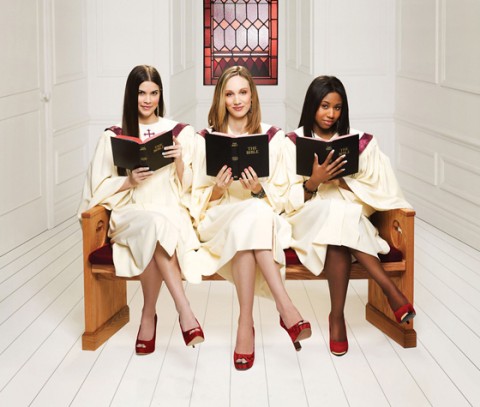

The preachers’ daughters

I wanted to hate Lifetime television’s reality show Preachers’ Daughters without reserve. I wanted to hate it for its exploitation of a cheap dichotomy: Is she a virgin or a whore? For its all-too common presumption that the point of Christianity is the policing of young women’s sexuality. For the faux Gothic font and the papering of vague religious imagery over the lives of people who stand in a particular American Protestant strand of the Christian tradition.

Unquestionably, I do hate the promotional images of the show’s three teenagers—Taylor Coleman, Kolby Koloff and Olivia Perry—for reducing complicated lives to a hunger to escape a white choir robe for a mirror, lipstick and a cell phone. (Does anyone really think that the choir robe is incompatible with lipstick? Or that access to lipstick equals freedom and prosperity?)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“Taylor is set on pushing boundaries established by her strict father . . . who . . . wants nothing more than to keep Taylor as his little angel.”

“Kolby is a fun-loving, curious 16-year-old ready to start dating, but quickly discovers it won’t be as easy as she thinks since she has not one, but two preacher parents.”

“Olivia is an 18-year-old teen mom who, after partying hard, using drugs and drinking in high school, dramatically changed her life after the birth of her daughter.”

But the reality of this reality TV show proves more complicated than the show’s scripts. All three of the daughters depicted in the show are preachers’ kids—in different locations—from the Pentecostal-charismatic spectrum. All three appear to have a serious commitment to their Christian faith and real struggles with how to live out those commitments.

The show offers plenty of cringe-inducing examples of how not to teach sexual morality. Why does Kolby’s mom hand out information on sexually transmitted diseases at a Halloween party? Why are young children present in the muddled class on sexuality that Taylor’s parents ask her to take a second time? Why does Taylor’s church suddenly outlaw kissing outside of marriage?

It’s clear that sexual purity has been the centerpiece of Christian moral education in Kolby’s household, and her older sister Teryn decides to take this on—attacking its concomitant legalism—by confessing to her sisters that she wasn’t a virgin when she married. Kolby is shocked and tearful, but one hopes she’ll eventually comprehend Teryn’s wish that her sisters learn that their lives won’t be utterly undone if they make a mistake and that their faith might be larger than they imagine.

If nothing else, Preachers’ Daughters highlights the church’s desperate need for theologically coherent teaching about sex—teaching that treats Christian sexual ethics not as a set of rules to be followed, but as a way of life that bears witness to a faithful God.

My impulse to hate the show without reserve is challenged by the humanity and defiance of all three young women. Not their defiance of their parents or the church (though, predictably, there is some of that) but their defiance of Lifetime television and the stilted scripts they have been handed.

Taylor may push boundaries, but she also leads worship, shares her personal life with adults who love her and takes on extra responsibilities when her father is sick. Kolby does want to start dating, but she doesn’t seem a bit surprised by the boundaries and rules set by her parents, and she embraces the sexual ethic that she has been taught. Olivia is not a hapless victim, chained down by her infant, but a young woman who has thought through and taken responsibility for her choices, who clearly loves her daughter and relies on her faith.

So some humanity, and with it some gospel, breaks through the show’s canned falsity. Take a montage that feels stiff and staged: Olivia worries about her baby’s health because of her alcohol consumption before she knew she was pregnant. She confesses to the pediatrician—who seems oddly fine with imparting sensitive medical information on camera—and the doctor pronounces the baby healthy.

It’s hard to imagine that this segment wasn’t carefully prearranged, but it’s nonetheless moving to hear the gospel spoken over images of the little daughter whom Olivia loves. What’s moving is not the contrived theology that God makes everything come out all right, but the obvious love that Olivia and her family have for the baby who might or might not have been all right, but who would have been loved regardless.

One aspect of the teenagers’ lives that Lifetime seems to have no script for is the one introduced by the word preacher: a religious life lived in community. While there are shots of the dads preaching, the show does almost nothing with the expectations congregations so often impose on clergy families. Church life is reduced to a few scenes of worship, an ocean baptism service and a home-based Bible study. The most we see of church comes in the segments focused on Taylor, the only one of the featured daughters who isn’t white, and the only one of the daughters portrayed as living with heavy expectations, not just from mom and dad but from the church.

Taylor, Kolby and Olivia are young, yes, and I don’t doubt that in maturity they’ll look back at their clichéd adolescent truisms with a sigh. But all refuse the script that national television has given them, taking the show’s sad attempts at provocation mostly in stride. Thanks to the show, Taylor, Kolby and Olivia now have more than 10,000 Twitter followers apiece, and they have the chance to maintain their own voices and their desire to bear witness to what God is doing in their lives.