Real people’s mistakes

If you were in serious legal trouble, you’d want to know my friend Diane Helphrey. Diane is a skilled lawyer with significant experience in taking on difficult criminal cases. In addition to legal acumen, she has a magnanimous spirit—she’s loaded with empathy for those who have made costly mistakes.

The odds that readers of this magazine could access her legal services are remote. Diane is a public defense attorney who rises to her calling whenever someone from the public defender’s office stands before a judge and says, “Your honor, we do not have a lawyer for this person at this time.” Unless you’re wearing an orange jumpsuit as you read this column, or are unable to afford legal representation in your struggle with the law, Diane is beyond your reach.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Not surprisingly, she fields one question more frequently than all others: “How do you defend those people?” Her response is straightforward. “Those people are real people whose stories need to be taken seriously. I have a lot of empathy for people on the other side,” she says. “Most of the individuals I work with have lived through horrific experiences that I will never have to encounter. Chaotic and dysfunctional families. Generational addiction. Untreated mental illness. You name it. I rarely see a client from a stable, intact environment.”

The United States spends less per capita on public defense than any European nation. Most states have grossly underfunded public defense treasuries, in part because candidates running for office don’t win votes by expanding budgets to serve indigent people through court-appointed lawyers. “Meet ’em and plead ’em” is the practice in many locales. Public defenders meet with clients for the first time a few minutes before their hearing and encourage them to admit guilt. On first take, this sounds like sensible triage in an overloaded system.

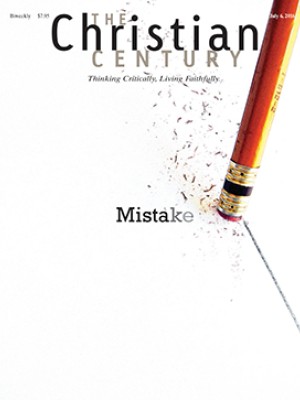

But these practices merely push people through a hasty process; they don’t provide justice, and they certainly don’t satisfy Diane. She’s grown accustomed to witnessing plenty of poor decisions, wrong choices, and deep regret in her clients. But no one leads a flawless, irreproachable life. Mistakes are made. Regrets occur. Life is what we do with our mistakes and regrets.

Diane doesn’t teach her clients to evade error; she helps them acknowledge it. As far as she’s concerned, when people acknowledge mistakes, they stop pretending. Mistakes offer greater clarity about life than any other teaching device. Robert McAfee Brown refers to mistakes as “therapeutic errors.” People who receive thoughtful support and direction from the outside have the prospect of emerging wiser and stronger from serious mistakes.

Diane is quick to add that the daily dysfunction she encounters hardly comes across as calm politeness. “It can be very depleting,” she told me recently. “But I am a hope-filled person. I always see good in other people. When I wonder if I’m making a difference, I just look at the thank-you notes. That takes a lot, you know, for disorganized people leading chaotic lives to actually sit down and write to me.” The notes are a reminding joy of her work with people who have disappointed others and themselves so deeply.