The church has a DEI problem

We love diversity. That doesn’t mean we’re willing to make room for difference.

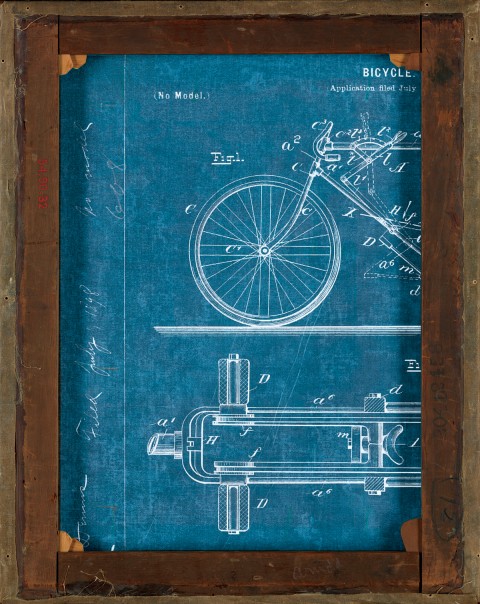

Century illustration (Source images: Public domain and Met Museum, NY)

I am that bicycle. You know, the one you haven’t gotten on in a while, and when you last tried it almost threw you off and you couldn’t get the gears to work? Stupid bicycle, you thought, what’s wrong with this thing?

I am that bicycle—me and many of my peers in ministry. We’re having a hard time working within church systems because we don’t work like those systems think we’re supposed to work, so they think we don’t work at all. Like a “broken” bike in the garage we sit there, our gifts unused, underused, or improperly used. We are the treadmills that become hanging racks for clothes, the “diamond finds” at thrift stores, the items that you got tired of and gave away.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The church has a DEI problem. The idea behind diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts is simple enough. We should do all we can to give our employees a comparable, fair experience at our company; no one should feel different. And we should work to make sure everyone outside our company has equal access to being hired; no one should feel left out. It’s really not hard to articulate, but it is hard to do—hard enough that many companies have entire departments and officers whose sole job is to hold the company accountable to being fair.

The rub is that many of these companies prioritize diversity in hiring—a good thing—but without also affirming a more fundamental truth that exists within this fairness project: people are different, and processes need to be in place to welcome people’s difference. If you focus just on diversity, then you tend to assume that people look different but are essentially the same. And so Black people and women (among many others) do get hired by a company, but then they hate working there because they are expected to work within processes and values that weren’t made for them. The implicit message is clear: You’ll thrive here if you become a White man.

It would be great if the church could wag its finger here—be prophetic or something—but, no. We have the same problem. We’d love to be more diverse—or in contexts like mine, we exploit our existing diversity as a brand promoting our progressiveness—but the place isn’t willing to change or make room for the new processes and values people bring.

For example, we want more young pastors, but when they won’t work 80-hour weeks or be on call 24/7 or neglect their other duties and interests, we question their commitment. The truth is that many of our churches fail to thrive not because of poor leadership but because of good leaders who are choosing health over dying inside a broken and archaic system. I, for one, am trying my best to imitate Jesus’ life and resurrection in my body, but not his death. I believe in the church with my heart and soul—and if I am foolish for doing so, dub me “Corinthians foolish”—but I’m not going to break myself to make a part of the system work that simply doesn’t anymore. And for that, me and others like me are often treated as ill-fitting and underfunctioning.

But I come from the Nintendo generation. If you put the cartridge in and it didn’t work right away, that was only the beginning of the work. You had to blow and wiggle and cast incantations on that gray box before it began to function—it was a sacred handshake. The lesson is the same for existing congregations and incoming church leaders: we work, but you have to know how to work with us.

Systems have to not only change but also make room for new ways of practicing leadership, community formation, and spirituality as a whole. There are going to be some people who want to pastor your congregation but need to obliterate the hierarchal structure to feel truly seen. There are people who will chair your committees as long as they’re not called “committees” and “chairs.” There are people who are deeply committed to spending their lives living out a commitment to Jesus and the church universal—and who are also neurodivergent. So they don’t always show up on time, or they laugh when others think they shouldn’t, or they can’t look you directly in the eye and give you a straight answer.

My point is this: The people I’m talking about aren’t being disrespectful or aggressive. It’s not that they “are not with the team.” They’re being themselves, and instead of counting it against them, we ought to be shifting how we do things to make room for them.

If that sounds hard, it might explain one reason so many companies are giving up on DEI. As a pastor, I’ve learned the hard way how easy it is to miss who someone is. I’m inviting you to join me in repentance, in hopes that God’s glorious church—the greatest institution there ever was—can do better at making room for those outside whatever your status quo may be.

Because they’re here already. And it’s not them that need to change; it’s us. The future of the beloved community depends on it.