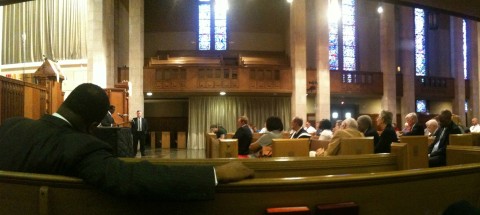

Congregational conversations

The program Scientists in Congregations, funded by the John Templeton Foundation, sought to cultivate a conversation on science and faith within congregations. About 35 congregations participated. We asked some pastors who were involved to describe their experience and what they learned.

We called our effort the Pascal Project in honor of Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), the brilliant French mathematician often considered the first thinker to seriously consider the intersection of faith with the natural sciences. First, we recruited a group of 25 people who were interested in the topic. Calling ourselves the Pascal Forum, we read several recent books and met roughly once a month for lectures, video presentations, and discussion.