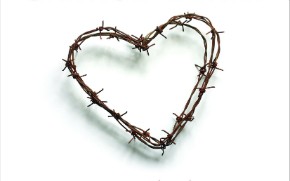

The path of forgiveness

I’ve been reading a book by Desmond Tutu and his daughter, Mpho Tutu. Desmond Tutu is the former Anglican archbishop of Cape Town. He chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was created by Nelson Mandela’s government in 1995 to help South Africans come to terms with their apartheid past.

Mpho Tutu, also an Anglican priest, is working on a doctorate in forgiveness studies. In their book, The Book of Forgiving: The Fourfold Path for Healing Ourselves and Our World, they include accounts of injustice, torture, and murder endured by blacks under the racist apartheid system, as well as amazing examples of aggrieved South Africans who decided to forgive rather than retaliate.

The Tutus criticize retributive justice and advocate instead for restorative justice. Retributive justice, reflected in most of the world’s judicial systems, is based on the assumption that those who do harm must be punished. The Tutus insist that restorative justice is the way of Jesus because it is based on redemption, and on the assumption that no act is unforgivable, no person unredeemable.