Words that count

I love this time of year, both at school and at church. It’s a season of regathering and in-gathering and joyful reconnection with friends after the summer’s adventures. It’s also a time when our communities are enlivened by people we meet for the first time. New students arrive with fresh questions and ideas, new children turn up in Sunday school, and visitors drop by hoping the church can help them find ways to be of service. In these bright fall days, new energies and hopes nearly crackle in the air.

It can also be an anxious time, because we want the quality of our invitation to our communities to match the hopeful aspirations of those who come through the door. Have we planned the right programs, chosen the right curricula? As we consider the invitation we hope to offer, it’s worth remembering the things that drew us to the life of faith, the planned and the unplanned, the organized and the accidental.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

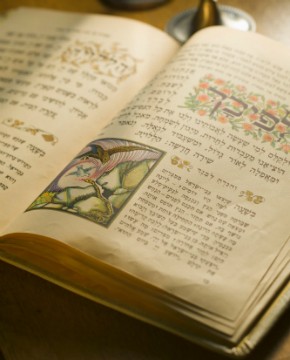

Years ago I taught a course on religious education with a gifted graduate student who recounted aspects of her Jewish education for our mostly Christian students. Her introduction to the religious life of her community included being invited by her teachers to lick honey from the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, a practice that dates back at least to the Middle Ages. This delicious invitation to the study of Hebrew linked study and sweetness forever in her imagination, as her teachers hoped it would.

My own early memories of religious education are not as auspicious. My first Sunday school teacher was my mother, and my first memories of church are of hiding and crying under the child-sized tables because I didn’t want to share her with other children. The religious education that mattered most was the one I received with my sister under the crook of our mother’s arm as she read to us. Our sacred texts were works by Dr. Seuss, Mother Goose, Ezra Jack Keats, and Maurice Sendak. The ritual of settling in together, the repeated readings of the same stories, and the proximity of our mother bathed everything she read to us in a kind of sacredness. Snuggled up together on the couch or in bed, it felt as if we had all the time in the world to roll the words on our tongues, feel their rhythms in our bodies, and discover the secrets that a well-drawn picture could hold. My mother gave me the foundation of my religious life—the feeling of having embarked on something of inexhaustible significance, something we would never finish or solve, an open-ended mystery we could seek in our books and, in Sendak’s phrase, in “the world all around.”

When my daughter was a little girl, I could never predict what invitation she would hear at church. Like my mother, I was my daughter’s first Sunday school teacher, and I always hoped that the stories and songs we shared in class would invite my kids into an exploration of life with God. But nothing I did came close to the impact of a “minute for mission” offered by a leader of our church. He began by talking about how he liked to wake up before the sun rose because he felt closest to God in the early morning stillness. The next morning, I woke at 5:30 to find my daughter awake and sitting at the window. “What are you doing?” I asked. “I’m watching for God, like John does,” she replied.

These feelings and convictions—that study is as sweet as honey, that reading is as intimate and mysterious as prayer, that we long for a glimpse of God’s presence and will wake up early to seek it—are not easy to communicate, even in church. It’s hard to find the right words to express them. But these early fall days, when our communities feel the most porous, are an opportunity to try. What matters most is our willingness to speak with each other about the things that matter most to us.

The Christian calendar gives us a saint for this work: St. Jerome, the fourth-century scholar whose translations of the Old and New Testaments formed the basis of the Latin Vulgate. September 30 is the feast day of this patron saint of translators who stands at the threshold of our rich religious inheritance and beckons us to enter. Jerome devoted his life to making scriptures first written in Hebrew and Greek available in a different language. His work of translation is our work too.

As Jerome knew, our attempts to cross the boundaries of language draw us into relationship with others—in Jerome’s case, with the rabbis who taught him to read the Hebrew text and with the women who supported his work and shared his devotion to prayer and study. His translations opened the Bible to the people of his time and place and far beyond it. And his work of translation opened him to others’ lives. This fall we have an opportunity to translate and to be translated, to find words for what matters most to us, and to be changed by the encounter with what matters to others.