional Black faith leaders like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton “were deposed because of the kind of leadership they tried to exert.” Both of them underestimated the anger and trauma of the crowds. Jackson “gathered a crowd and asked for donations—for the church,” and Sharpton encouraged the protesters “to calm down and vote.”

Both Jackson and Sharpton were criticized for responding too mildly in Ferguson, and in this sense,

the Ferguson rebellion marked a major shift, a moment when Black protestors stopped giving a fuck about what white people or “respectable” Black people thought about their uprising. . . . Had Black Lives Matter or the Ferguson rebellion or the subsequent Baltimore uprising heeded . . . advice about respectability . . . there would have been no uprising, no reckoning, no calling to account.

Too often, faith leaders see ourselves as the heroes, walking in step with the likes of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Dorothy Day, Arundhati Roy, and the Dalai Lama. A nostalgic view of these leaders can cause a kind of pastoral movement tourism. I have seen people of faith show up for a day of protests, volunteer once in a crisis, and maybe even gain an online following after a stirring speech. None of that is organizing. For a movement to succeed, leadership must be embedded in and responsive to the community, before and after a crisis. Change happens, Garza explains, “through sustained participation and commitment with millions of people over a period of time, sometimes generations.”

Garza makes mistakes, too. Her examination of patriarchy includes terminology that is confusing even to me, a nonbinary person. I do not understand why anyone in the LGBTQ community (as Garza identifies herself) would write “male-bodied people” and “woman-identified people” in a single sentence. It reads as two references, both outdated, to trans women. I wish Garza had taken the time to say that trans women are women, trans men are men, and nonbinary people are who they say they are.

That said, Garza makes it clear throughout her book that a mistake can be corrected and relationships repaired, so long as we are committed to each other’s dignity and survival. And she clearly is.

As a former organizer (although a far less successful one than Garza), I can attest to how hard it is to do the work she writes about. I have heard it said among faith leaders: “Community is about doing the dishes. We have to do the work that no one wants to do.” Yet when it comes to organizing for social change, more often than not I do not find people of faith doing the dishes. Even when some do, others refuse to see the value in the patient, mundane process of justice work expanding over several years—and sometimes lifetimes.

When the question of how goes unanswered, there are usually mistakes, infighting, lack of strategy, and empty rhetoric. “It breaks my heart,” Garza writes,

to see activists and organizers lashing out at one another, angry about money and power and credit, acting out our traumas over and over again. . . . Self-awareness and tools for dealing with trauma . . . are one part of the battle; the other part is healing the systems that create inequity and feed on trauma.

Does this not describe religious organizations as well?

Garza speaks to liberal faith leaders who wonder why we can’t just get along; Gen Z influencers who seek to harness an online following to change hearts and minds to save the lives and dignity of loved ones; organizers for a union, community, or cause who are continually hitting roadblocks; old-school conservatives questioning how to move forward (or wondering why Reagan invokes such pain among others); and those who have attended protest after protest, volunteered again and again, and seen nothing change. The Purpose of Power is for everyone.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Doing the work.”