Hidden in Timbuktu: An Islamic legacy protected from jihadists

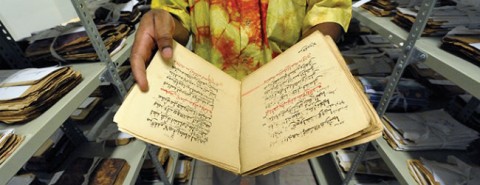

After a brutal ten-month occupation of Timbuktu, jihadists fled that city in Mali in February of this year—but not before burning all the ancient manuscripts they could find. The city’s Muslim residents have carefully guarded the old documents for centuries. These manuscripts portray an Islam that is largely curious, tolerant and interested in engaging the world, which is why the jihadists were eager to destroy them—and why residents were so eager to hide them when they got news of the impending invasion.

Located at the edge of the Sahara Desert, Timbuktu became a regional hub for the trade of salt, gold and slaves in the 13th century, as well as a center for Muslim scholarship. Intellectual inquiry often suffered at the whims of military commanders, and the city was captured and recaptured by regional kingdoms and tribal militias that were suspicious of those who sought wisdom rather than power. This was the fate of Ahmed Baba, a 16th-century scholar who wrote more than 40 books but was exiled from Timbuktu after the city was captured by a Moroccan army.

Located at the edge of the Sahara Desert, Timbuktu became a regional hub for the trade of salt, gold and slaves in the 13th century, as well as a center for Muslim scholarship. Intellectual inquiry often suffered at the whims of military commanders, and the city was captured and recaptured by regional kingdoms and tribal militias that were suspicious of those who sought wisdom rather than power. This was the fate of Ahmed Baba, a 16th-century scholar who wrote more than 40 books but was exiled from Timbuktu after the city was captured by a Moroccan army.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In the center of the city is a library named for the scholar. The architecture of the Ahmed Baba Institute uses natural air currents to keep people cool inside despite the desert heat outside. State-of-the-art labs preserve ancient manuscripts collected from throughout West Africa. Interim director Abdoulaye Cissé walked me through the document-preservation labs, where anything that the jihadists found was looted or destroyed. Then he led me down to the basement and through a dark hallway, fumbling around until he was able to unlock a door and flip on a light switch. Dozens of piles of manuscripts were carefully stacked on shelves.

“They [the jihadists] didn’t find these because the power to the building was cut off and the hallway was dark. They were apparently afraid of the dark, just as they’re afraid of the truth that’s contained in these writings,” Cissé said.

In a bold operation that is just now being made public, other valuable ancient documents, many of them privately owned, were smuggled out of Timbuktu under the jihadists’ noses. Thousands of old books and papers were packed into metal boxes and buried under piles of vegetables on trucks heading south. When residents noticed that the jihadists routinely searched all corners of buses except the space under the driver’s seat, they recruited bus drivers as clandestine couriers.

Most of the documents are now in Bamako, and Cissé and others want them back. Bamako is in the tropics, and the climate will crumble the fragile pages with mold and humidity; Timbuktu has a dry desert air that has preserved the documents for centuries. Yet Bamako residents are worried that Timbuktu isn’t secure enough. The jihadists have been forced out, but they are not far away—and they probably escaped with more than 300 technicals (Toyota Hilux pickups with heavy guns mounted on the truck beds). After a suicide bomber attacked a Timbuktu military checkpoint during renewed fighting in March, soldiers began to direct approaching men to lift their clothing and spin around in order to prove they’re not wired to explode.

The jihadists had come to Timbuktu at the behest of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, a largely Tuareg group that wants a secular and independent state in northern Mali, where the arid landscape is crossed by national boundaries that were arbitrarily drawn by Europeans. In April 2012, the NMLA and its jihadist allies took advantage of political confusion in Bamako and seized Timbuktu and other northern cities. Soon the jihadist groups, including Ansar Dine as well as the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, turned the tables on their hosts and kicked the Tuaregs out, then immediately imposed a strict interpretation of shari‘a law in the areas they controlled. Women had to be covered in public. Men were ordered to cut their pants short and let their beards grow long. Cigarettes and music were banned and schools initially closed. And the jihadists, all Sunni Muslims, destroyed many of the local tombs of Sufi Muslim saints.

