Christian Wiman’s stubborn, slippery faith

We need faith, Wiman suggests, because poetry isn't enough.

In 2003, Christian Wiman was named editor of Poetry magazine. He was 37, a burgeoning critic, and the author of a well-received book of poems, The Long Home. Editorial changes at literary magazines don’t often garner international fanfare, but this was different. Poetry had just received a $200 million bequest from Ruth Lilly, the pharmaceutical heiress. Such money was unheard of in the world of verse.

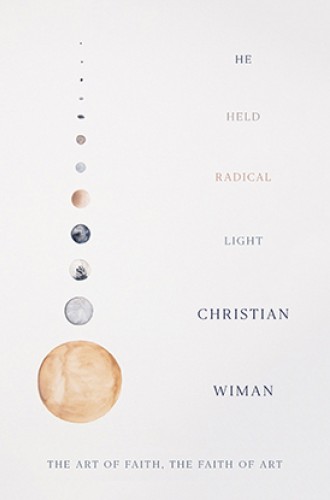

“To say that I was not equipped for this task is comically understated,” Wiman reflects. He was never comfortable with the significant bureaucratic elements of the position. In 2013 he left the magazine to teach at Yale Divinity School, a position that almost feels like destiny for him. Wiman is a poet, a thinker, a searcher. He Held Radical Light is a wonderfully meandering, pensive, and sometimes complex book-length essay on what it means to seek God in poetry and life—and to often end up empty-handed, or even empty-hearted.

Many of Wiman’s anecdotes come from his editorial years, including a strange story of Mary Oliver with a dead bird in her jacket pocket. There are a generous number of excerpted poems in the book: lines from Frank Bidart, Denise Levertov, Seamus Heaney, and A. R. Ammons make Wiman’s essay less a treatise and more of a spirited jaunt through the world of contemporary poetry. Even Wiman’s syntax is sinuous; you can ride sentences—gently corralled with em dashes—along routes that suggest a mind attracted to association.