What do we mean when we say something is “in the Bible”?

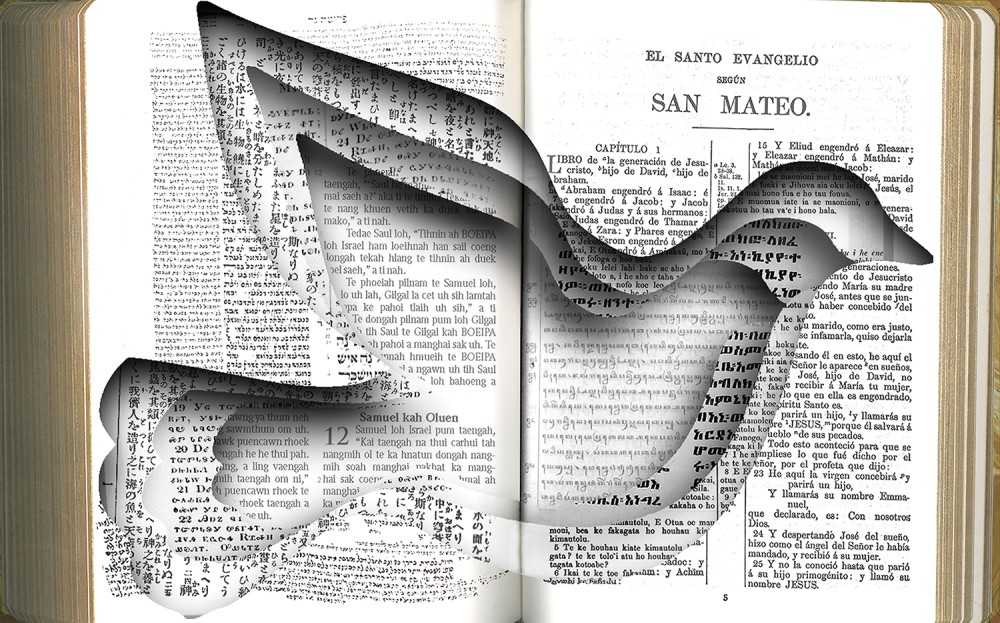

A new database of more than 900 biblical translations presents a prism of cultures, languages, and meanings.

Century illustration (Source images: Creative Commons)

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s classic novella The Little Prince has been translated into more than 600 languages and dialects, more than any other nonreligious work in history. Translation of this magnitude is truly a mind-blowing feat, a powerful and ever-growing monument to this beloved story of friendship, love, and seeing with the heart.

My own experience with Bible translation makes me wonder whether the English readers of The Little Prince, the Basque readers of the Printze txikia, and the Zulu readers of the Inkosana Encane are all reading the book in the same manner. Do they approach this book as an original book in their own language, or do they recognize its universal themes packaged into a World War II French pilot’s semi-autobiographical tale that was then successfully translated into their language? In other words, how do we view this text as we read it?

There are seven different translations of Le Petit Prince into English, but of course most readers are not going to go back and compare their favorite translation with the French original in detail. We just don’t read most literature like that. Instead, readers love the story and yearn for its message: deeper relationships that allow us to see things that are “invisible to the eyes.”