Vengeance is mine

Near the end of Django Unchained, a freed slave named Django rides across a Mississippi plain, planning to wreak vengeance on the plantation owners holding his wife captive. All the visual symbols of a western finale are present: a lone hero set in a barren landscape, a horse worked to a lather, a gun in a holster and a cowboy hat cocked back. Salvific undertones are made explicit in the pulsating rhythms and lyrics of the accompanying song by John Legend: “I’m not afraid to do the Lord’s work / You say vengeance is his, but I’m gonna do it first.”

Perhaps Quentin Tarantino’s most controversial film yet, Django Unchained is a mashup of western, comedic, blaxploitation and rogue hero tropes. The result is an irreverent, profound and problematic exploration of America’s original sin and the power of a revenge fantasy.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

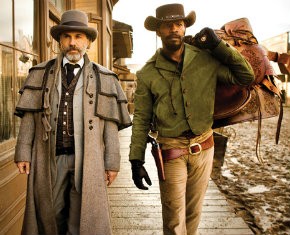

Django (Jamie Foxx) is bought and freed by a German bounty hunter, Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz), who needs Django’s help in identifying three fugitives. The three men used to be Django’s overseers. When it turns out that Django is a prodigy with a gun, the two form a partnership: Django will bounty hunt for a season with Schultz and then Schultz will help him rescue his wife, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), from the charming but sadistic Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), to whom she was sold when she and Django tried to run away from their original owners.

If Django were a white man rescuing a woman from Comanche Indians, the movie would feel like a spaghetti western updated with profanity and a hip-hop soundtrack. But Django is not white, and therein lies the (flawed) genius of Tarantino’s vision.

As in Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino rewrites history through the lens of fantasy. In this fantasy, the black ex-slave switches roles with his white mentor, taking him as a sidekick in his own quest for justice and salvation. Given that this is a Tarantino film, that salvation is soaked in the blood of enemies. Tarantino is fascinated with the style of evil—its excesses and panache. As in all his films, the villain—in this case Candie—steals every scene he’s in.

Tarantino’s fascination with evil combined with his fetish for violence creates a troubling film. The camera takes delight in the body in pain. When someone is shot, blood and gore spout with impossible ferocity and quantity. The crack of the overseer’s whip and the sizzle of his branding iron on flesh are amplified for maximum effect. The aesthetic pleasure of the camera work is seductive but deeply unsettling. Tarantino seems to care more about breaking taboos and pushing stylistic limits than examining the evils of slavery.

Yet Django’s vengeance reminds me of hellfire sermons in which the terror of God is the mirror image of God’s grace. A good hellfire sermon, like Jonathan Edwards’s “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” is meant to awaken a sense of God’s ultimate justice and the abyss of human sin. The most striking image in such preaching is not of the torments that await the reprobate but the justice with which they will suffer. God is often imagined as smiling, even laughing, at the just destruction of the wicked.

As Django brings his final judgment on the plantation, he turns and grins at Broomhilda, who claps her hands jubilantly. It is impossible not to join in their exhilaration at the notion that evil could be categorically cast out of the world.

In hellfire sermons and film fantasies, a desire for revenge can easily morph into an overconfident projection of God’s justice. It should strain the Christian imagination to place Django in the role of God, confidently delivering the final judgment. But in that image there is also a word of truth about the depths of sin.

The point of a hellfire sermon could be twofold: to resist an overly confident assumption that we stand on the side of the redeemed and to offer the promise that God’s justice does not sleep. When it comes to the horrors of institutional slavery and our propensity to distance ourselves from historical evil through fiction, Tarantino’s fantasy serves a similar role.

In most historical narratives about the horrors of slavery, white men (and sometimes women) are shown as key agents in the institution’s demise. The presence of such characters allows contemporary white viewers to hope that, had they lived in such a time, they too might have stood on the side of justice.

There is no such character in Django Unchained. Django does not need his white partner, who hinders more than helps his pursuit of freedom.

Tarantino’s vision does not pretend to be historically accurate, but by making Django the agent of justice, the fantasy more firmly rejects the evils of slavery than many more historically accurate accounts.

Django’s vengeance is swift and complete: a resounding word of condemnation and judgment on a sinful structure that must be utterly destroyed in order for him to fully claim his humanity. This vision of vengeance is morally problematic, but it contains a kernel of gospel truth: sometimes there is mercy, and even joy, in the fantasy that evil will meet an irrevocable end.