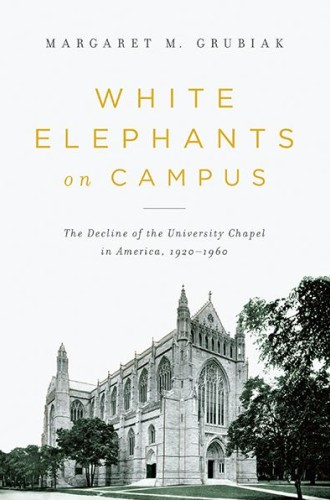

White Elephants on Campus, by Margaret M. Grubiak

The University of Chicago—a Baptist institution—began construction of its enormous Gothic cathedral of a chapel in 1926, ensuring that it could hold the entire student body for religious services, but in the midst of the multiyear construction project, the university stopped requiring chapel attendance. Princeton University—Presbyterian—began construction of its own massive chapel in 1925 during a decline of interest in mandatory chapel and a crisis of faith prompted largely by the heartbreaking losses of the Great War. Meanwhile, Congregationalist Yale opted not to replace its smaller, Victorian Battell Chapel with a triumphalist Gothic structure but rather to build that ecclesiastical and architectural musculature into its new Sterling Memorial Library, hence creating a “new cathedral” responsible for the “reshaping of religion.” Unitarian Harvard, in the meantime, replaced a 19th-century chapel that had geographically faced off with, and lost to, the Widener Library with the hopefully more impressive and architecturally aggressive neocolonial Memorial Church.

In White Elephants on Campus, architectural historian Margaret M. Grubiak examines the changing role of religion within certain elite American universities and colleges and concludes that because these institutions’ core missions and identities are no longer religious, their magnificent chapels and other religiously informed structures have become white elephants. They were built to ensure that religion would remain central to the university’s mission, and the project failed. The buildings are now irrelevant, financially burdensome, and outdated in design and purpose. Harvard’s Memorial Church, for instance, can “be conceived as a desiccated symbol.”

Today when university presidents are asked about the mission of their institutions, many say something to the effect of “producing knowledge” and “creating public servants,” both of which are wonderful but seem to have little to do with gorgeous, monumental, architecturally significant university chapels, libraries, and classroom buildings. But even if training ministers is no longer an institutional priority of historically Protestant universities, can’t the schools continue to use ecclesiastical architecture to inspire faith and convey that learning is a holy endeavor? Of course they can.