Pauli Murray’s many identities

The first black female Episcopal priest was also an early proponent of ideas that would develop into black feminism, intersectionality, and more.

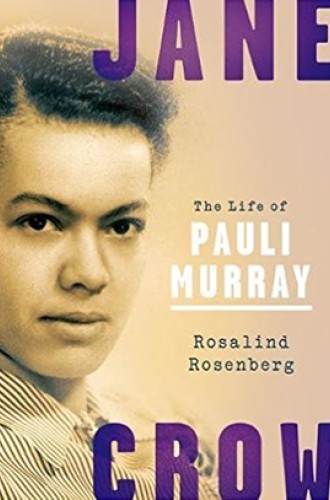

The life of Pauli Murray shows that one person can do a lot to fight discrimination and promote social justice. Barnard historian Rosalind Rosenberg tells the story of the first black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest—which was just one part of her trailblazing life.

Murray bridged multiple identities as a person “in between.” She was multiracial (black, white, and Native American), a woman who said she often felt more like a man and was attracted to women, a northerner and a southerner, both working class and middle class, and even left-handed but forced to learn to write right-handed. Although highly influential, she never arrived at a place where she had an easy life. Always on the move, she constantly fought uphill battles to redress arbitrary distinctions between people.

In working for many oppressed groups at once, Murray set forth several ideas that foundationally changed how people think. Perhaps her most important idea was the one referred to in the title—Jane Crow—the “double discrimination she faced as a black female.” Murray was one of the first to argue that gender is analogous to race, sexism is similar to racism, and gender discrimination can be targeted using the same strategies used to target racial discrimination.