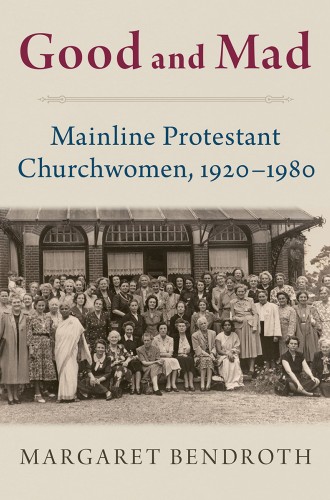

The complicated women of mainline Protestantism

Margaret Bendroth tells the stories of mid-20th century women who fought patriarchy from within the church.

With its narrow focus, this book may not reach a large audience. But I suspect it will, in years to come, be referred to as groundbreaking. Margaret Bendroth is clearing a path on which others will follow.

She has been at this work for a long time. Her first book, Fundamentalism and Gender, 1875 to the Present, based on her dissertation at Johns Hopkins, was published by Yale University Press 30 years ago. There she first emphasized the complicated leadership role women have played in American Protestantism. By the first half of the 20th century, her research showed, “fundamentalists had adopted the belief that it was men, not women, who had the true aptitude for religion. . . . In fundamentalist culture, women became the more psychologically vulnerable sex, never to be trusted with matters of doctrine, and men stronger both rationally and spiritually, divinely equipped to defend Christian orthodoxy from its enemies within and without.” Fundamentalism and Gender uncovered many of the ways women were historically unseated from roles of authority in the church—both explicitly and implicitly.

With Good and Mad, Bendroth widens the investigation. She explains in the introduction:

Complicated women are hard to place in history, and perhaps especially so when it comes to religion. We like stories of rebellious feminists contesting the status quo, insisting on the right to preach and challenging religious bigotry. And who doesn’t enjoy a sensational outlier like Aimee Semple McPherson, Kathryn Kuhlman, or Madalyn Murray O’Hair? They are all important, clearly, and the more the better.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But such figures are not the focus here. Instead, Bendroth writes about feminist “women with religious commitments [who] may have been every bit as angry as secularists” but found ways to remain within their religious traditions and keep them alive. Nevertheless, she notes, “men are still carrying the main narrative, leading social reforms, writing and teaching theology, and directing denominational bureaucracies.” In this way, Bendroth begins to uncover what is usually passed over when we tell the stories of mainline Protestant churches and people in the 20th century.

Good and Mad points to very few household names, in an effort to expand our understanding of mid-20th-

century Protestantism and the role women played in it. Bendroth dove deeply into the archives to bring forth the portraits on display in these chapters, which include women such as Helen Barrett Montgomery, Anna Swain, Georgia Harkness, and Cynthia Wedel. Of course, century readers are a sophisticated bunch, so perhaps those names are not new to all. How about, then, Madeleine Barot, Ann Hibbins, Margaret Hodge, Theressa Hoover, Mary Ely Lyman, Maude Royden, and Thelma Stevens? They too receive ample treatment here.

Bendroth quotes from mission board records, historical society and seminary archives, 1920s issues of the Congregationalist magazine, and proceedings of early Sunday school teachers’ association meetings. This is a history of religion from the underside. Bendroth doesn’t return to the debate of which sex is (or, whether one sex is at all) more spiritually inclined but begins with the simple historical fact that “the majority of believers are female.” So Good and Mad is also a participant-focused history.

Bendroth gestures toward similar strands in the histories of Jewish and Roman Catholic congregational life in this country, leaving doors open so that others may follow. She discusses Jewish women and “the feminization dilemma” in the context of male-denominated early 20th-century American Judaism. She describes how Catholic laywomen found creative means of being “both loyal to the Church and convinced of its errors.”

True to the book’s title, the theme of anger returns again and again, introducing fascinating and psychologically sensitive moments into what is otherwise just history. Bendroth clearly reveals how much men were (and are) afraid of women and their power. The frustration and anger—or potential anger—of women make men even more uncomfortable. And “churchwomen’s anger is hard to see,” Bendroth says, which is why she sets out to reveal it. Most intriguing is a conclusion that comes at the end of the book: the anger of churchwomen “is the underside of loyalty—to God, to church, to husband or friends. Loyal churchwomen knew the open secret, that the church, at least in its everyday business, was female, and men at times window-dressing.”

For readers lamenting the decline of the mainline (“even the word itself . . . seems painfully ironic,” writes Bendroth at one point), this may be a book to buoy the spirits. It doesn’t focus on the hegemony of the days when elite White men held leadership within denominations as well as cultural and political power and influence. Rather, it focuses on the resilience present among the largely female lay Protestantism over that same time period. The decades from 1920 to 1980 are painful ones to examine, but in Bendroth’s hands they are revealed as more interracial, ecumenical, tolerant, international in scope, and enduring—largely because of women’s ways of leadership.