A theologian without a school of thought

Douglas John Hall was an important thinker who was deeply shaped by the company he kept—and by the labels he resisted.

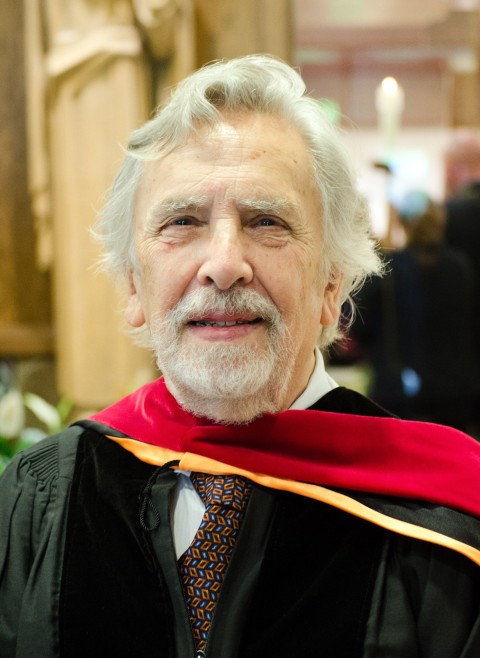

Theologian Douglas John Hall (Photo by Rhoda1929 / Creative Commons)

When Douglas John Hall died on April 10, we lost not only one of the most important North American Protestant theologians of the past 50 years but also the last prominent student of two of the great theologians of the mid-20th century, Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. John Bennett, Hall’s doctoral adviser and the former president of Union Theological Seminary, considered Hall the heir apparent to Niebuhr and perhaps the finest theologian the school had produced. And a certain poetry can be discerned in the fact that Hall died a day after the 80th anniversary of the execution of one of his theological lodestars, Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

It is nearly impossible to talk about Hall’s contribution to theology without reference to his influences, teachers, and peers. Outwardly, he could seem a singular and even lonely figure in theology, never consistently named alongside his contemporaries in terms of his significance (much to his chagrin). He often seemed to be waging an uphill, one-man battle for a theological vision that was, as he and his friend Jürgen Moltmann said of the theology of the cross they both championed, “not much loved.” But a deeper look into his life reveals a man who was deeply shaped both by the company he kept and the labels he resisted. Given that he titled his final book What Christianity Is Not, perhaps the best way to honor his memory is to take an apophatic approach to his legacy.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

That is all to say that Hall was much more complicated and sometimes contradictory than he often seemed, and for that, he and his work have at times been misunderstood. So rather than focus on individual books or specific dimensions of his thought, such as the theology of the cross or the collapse of Christendom, I want to posit that to appreciate Hall and his contribution fully, one must look not just at his thought and his output but at the man himself, a man who knew himself at heart to be a theologian.

One place to start is to consider the core course Hall taught at McGill University, where he spent the majority of his academic career: History of Christian Thought. Even as he is most often associated with 20th-century theologians, Hall’s theology is deeply steeped in the breadth of Christian history. It is also significant that his course title refers to Christian thought rather than Christian theology. For Hall, apart from human thought theology is, well, unthinkable. It never lives in a space of absolute certainty, nor is it fixed for eternity. It must always be read relative to the context in which it is thought. That applies as much to the church fathers and the Reformers as it does to contemporary thinkers.

Second, his contextual method, as he expounded in Thinking the Faith, has sometimes been misunderstood; it must be distinguished from those whose method is centered on social location and identity. One of the underlying questions of his work was, What happens when a theology that has been largely formulated in Northern Europe arrives in North America and makes its home there? For example, early in his career, when Moltmann’s Theology of Hope became a sensation in North American theological circles, Hall said that he was “not charmed” by that reception. In his unpublished quasi autobiography Not Hid from Thee, Hall writes, “I am convinced that very few American or Canadian religious leaders, including teaching theologians, actually read [it] . . . and fewer still asked themselves seriously whether such a song of hope, emerging out of the chaos and despair of post-War Germany, could be adopted by the English-speaking ‘winners’ without very serious adjustments and nuances. . . . Moltmann’s profound study was reduced, in hundreds of symposia, seminars, sermons, and journal articles, to a cliché” when it landed in North America. Hall doubted that a theology forged in postwar Europe, under the particular circumstances under which Moltmann returned to Germany after his experiences as a POW in Scotland, could translate easily to a North American context. Thus, Moltmann’s success helped drive Hall’s own project of describing a theology that was true to the North American context.

Third, Hall always resisted those who would place labels on his work, and he never identified fully with any particular school of thought. His early devotion to Karl Barth (whom he met and whose American lectures he once attended) led many of Hall’s seminary classmates to identify him as neoorthodox. But Hall’s interest in Barth had much to do with Barth’s early association with the Confessing Church in Nazi Germany; he rejected the much more rigid approach Barth later adopted. Echoes of Hall’s teacher Tillich can be found throughout his writings, but Tillich’s nontheistic approach was never a fully comfortable fit for Hall. He was proudest to be associated with his teacher Niebuhr, and he maintained a lifelong friendship with Niebuhr’s widow and children. But calling him Niebuhrian is perhaps too reductive. Hall’s work is less explicitly political than Niebuhr’s, and it self-consciously speaks to a different context.

