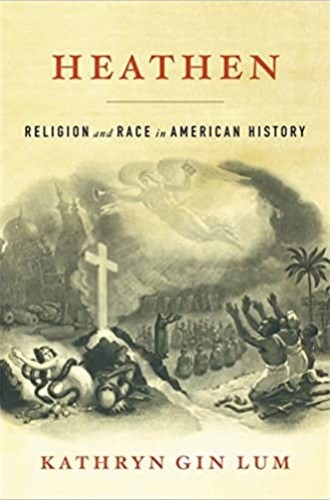

American “heathens”

Kathryn Gin Lum explores the entwining of racial and religious stereotypes in the United States.

Kathryn Gin Lum traces the American theory of the heathen, a word chosen deliberately for its negative and archaic quality. Heathens, according to a common and very powerful historical view, constitute an alarmingly large part of the world’s population. Beyond their spiritual ignorance, they suffer from grave physical and mental inferiority, and they have no hope of raising themselves by their own efforts. They can be elevated only by the dedicated and benevolent work of their superiors, who are White and Christian—and overwhelmingly Protestant. As they rise to accept the standards of that higher breed, suitably improved heathens can begin to make their way in the world. The goal of helping and improving these inferiors, whether they seek out such aid or not, is a fundamental building block of American ideology.

I am oversimplifying a complex argument, but this sketch gets to two other key points of Gin Lum’s argument. The first is the very early and constant overlap between race and religion in the US Christian vision. Despite some claims to the contrary, American views of the inferior outside world do not segue from religious to racial stereotypes; instead, the two are all but indistinguishable all along. Second, Gin Lum argues that this concept of the heathen is still very much alive and well, long after the actual vocabulary has become tainted and obsolete. It manifests in the easy and widely accepted division of the world into the fortunate and the benighted, which over the past century has usually been detached from explicitly religious groundings. We see it, for instance, in the language of the “third world.” The approach is fundamentally infantilizing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Gin Lum’s work ranges broadly across authors and genres, particularly as she highlights figures who appropriated the heathen label for their own purposes in order to turn it back against the White empires. She makes skillful use of such powerful writers as the Yankton Dakota author Zitkála-Šá and Martinique’s Aimé Césaire.

This broad scope allows her to cover themes and approaches that would have escaped the attention of a less ambitious scholar. For instance, Gin Lum stresses the importance of anti-Catholicism in the story she tells, incorporating it extensively and thoughtfully. It’s a crucial topic because it illustrates the application of primitive and non-White heathen stereotypes to peoples who would, over time, gain fully White status in the American social order. This demonstrates the highly fluid nature of such categories: Whiteness changes and evolves, and so does heathendom.

Heathen offers a dazzling range of examples to substantiate its thesis. Rare is the reader who could dip into it without becoming much better informed on a great many topics historical, literary, and religious. So many of Gin Lum’s examples are enlightening and informative in their own right.

I inevitably had some disagreements. When I teach about global Christianity, I often use Charlotte Brontë’s 1846 poem “The Missionary” to explain what drove those evangelistic endeavors. The poem perfectly epitomizes the view of those overseas races as “the weak, trampled by the strong,” who “live but to suffer—hopeless die.” They are subject to “pagan-priests, whose creed is Wrong, / Extortion, Lust, and Cruelty,” until they can be liberated by White Christians. This is exactly the thought world of Heathen, and the poem vividly illustrates the overlap of racist and anti-Catholic rhetoric.

Quite reasonably, Gin Lum does not quote Brontë’s poem, because it is not American and therefore falls outside her purview. But that in itself raises an issue. Are the attitudes and concepts explored in Heathen in fact distinctively American, or did they rather belong to a much broader phenomenon which was more generically Protestant—emphatically British, but also German and Northern European?

But surely we would also find very much the same ideas among Catholic imperial and missionary powers, especially the French and Belgians. It was these ideas, above all those of imperial France, that provoked the ferocious responses that Gin Lum quotes at some length from Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon, even if those authors did on occasion throw in obligatory denunciations of the United States. From an African or Caribbean perspective, it was the European (and European Christian) views of heathens that mattered, and it is confusing to see anti-colonial responses presented here as if they were specifically blows against American empire. For those reasons, I do not agree with Gin Lum’s portrait of the American trajectory as in any way exceptional.

Heathen must also make the reader think carefully about “helping” in general. The author’s complaint is that the American impulse to help inevitably casts the rest of the world as helpless, needy, and awaiting uplift. But surely, whether we are looking at the world of 1860 or 1960 or 2022, a very substantial chasm really did (and does) separate different regions of the world in terms of wealth, power, and access to resources. That global gulf can be measured by any number of objective measures. Whatever we call them, very poor nations suffer multiple kinds of deprivation, which are long forgotten in the world of the WEIRD—Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic.

Gin Lum is absolutely correct to reject the idea that the poor heathens cannot lift themselves by their own unassisted endeavors. Of course they can: just look at some of the so-called third world nations of the 1960s, such as South Korea, Taiwan, and China. But what are the proper obligations of the United States, and the rest of the WEIRD world, to the still extremely poor? Can development work legitimately help, free of racial condescension? How should nations like the United States reconceive their efforts to help? And what might be the proper place of Christian churches and missions in any such enterprise?