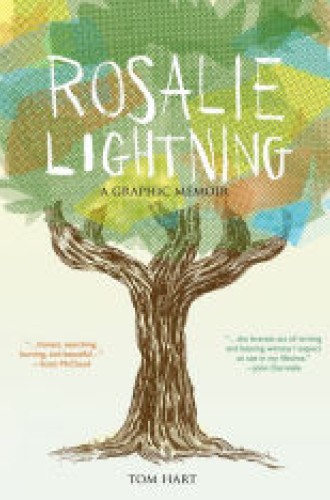

Graphic grief

Midway through his graphic memoir, cartoonist Tom Hart comes to an abrupt and pointed question: “What do you do when your child dies?” In the next frame, he answers the question: “You fall into a hole.” Hart’s meditation on grief gives the graphic details of how he and his wife, Leela, crawled out of that hole following the unexpected death of their toddler Rosalie.

The phenomenon of grief is hard to understand fully while experiencing it, in part because it is not a linear process that moves toward healing. Hart acknowledges this aspect of grief through his story structure, and through the combination of words and pictures, which allows him to depict multiple stages of grief at once. He structures his story around two dominant forms of thought in the West: Aristotle’s metaphysics and the literary genre of epic. Both of these features deepen Hart’s exploration of grief and allow him to give a fuller account of the process.

While no mention is made of Aristotle in the text, Hart begins and ends his story with oak trees and acorns, the same example that Aristotle famously used to illustrate the difference between actuality and potentiality. Hart’s use of this framing device does not feel like a philosophy lesson, for it comes from his daughter’s interest in gathering acorns and being in nature. At the beginning of the story, Hart and his wife collect acorns and remember Rosalie. At the end, Rosalie’s memory is depicted as an acorn transforming over several frames into a full-grown tree with its own acorns to drop.