The jihadists remained in control of northern Mali until January, then became ambitious and started moving south toward Bamako. They were undeterred by both Mali’s army and a regional military force that was put together to counteract them. But then the French, Mali’s former colonial masters, came to the rescue and drove the jihadists back north into the Sahara and liberated Timbuktu. They were welcomed as conquering heroes.

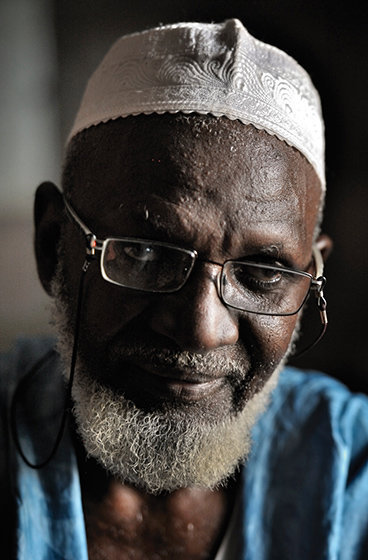

“When the French came to Timbuktu it was like the second coming of Jesus Christ,” said Abdrahamane Ben Essayouti, chief imam of the fabled desert city.

“When the French came to Timbuktu it was like the second coming of Jesus Christ,” said Abdrahamane Ben Essayouti, chief imam of the fabled desert city.

The French have promised to soon draw their 4,000 troops down to 1,000 as Malian soldiers and troops from a United Nations peacekeeping force take over. But that’s an ambitious timeline. France still maintains a major air base at Gao and continues its operations against the Islamists throughout northern Mali, aided by intelligence from United States military drones based in neighboring Niger.

Critics decry the French involvement as a new form of neocolonialism; they say the only way to really undermine Islamic extremists in the region is to empower civil society and encourage grassroots efforts, particularly among Muslim leaders. Although many agree with this view, African solutions to African problems have so far proved insufficient in countering well-funded jihadist aggression. Malian journalist Chahana Takiou told a June conference of activists in Algiers that the French intervention remains popular in Mali. “African solutions are not viable right now,” he said. “We have no other option but to turn toward the colonizer. And this hurts.”

More than half a million Malians fled their homes when the jihadists took over, one-third of them ending up as refugees in Mauritania and other neighboring countries. Those who’ve stayed in Mali present aid groups with a fascinating problem—they refuse to group themselves into large camps. Instead, in a country where hospitality has a long tradition and where people’s roots are in nomadic culture, the displaced sought out family and friends in the south and were welcomed by them.

“Since we arrived in Bamako, we’ve lacked nothing. There hasn’t been one day that any of the displaced has been hungry or sick and not received help. And that help comes from all the people here, no matter if they are Muslim or Christian. Everyone comes to help, bringing food, clothes and beds. This hospitality broke our hearts and makes us happy,” said Moha Ag Oyahitt, a Baptist pastor from Timbuktu. We talked in a crowded Bamako house shared by several families.

“Even people who didn’t have anything to share would come to show how happy they were to see us. All the Muslim organizations came to show their hospitality, bringing things to help us,” he said.

Because of this hospitality, only a handful of camps took shape. Aid agencies, which for logistical reasons prefer the centralized camps to the dispersal of displaced families, were left scrambling to meet people’s needs. And over the last year, as unmet needs have mounted and assets have dwindled, the burden on host families has in some cases grown intolerable.

Pressure is mounting for the displaced to return home. They keep close watch on the situation in the north and communicate by phone with neighbors they’ve left behind. Many would like to return before the new school year starts this month, but they’re waiting to see if the political situation stabilizes after Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta’s election as president in an August runoff election. Most government offices in Timbuktu remain closed, and the city’s banks are shuttered. Teachers at the few government schools that have reopened are paid by check, but they often have to cash their checks by sending them with a bus driver to some other city. By the time the money arrives back in Timbuktu, several people have taken a cut.

Before the invasion, Christians made up about 1 percent of Timbuktu’s population. They had grown accustomed to the occasional Tuareg rebellion, but when the jihadists arrived it was different. The Christians fled.

