The liberal agony: Why there was no new New Deal

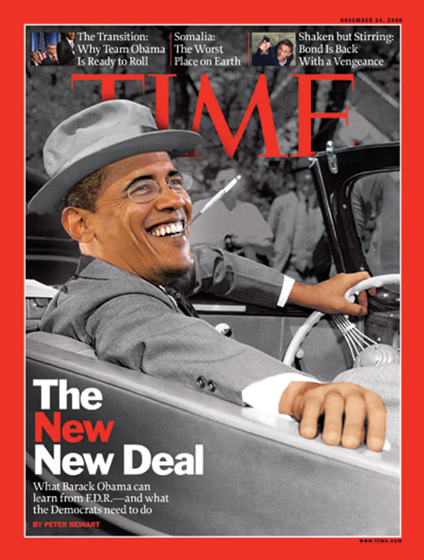

Shortly after the election of Barack Obama to the presidency in 2008, the cover of Time magazine featured a fabrication of an iconic photograph of Franklin Roosevelt, cigarette holder at a rakish tilt, sitting at the wheel of a convertible. FDR's face and hands had been displaced by those of Obama's above a headline speculating on the arrival of a "New New Deal." That same week, the New Yorker featured an article by George Packer advancing a similar speculation, which was illustrated with a drawing of much the same invention.

What this image in two major American magazines mani-fested was the hope on the left and the fear on the right that Obama would revitalize and extend the New Deal order that had been significantly dismantled by the conservative ascendancy since the mid-1970s (and that "new Democrat" Bill Clinton did little if anything to stem in his eight years in office).

In the Time cover story, young liberal intellectual Peter Beinart burbled that "the coalition that carried Obama to victory is every bit as sturdy as America's last two dominant political coalitions: the ones that elected Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan." He predicted that "taking aggressive action to stimulate the economy, regulate the financial industry and shore up the American welfare state won't divide his political coalition; it will divide the other side." Packer saw the Obama victory as the promise that "for the first time since the Johnson Administration, the idea that government should take bold action to create equal opportunity for all citizens doesn't have to explain itself in a defensive mumble."

In the Time cover story, young liberal intellectual Peter Beinart burbled that "the coalition that carried Obama to victory is every bit as sturdy as America's last two dominant political coalitions: the ones that elected Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan." He predicted that "taking aggressive action to stimulate the economy, regulate the financial industry and shore up the American welfare state won't divide his political coalition; it will divide the other side." Packer saw the Obama victory as the promise that "for the first time since the Johnson Administration, the idea that government should take bold action to create equal opportunity for all citizens doesn't have to explain itself in a defensive mumble."