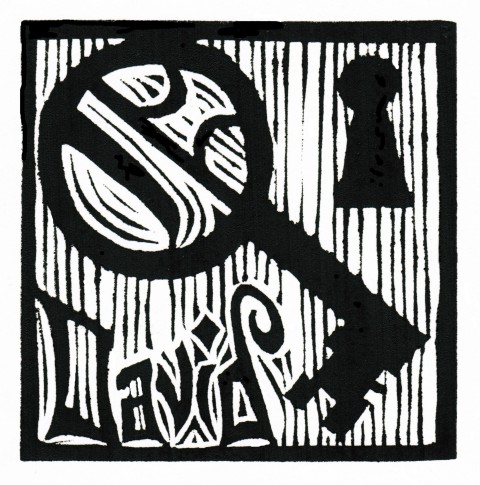

The key of David and other Advent images

Each December we pray for the key of David to come. What does it lock and unlock?

I’m writing this column in early November, but it will appear in the December 20 issue of the Century—a date that evokes “the bleak midwinter” of Christina Rossetti’s poem, and all the reflections proper to the last week of Advent.

By December 20 our tree will already be decked out from floor to ceiling with homemade and commercial decorations. I don’t see Advent as a liturgical fence to keep us from crossing prematurely into Christmas, as if the incarnation were a secret to be kept under wraps until the holy night. Nonetheless, the lessons and hymns of Advent train our hearts to keep Christmas in a quieter, more hushed register. My friend Sr. Johanna, a Benedictine nun, conveys the mood of the season in a poem that begins “In that long solemn moment of Before – / Before the dawn, when darkness always reigns . . .”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

To write for Advent, as for any of the great liturgical seasons, is to set aside the pursuit of originality for its own sake. The best Christian artists, poets, and theologians take their themes from scripture and tradition, and when they employ archetypal images—the darkness before the dawn, the key that unlocks frozen hearts, the fire of divine love, the morning star that heralds the rising sun—these tropes become new again. The familiar litanies of “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” sweep us along in cataracts of petition and praise. Our little coracles rise and fall on waves of inherited piety.

Yet what a rich inheritance! “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” opens the gates of Christian history, sending us back, by way of the Victorian divine John Mason Neale, to an 18th-century Latin hymn, and from there to the O Antiphons (or Greater Antiphons), sung before and after the Magnificat at Vespers on the seven days leading up to Christmas Eve.

The O Antiphons, miniature marvels of biblical typology, call upon Christ under seven prophetic titles—O Wisdom, O Lord, O Root of Jesse, O Key of David, O Rising Sun, O King of Nations, O Emmanuel—in a sequence which has a continuous history dating back to late antiquity. Boethius alludes to them in the sixth century, and by the eighth their use is well established. They are gnomic utterances, compact little spells that point to Christ by signs that lend themselves to poetic elaboration, from the magnificent Old English Advent Lyrics in the Exeter Book anthology (which gave Tolkien his mythic hero Eärendil, bearer of the morning star) to the Advent sonnets of the Anglican poet-priest Malcolm Guite, which are fresh and modern while remaining faithful to their prototypes.

Many years ago, dear friends of ours who live in Australia—at the summery antipodes to our bleak midwinter—gave us a set of four leaded glass medallions representing the first four O Antiphons. We attached them to the four branches of a lamp that hangs over our dining table, so that they float overhead and twirl like a Tibetan prayer wheel whenever a breeze or a tap disturbs them.

Today I’m pondering the O Clavis David medallion, the antiphon that corresponds to the date of this issue: “O Key of David and scepter of the house of Israel; you who open and no one can shut; you who shut and no one can open; come, and lead forth the prisoners from the prison house, those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death.” In this short verse, we hear Hezekiah speaking to his steward (“I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and no one shall shut; and he shall shut, and no one shall open,” Isa. 22:22) followed by the exultant words of Isaiah 9:2, all recast in the light of Christ. Evidently the O Clavis David is signaling, as an implication of Christ’s birth, the harrowing of hell we associate with Holy Saturday. No wonder that Alcuin, poet and polymath of Charlemagne’s court, took to reciting this antiphon when he sensed that death was not far off.

So this is what December 20 is all about, not just a prelude to our merriest feast but a petition to the redeemer—intensified by the vocative O and the recurring veni—to visit us now and release us from captivity to sin and death, to return to us in glory and remake the fallen world. Whatever chains confine us—of grief, or compulsion, or agony, or lassitude, or resentment, or disappointment, or fear—these are chains his key can unlock for us; whatever moral dangers threaten us, these are dangers from which from his lock and key can keep us safe.

All this is rendered in the familiar words of the hymn: “O come, Thou Key of David, come, / And open wide our heavenly home; / Make safe the way that leads on high, / And close the path to misery.”

The date of this issue has an additional significance for me, since it marks my last regular column for the Century. It’s been a wonderful 17 years, and a great privilege to be part of the Faith Matters team. I have always felt at home in these pages, thanks to the magazine’s gracious editors and generous readers. Heartfelt thanks—and merry Christmas!

A version of this article appears in the December 20 print edition under the title “O Key of David.”