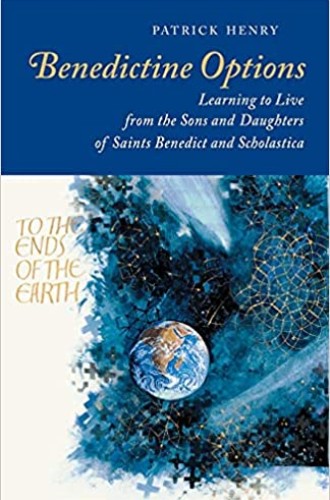

Benedict options learned from actual Benedictines

Patrick Henry’s vision of monasticism is not a fleeing ark, but a marsh teeming with life.

Patrick Henry offers a nuanced interpretation of how monasticism can offer a compelling critique of—and an alternative to—contemporary culture. In contrast to Rod Dreher’s doctrinaire assertion of the Benedict Option, Henry urges “Benedictine options” in which monasticism is not monolithic and culture is neither irredeemably bad nor completely without fault.

The Benedictine monasticism that Henry describes reflects the wisdom of the Rule of St. Benedict, which is moderate and inviting. For Henry, the Rule and monastic experience offer a discipline that, like good poetry, creates a structure for creativity and diversity in human life. Henry thus answers Steve Thorngate’s call in his Century review of Dreher’s The Benedict Option (May 8, 2017) for someone to “articulate a progressive Benedict Option, a separate project parallel to Dreher’s.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But this book is much more than a parallel project. Henry’s view of Benedictine monasticism reflects years of experience with actual Benedictines, and he offers a Benedictine monasticism that engages the world constructively because it is not conformed to the world. This engagement reflects a Benedictine charism that Henry describes as experimental, rhythmical, communal, ecumenical, and narrational.

As experimental, this monasticism is open to new possibilities and practices discernment. As rhythmical, it draws upon the depths of the liturgical year, the Psalms, and a balance between work and prayer (ora et labora). As communal, it embraces diversity within unity, a metaphor of the body of Christ. As ecumenical, it is a lay rather than a clerical movement, and it affirms identity without exclusion. As narrational, it weaves those first four gifts together in actual monastic living (stories) that is complex, concrete, and connectional.

Henry describes a monasticism that is confident without being arrogant, hopeful without being Pollyannaish, and realistic about human fallibility and corruptibility without being cynical. There is serenity—not from ignoring evil or pretending that everything is fine, but from being grounded in a way of life built for human flourishing that has endured for centuries.

Christians who live within the spirit of Benedictine monasticism do not heroically withdraw from the world to preserve themselves from a toxic world, Henry writes. Rather they enter a more modest (and human) project, “a school for beginners” as Benedict describes the monastery, in which they embrace discipline that offers balance in their own lives and also opens them to what is good in the lives of others. The world is neither forsaken nor uncritically embraced. The monastery is not an ark safely above threatening seas, Henry writes, but rather it lives within the ebb and flow of a saltwater marsh, refreshed by the sea, and hearing the bell of which T. S. Eliot wrote in the third of his Four Quartets.

Henry takes Dreher to task for both the narrowness of his vision of monasticism and his lack of experience with it. Apparently Dreher visited exactly one Benedictine monastery, a rather traditionalist community in Italy. Henry argues that this results in a view of monasticism that is quite truncated and more driven by ideology than actual monastic practice. In contrast, Henry offers wisdom from women Benedictines, insights from monastic traditions in other world religions, and his own experience with a number of Benedictine communities over the years. He emphasizes repeatedly that “Benedictine options depend on evidence of the actual lives of real Benedictines,” and such lives reveal a richly textured approach to Christian living that is not primarily about withdrawal.

In the final chapter, Henry introduces us to two Benedictines: Sister Jeremy Hall and Father Godfrey Diekmann. (Full disclosure: I had both of them as professors when I was an undergraduate at St. John’s University/College of St. Benedict.) They were both joyful people. The world for them was not “cold, dead, and dark” (Dreher’s words) but alive to possibilities for new life. Henry shows how both emphasized incarnation and resurrection in their theologies. Recognizing the need for redemption, for reawakening of what is inherent to us as created in the image of God, they delighted in the mystery of God’s gracious presence in human life, in human relations, and in the beauty of God’s creation. They saw that God’s work in our lives means that there will be surprises, that we should embrace life with the awareness that God’s love is at the heart of all existence.

Both showed in their lives that “Benedictine options,” as Henry writes, “aren’t locked in a box” to be sealed off from a contaminated world. Instead, they invite us into the messiness of the marsh, teeming with life.

Henry offers a compelling case for Benedictine options in which we accept Benedict’s invitation at the beginning of his Rule to listen as God speaks through the Psalms, through the disciplines of life in community, and through the strangers who arrive seeking hospitality and are to be “treated as Christ.” Such hospitality, not a hostility toward the world, Henry urges, will keep us open to how Benedictine options can enliven us and the world in which we live.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “To live as beginners.”