Glory days? The myth of the mainline

You know the story: America’s mighty mainline Protestant churches once stretched from sea to shining sea, embracing the vast majority of American people who worshiped week after week, filling glorious churches with their hymns of praise. But, alas, they are now reduced to a handful of aging folks who can scarcely pay to keep the church furnace running. In a few weeks they’ll all be gone.

Martin Marty has written that the story of “mainline decline” is so hackneyed by now that we should just reduce it to one word—mainlinedecline. It is a narrative that has dominated the interpretation of church life in America’s older Protestant denominations since 1972, when Dean M. Kelley wrote Why Conservative Churches Are Growing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But it may have a seriously faulty presupposition. We need to ask just how mighty were the older, non-Catholic and non-Orthodox Christian churches in the early 20th century. Kelley’s statistics for earlier periods were based on Edwin Scott Gaustad’s Historical Atlas of Religion in America. Kelley used these figures to show that the older Protestant churches had grown proportionately with the U.S. population up to 1960. His statistics for the period 1960–1970, in which he saw the beginnings of a decline in membership in what he called “ecumenical” churches, were based on the Yearbook(s) of American Churches prepared by the National Council of Churches, where he served.

Kelley’s perception of the beginnings of decline in oldline church membership was undoubtedly on target. Although his conclusions were met with consternation when they came out, few scholars have had their earlier scholarly work as vindicated as Kelley did.

But even if Kelley’s statistics about decline in oldline church membership have proven true, many questions remain about the presupposition that the “ecumenical” or “mainline” Protestant churches were once—perhaps early in the 20th century—the very heart of American religion.

Kelley himself did not use the term mainline churches, referring instead to ecumenical churches represented in the NCC, though “mainline” has become the label overwhelmingly used in the discussion. Apart from debatable tags, the cluster of churches that Kelley described as “ecumenical churches” can be defined as sharing some readily identifiable historic traits:

- history as a religious movement or denomination that reaches back to the colonial period or at least the early 1800s;

- inheritance of older Western liturgical patterns from the age of the Reformations;

- postmillennial beliefs that fueled progressive efforts for the improvement of society in the late 1800s and early 1900s;

- active engagement with the 20th-century ecumenical and liturgical movements; and

- active engagement with the civil rights movement in the 1960s and beyond and the feminist movement in the 1970s and beyond.

These churches include Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregational, Lutheran, Episcopal, Disciples of Christ, and some Baptist denominations (e.g., the American Baptist Churches), along with unions of these traditions, such as the United Church of Christ, in the 20th century. Although historically black churches have not been counted in the past as mainline churches, some of them share all of these traits.

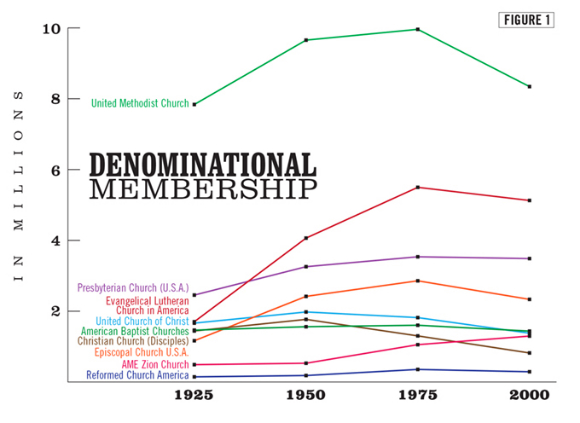

The Association of Religion Data Archives, based at the University of Pennsylvania, offers statistics on most U.S. denominational groups going back to 1925. These membership statistics paint a very different picture of American denominational life than the one often presumed in the standard narrative of decline, for they call into question Kelley’s claim that the oldline denominations grew proportionally with the U.S. population through the 1950s or 1960s.

Suppose we take the U.S. membership of the following denominations as representative of the oldline groups whose decline or demise has been described:

- African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

- American Baptist Churches

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

- Episcopal Church (in the U.S.A.)

- Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)

- Reformed Church in America

- United Church of Christ

- United Methodist Church

Then let’s examine their U.S. church membership figures, according to the ARDA data, at 25-year intervals—1925, 1950, 1975, and 2000.

Most of these contemporary oldline denominations had a complex history of unions through the 20th century. The United Methodist Church can be found under that name in 1975 and 2000, but for 1950 figures one has to add together the membership of two predecessor denominations, the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren Church. And back in 1925 these two denominations were represented by five distinct groups: the Evangelical Association, the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and the Methodist Protestant Church.