Nor does Hall totally fit within any particular genre of theological work. While his three-part series Christian Theology in a North American Context addresses the standard systematic tropes, the work is hardly a standard systematics; Hall cannot rightly be called a systematician. Nor is he particularly interested in dogmatics, despite his historical bent and orientation to the church. He perhaps is best set with the constructive theologians, though he was not often included in their ranks. In Not Hid from Thee, Hall writes,

I have never felt entirely alone as a theologian. . . . All the same, I know that I have had to struggle through to whatever insights I have had as a theologian, and to do so, in some real sense, “on my own.” . . . I have not been part of a “school,” however much I learned from my teachers and from the whole, long tradition of Jerusalem. I had to muddle my way through to this or that illumination, because I had to do it as the human being that—for better or worse!—I actually am: a Canadian, living at the end of the 20th century and into the beginning of the next, conscious of its being also the end of “Christendom” and maybe even the end of Western Civilization. My thought bears all the earmarks of that struggle, hopping from one little stepping-stone to the next, and conscious of the pitfalls all about me. I have never had the benefits of being part of a doctrinally-definitive community. . . . Perhaps I have been too much a loner—and I know that that is not without its deeply psychic connotations. I have often felt uncertain of myself, and sometimes (especially in the midst of writing major pieces) I have wondered how I could possibly have the gall to pursue such lines as came to me! Yet I felt—and feel—that I should trust my own intuition, and be led (as more pious souls would put it) by the divine Spirit, or at least hope that the Spirit leading me was divine and not demonic!

And though he is no dogmatician, the “school” that most readily defines Hall’s work is the church. Hall knew his primary audience to be the leaders and pastors of the Christian church, and he tuned his voice to that audience. It is perhaps because of that ecclesial orientation that he sometimes goes unnamed among other, more academically oriented theologians who are more easily identified with particular schools of thought. It is not for nothing that each title in his three-volume magnum opus references “the faith.”

But it is also here that his seeming contradictions can be most recognized. Despite his lifelong membership in the United Church of Canada and his early pastoral career, Hall never established a fully satisfactory congregational relationship, at least not during his time in Montreal. Even though he belonged to a primarily Reformed denomination, his works rarely reference John Calvin or other historical Reformed figures. His thought was much more informed by Martin Luther, and he found greater popularity in US Lutheran churches and seminaries than he did in the institutions of his native Canada.

Some of his contradictions are admittedly problematic for many of us who are otherwise shaped by his work. Any movement or school of thought that came with an “-ist” or “-ism” suffix attached aroused his suspicion as being inherently ideological (except for, curiously, socialism). For instance, he was an early adopter of gender-inclusive language and employed it masterfully and naturally, and he was deeply supportive of women in ministry and academia. Yet he steadfastly refused being identified as a feminist, as he regarded much Christian feminist thought as more ideological than theological. At the same time, he counted such noted feminists as Rosemary Radford Ruether, Dorothee Sölle, Phyllis Trible, and Sallie McFague as respected friends.

Similarly, he was a longtime supporter of homosexual (his preferred term) inclusion in church life and ministry and spoke often of sexual fluidity as a natural dimension of human experience. But in private, he sometimes conflated sexuality with sex, and he was not entirely comfortable with same-sex relationships or people openly identifying as gay, including his mentor Robert Miller and his dear friend Gregory Baum. This was not simple homophobia but rather a place where Hall’s theological convictions sometimes came into conflict with changing understandings and personal experience. His definitions of what theology entails—and, more importantly, what it doesn’t—sometimes narrowed the scope of his theological vision.

But ironically, those very misunderstandings, complications, and contradictions leave his theological legacy much more open to continual reappraisal and reappropriation than that of many of his peers. As I suggested in my contribution to the 2020 edited volume Christian Theology After Christendom: Engaging the Thought of Douglas John Hall, the future of Hall’s project lies not in trying to preserve his writings in amber but in applying his own contextual method to his writings. We must continually decontextualize and recontextualize his oeuvre, taking his work apart so that his writings speak not only to one another but are also put into conversation with other, newer voices. We have barely begun to plumb the depths of what Hall has left us.

Those of us who mourn his death most deeply did not just admire him as a thinker. We knew him as a friend, and as a friend he was unambiguous in his loyalties. As lonely as he sometimes seemed in the theological world, I suspect that few of his peers were as deeply beloved by those who knew them. He loved corresponding with us, challenging us, and professing his faith. He was astonished to have been granted as many years as he had, especially after multiple bouts with cancer. Even as his body became frailer and he deeply mourned the death of his wife, Rhoda Palfrey Hall, he was nevertheless able to live more or less independently in his longtime home in Montreal, and his intellectual powers remained intact to the end.

In mid-2024, Hall sent me a brief poem and explanatory essay that he described as likely his last theological writing, titled “Theologian.” The essay closes with these words, which aptly capture the man whose death we now mourn: “My life seems to me, more and more, a miracle and a mystery. . . . I am very surprised by, and truly grateful for, the long life that has been given me. At 97, I want to pursue it still joyfully until my days are all completed. I have tried to be—and I believe that I have been, at least in some degree of authenticity—a theologian.”