Picturing dementia

Some 25 years ago my parents and one of their best friends, Gertrude, started showing signs of dementia. As their conditions worsened, Gertrude’s daughter Ann and I began trading morbid geriatric jokes. Laughing helped us face the daily struggles of caregiving: it felt so much better than crying.

In 2014, New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast published a graphic memoir about her aging parents that would have been perfect for Ann and me. Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? (which will be released in paperback this September) is often improbably funny. Its comic-strip presentation is poignantly true to life: frazzled caregivers will recognize themselves on every page, and they may also see aspects of their parents in Chast’s clueless father and ferocious mother. Chast’s drawings let us cry, and then they make us laugh—sometimes simultaneously.

|

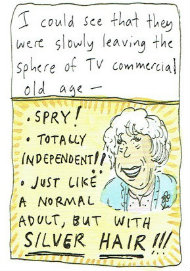

Her parents, she discovers, are losing their balance and their memory. They fall, drive dangerously, eat poorly, and have anxiety attacks. They end up in the hospital. They can no longer cope. Chast to the rescue! She manages their finances and legal documents. She moves them to a safe place near her home and cleans out the apartment they’ve lived (and hoarded) in for decades. She helps her father transition from assisted living to hospital to nursing home to hospice. She stands by her mother as she becomes incontinent, anorexic, and delusional.Chast’s caregiving begins the day she notices grime covering everything in her parents’ apartment—“not ordinary dust, or dirt, or a greasy stovetop that hasn’t been cleaned in a week or two,” but “a coating that happens when people haven’t cleaned in a really long time.” The grime shocks Chast into recognizing that something is seriously wrong: “I could see that they were slowly leaving the sphere of TV commercial old age (spry! totally independent! just like a normal adult, but with silver hair!!!) and moving into the part of old age that was scarier, harder to talk about, and not a part of this culture. . . . SOMETHING WAS COMING DOWN THE PIKE.” She begins making regular visits from her Connecticut home to their Brooklyn apartment.

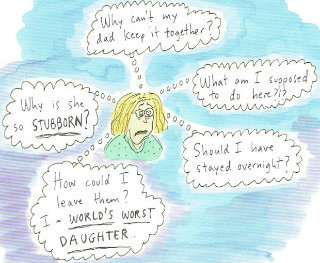

Much of the time, she feels like screaming. Sometimes she actually screams.

|

In her cartoons, Chast doesn’t just say that caregiving can make a person crazy: she displays her bared teeth, the dark circles and frown lines around her tired eyes, the smoke pouring out of her ears. She doesn’t just write that the frail elderly may be fearful or forgetful or irascible or loopy: she shows her father obsessing about his bankbooks (someone might steal them!), her mother ranting at the hospice lady. Her cartoons let you enter the story and say, Yes: that is what it’s like for me too. I am not alone.

The publishers of Graphic Medicine, a comic book series launched by Penn State University Press last year, know that “graphic narrative enlightens complicated or difficult experiences.” Put more simply: comics are therapeutic. The most recent book in the Graphic Medicine series, Aliceheimer’s, is by an artist-novelist-anthropologist who, like Chast, cared for her mother through years of dementia. Dana Walrath “was the daughter who got on her nerves. The feeling was mutual.” Yet it was Walrath who brought Alice to live with her in Vermont once the older woman became incapable of living on her own in New York.

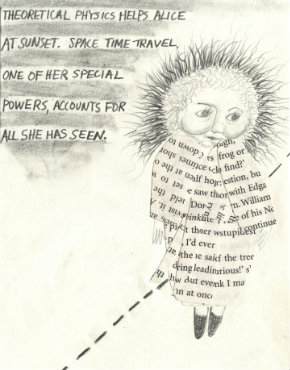

In Vermont, Alice plays Scrabble with made-up words. She searches for her deceased husband in a maple tree. She fears she has grown horns and hooves. She eats ravenously and constantly, especially ice cream. She loses bowel and bladder control. Walrath tells her mother’s story in 26 very short chapters (originally blog posts), each illustrated by at least one collaged drawing. Most of the drawings feature Alice wearing a bathrobe made of page fragments from Alice in Wonderland.

Why include pictures? Because people with dementia retain visual function even as they lose cognitive function, Walrath writes on her website, which means that she and her mother can enjoy the pictures together. Because “graphic storytelling captures the complexity of life and death, of sickness and health. Going back and forth between the subconscious and conscious, between the visual and the verbal, lets us tap into our collective memories, an essential element of storytelling. When we meet through story, we heal.”

Some of Walrath’s healing comes through reframing how she views Alzheimer’s. While Chast offers fellowship to the afflicted caregiver, Walrath offers an anthropological method for dealing with the disease. Observing Alice as if she belongs to an unfamiliar culture, Walrath relates to her in ways that respect her alternate reality. Her stories are mostly lighthearted; her drawings are whimsical, magical, surreal. They incarnate the current state of Alice’s mind: having fallen down the rabbit hole, she has entered a Wonderland where the year changes from moment to moment, where wicked witches hover, where laughing, singing pirates transport her by galleon to distant islands.

There is no point in trying to return Alice to Walrath’s world: she will not be moved. So Walrath learns “to make her stories and hallucinations safe, normal, not something to challenge.” When Alice sees someone who is invisible to everyone else in the room, Walrath says, “I can’t see her, but I’m sure you can. You have special powers. You can see things that we can’t.” When Alice is convinced that it’s 1945, food is rationed, and Japanese soldiers are surrounding the house, Walrath draws a picture of her serenely drifting skyward. “Theoretical physics helps Alice at sunset,” reads the caption. “Space time travel, one of her special powers, accounts for all she has seen.”

|

Yet even anthropologists have limits. When Alice, believing her “period” is over, removes the stuffing in her Depends with predictable results, Walrath and her family realize they can no longer care for her at home. It is time to move Alice to a memory-care facility.

Alice’s story is unfinished. At age 82, she is still living near her daughter in Vermont. Walrath’s book is about the middle stages of Alzheimer’s, not the entire course of the disease. By contrast Chast’s book, though it contains many frames about dementia, is about death. Her parents’ story, like all stories, begins in dust—layers of it in a Brooklyn apartment—and ends in ashes, with frequent appearances of the Grim Reaper along the way.

Chast’s father died first, at 95. Her mother died two years later, at 97 (Chast’s sketches—not cartoons—of her dying mother are heartrending). Their ashes repose in velvet-swathed boxes in Chast’s bedroom closet, “along with shoes, old photo albums, wrapping paper, a sewing machine, a shelf of sleep t-shirts, an iron, [and] a carton of my kids’ childhood artwork.” Someday, Chast thinks, she may find a more permanent place for them, but she still needs time to work out her relationship with her mother. Meanwhile, the closet “makes a nice home for them,” she thinks. “Every time I open its door, I see the boxes, and I think of them.”

Having cared for two parents with dementia, I identify more with Chast’s conflicted protagonist than with Walrath’s good-humored anthropologist. As a checkout clerk, noticing my pile of books about parent care, once wryly observed, “Been there, done that. You can’t do anything right!”

Still, I have nothing but admiration for the nursing-home employees who calmed my parents by entering into their alternate reality, no matter how bizarre (nurse to my father, relieving him of the stack of shirts he has filched from other residents’ rooms: “Would you like those shirts plain or starched?”). If I were buying parent-care books today, I’d put Chast and Walrath at the top of my pile—one for empathy, one for insights, and both for giving me permission to smile.

Images courtesy of Bloomsbury and Penn State University Press. Used by permission.