The arithmetic is even more interesting for Lutherans, who seem to have had a separate Evangelical Lutheran synod on every other street corner in Minneapolis in 1925. I count nine groups as making up the 1925 predecessors of today’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. (The mainline churches are dividing today, but they have a long way to go to catch up with how divided their predecessors were in 1925.)

Put it all together and we end up with a chart showing the denominational membership changes using the ARDA data:

|

Perhaps this data doesn’t include all the oldline, ecumenically oriented Protestant churches. Except for the AME Zion Church, it doesn’t include historically black denominations that fit the mainline description, such as the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Perhaps there are a few others that could be included—but which ones? The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod or Wisconsin Synod Lutherans? I think it’s accurate to say that these nine groups represent a strong core of oldline churches.

The figures at 25-year intervals conceal the fact that these churches reached the peak of their membership in the mid to late 1960s. Kelley had already noted by 1972 that memberships had begun declining by that time, so the 1975 numbers were almost certainly already on the decline from higher figures that would have appeared for these churches between 1965 and 1968.

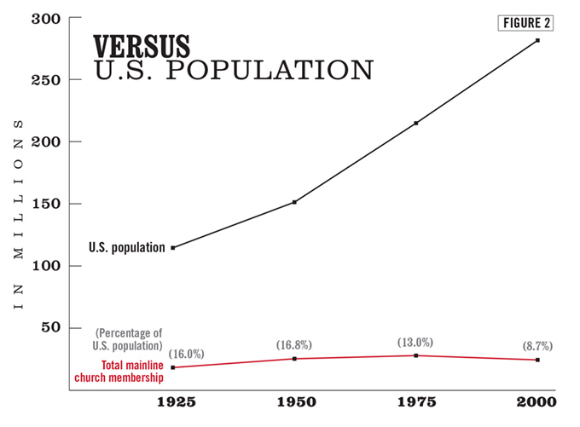

But here’s the deal: the figures given here show that these nine denominations and their predecessors never accounted for more than 16.8 percent of the population in the period for which we have statistics. This is hardly the powerhouse center of American religion depicted in standard narratives of decline. Even if you were to add some more groups and presuppose that the percentage was higher before 1925, I doubt that the membership of oldline churches ever accounted for more than a quarter of the population in the 20th century.

Figure 2 also shows that the percentage of members of these churches compared to the rapidly growing population has fallen significantly since 1950:

|

This change can be tied most consistently to trends in immigration in which non-Protestant groups constituted the great majority of newer immigrants since the late 1800s—trends that accelerated after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, as Diana Eck has shown.

So how did these churches come to be considered the mighty American mainline if they did not statistically represent anything close to a majority of Americans? That seems to be a complicated story that involves at least the following elements.

- The distant memory of a time—prior to the Civil War—when Methodists, Baptists, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians probably did constitute a majority of non-Catholic Americans, if not of Americans as a whole.

- The corresponding cultural impression that these churches were the true American churches in contrast with other Christian (Catholic and Orthodox) and Jewish groups that were still associated with immigrant communities of the early 20th century.

- The engagement of these churches in the Federal Council of Churches, the predecessor of the NCC, which was empowered by the U.S. government to allocate religious broadcasting slots for radio and television.

It’s not surprising that the term mainline would become a favored way to describe these churches, evoking the wealth and privilege of the affluent suburbs of Philadelphia that were clustered along the “main line” of railways leading west from the city.

It’s also not surprising that oldline churches would attract a substantial amount of nominal members, drawn by the sheen of mainline respectability but hardly catechized and barely if at all committed to historic Christian faith and practices. The membership figures given above do not show a consistent decline in membership between 1925 and 2000 but rather a bulge in oldline church membership that peaked in the mid to late 1960s.

It now appears that this was not a pregnant bulge; it was more like a precancerous growth constituted by a host of nominal church members now rapidly disappearing from membership statistics. To his great credit as an observer, Dean Kelley keenly recognized the problems inherent in nominal church membership, and his passionate concern through the bulk of his book was not simply to cite the statistical decline of the ecumenical churches but to name the qualitative issues that an easygoing approach to church membership posed for them.

So what’s left after the fashionable, nominal oldline church members of the mid-20th century fade away? Probably neither the mighty American mainline that never was nor the handful of wrinkled churchgoers depicted in popular reports. What remains are Christian communities with a stronger core of committed and active believers than is often represented—communities with durable institutions capable of transmitting church cultures across generations. They have considerably more members today than they had at the beginning of the 20th century, and despite emerging divisions, they have stronger forms of visible unity than their predecessors had at that time.