“We’ve had the separatists fighting for years in the north of Mali, and that was never a problem for us until they united with the terrorists. Then we started to have problems,” Oyahitt said. “We Christians lived as brothers and sisters with the Muslims. The only difference was Jesus Christ and Muhammad. Whatever we do, we invite them, and they invite us when they have births or marriages. Whatever the activity, we invite each other. When we Christians have evangelical campaigns, they come. I cannot explain to you how wonderful it was to live together in peace.”

Imam Essayouti says the jihadist groups aren’t what they claim to be.

“This city is 99 percent Muslim, but all of us are tolerant. We preach tolerance. Islam teaches us to respect all religions,” he said. “The jihadists are not Muslims, they are terrorists. They came here just to destroy and to steal. In Timbuktu we know Islam and we teach Islam, and what they think is something completely different.”

Mali debuted at number seven on the 2013 World Watch List, a publication of Open Doors, an international organization that tracks persecution of Christians. Mali had not even been ranked in previous years. What’s inexact about such information is that the jihadists here persecuted everyone, not just Christians. But extremists of all sorts revel in a narrative that puts Christians and Muslims at each other’s throats, especially in a place like the north of Africa where several cultural currents collide. Like other parts of the Sahel, Timbuktu and the rest of Mali’s north has for centuries been plagued by myriad ethnic and tribal rivalries and conflicts over land. Desertification exacerbates these troubles. The current crisis is built on those foundations. When political chaos and corruption in Bamako peaked in early 2012, the international jihadist movement—flush with fighters and weapons from Libya—realized that the time was ripe. Local conflicts opened the door to regional protagonists, but those local conflicts did not include religion to any significant degree.

Similar dynamics are at play in the military intervention by France and the United States, both of which have interest in rumored reserves of oil and uranium as well as in edging out China, which is challenging traditional colonial powers throughout Africa for economic dominance. In June, Beijing announced that for the first time it would send combat troops to participate in a UN peacekeeping mission—in Mali.

In the wake of the French intervention, many parents in Mali named their children Hollande in honor of President François Hollande. Yet the future of such enthusiasm for the French will depend on whether France can develop an effective exit strategy. Otherwise cynicism about its real motives will grow.

Similar questions are raised about the jihadists, who appropriated houses, vehicles and refrigerators in Timbuktu, often trucking the items off through the desert. Rather than viewing the jihadists as ardent practitioners of Islam, those who lived alongside them for ten months in Timbuktu see them as little more than an organized crime syndicate.

The Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, for example, is led by notorious smuggler Sultan Ould Baddy, who split his organization off from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb when he was snubbed as the group’s commander. Using its religious profile as a cover for criminal activity, particularly drug trafficking and possibly people trafficking, this and other jihadist groups have attempted to convert a huge swath of Africa into a sort of free-trade zone for terrorists. Many jihadists switch easily back and forth between the different groups, aligning themselves with whichever group offers the most lucrative reimbursement at the moment. It’s not religion. It’s business.

Maman Dedeou, a 22-year-old laborer, was a victim of the jihadists’ criminal network. Early in the occupation of Timbuktu a jihadist asked him to store some items looted from government offices and Dedeou did so, afraid to say no. But the jihadist left town, and when times got tough Dedeou sold part of the loot. The jihadist returned with a different group and came looking for his stuff. When he couldn’t find it he arrested Dedeou and charged him with theft. Over several weeks the jihadists extorted several thousand dollars from Dedeou’s family, supposedly to buy his freedom. When his family could no longer pay, the jihadists cut off his right hand.

Maman Dedeou, a 22-year-old laborer, was a victim of the jihadists’ criminal network. Early in the occupation of Timbuktu a jihadist asked him to store some items looted from government offices and Dedeou did so, afraid to say no. But the jihadist left town, and when times got tough Dedeou sold part of the loot. The jihadist returned with a different group and came looking for his stuff. When he couldn’t find it he arrested Dedeou and charged him with theft. Over several weeks the jihadists extorted several thousand dollars from Dedeou’s family, supposedly to buy his freedom. When his family could no longer pay, the jihadists cut off his right hand.

Today he’s staying with a friend and looking for work, but in the city’s moribund economy it’s difficult to find anything, especially for a man without a hand. Dedeou, a Muslim, remains angry about what the extremists did to his body and to his city. “If I saw a jihadist today, I’d cut his throat,” he said.