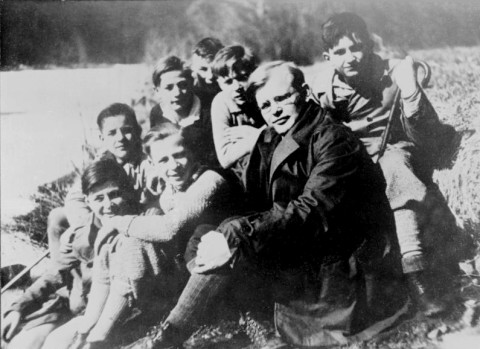

Young life together: Bonhoeffer as youth minister

I would bet that nearly all pastors who work with youth have caught themselves—just a little bit—contemplating murder. The frustration, confusion, and pure annoyance of teaching the tradition to energy drink–fueled young people can be acute. Possibly to avoid arrest and the shame and notoriety that come with a public trial, pastors often opt out of youth ministry, giving that work to someone else. Youth ministry seems to be for those wired to be enthusiastic entertainers or unyielding prison guards, or something other than the theologically thoughtful person that pastors usually imagine themselves to be.

I would also bet, however, that these same theologically thoughtful pastors have at least one book by Dietrich Bonhoeffer on the shelf and remember from seminary days at least parts of Bonhoeffer’s biography. They remember Bonhoeffer’s encounter with the black church in Harlem, his work in the Confessing Church in Germany, his writing of The Cost of Discipleship, his heading up the illegal seminary in Finkenwalde, his Ethics, and of course his arrest, his letters and papers from prison, and finally his martyrdom. Bonhoeffer is just the kind of engaged, intellectual, and action-oriented Christian that pastors admire.

These two seemingly disconnected parts of pastoral life come together in the fact that Bonhoeffer himself was a youth worker. Nearly all the direct ministry that Bonhoeffer did was with children or youth. From 1925 to 1939, when World War II broke out, it is nearly impossible to find a period that Bonhoeffer was not working with children or teens. This history is often missed when telling the story of Bonhoeffer. He saw it as his core theological and pastoral task to wade into the chaos of the lives and experience of young people as a witness to the gospel.