Many nights during the season of Advent, my family and I turn off nearly all the lights in the house. We gather around a makeshift wreath, a metal bin decorated with stars and berries and filled with plastic greens, all courtesy of Michaels craft store. We sing the first verse of “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” while lighting the appropriate number of candles. We share “sads, glads, and mads,” and, at the end, one of the children leads us in a repeat-after-me prayer. I look at their faces across the flickering candlelight as they press into our laps and hug us close. This idyllic scene is often punctuated with shouts and arguments over who’s next, who will blow out which candle, and then a rush to finish the ritual so we can send everyone to bed.

I love Advent. I need the visceral reminder of what we’re anticipating: that the Word came to inhabit the same world we do, the same bones and marrow, the same air. Advent comes around every year, and despite the frenetic and frantic tones of the season, it’s this that gets me in the end. Even if I haven’t been paying attention when the candles are lit, whether it’s peace or hope or joy that week—it’s the story of “God moving into the neighborhood” (The Message), God choosing to come near, God choosing the fragile and ordinary that always knocks the breath out of me.

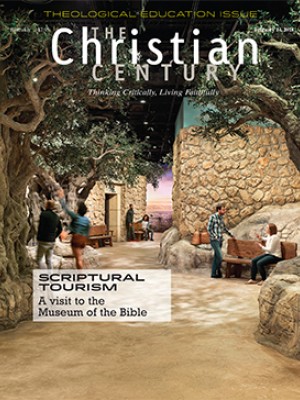

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The season of Lent effects a similar sensation in me—that is, wonder at God’s entrance into the world in a particular way, in vulnerability and humanity. But we are in the Gospel of John, which presents a high Christology and emphasizes the divinity of Jesus the Christ. After the wedding at Cana (2:1–12), we come to John’s version of Jesus toppling the temple. This is significantly earlier than in the synoptic Gospels, where Jesus turns the tables at the end of his ministry, an event that arguably becomes the impetus for the religious leaders to seek his arrest. In John, it’s paired instead with his first miracle, the first sign: turning water into wine.

The Gospel of John is sometimes referred to as the Book of Signs, and the narrative is framed around these signs—changing water into wine, healing the royal official’s son, healing the paralytic, feeding the 5,000, walking on water, healing the blind man, and raising Lazarus. The signs aren’t just miracles. They invite us to see and explore the meaning of Jesus as both the son of man, with all his sads, glads, and mads, and the son of God, who inspires celebration and instigates confrontation. It’s these signs that guide us in our journeys, whether through Advent or Lent, whether to Bethlehem or to Jerusalem or to Emmaus, as we discover the presence of God as Emmanuel, God-with-Us.

The word made flesh is the beautiful sign of incarnation, but it is a proclamation of something more. It is the miraculous disruption of the status quo, which Jesus speaks of when he shouts, “Stop making my Father’s house a marketplace!” He doesn’t just criticize the dishonest and shady practices of vendors selling the necessary wares for appropriate temple worship. He announces that he is there to take down the entire structure.

“Destroy this temple,” Jesus says to the leaders who ask him for a sign, “and in three days I will raise it up.” In John’s Gospel Jesus isn’t talking about changing the policies around who sells what when. This isn’t about reforming temple practices. He wants to turn over tables, yes, but also to turn over the very pillars of existence through his very existence. Later when Jesus encounters the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:1–30), he says to her, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem.” The hearers of this Gospel would have that scandalous image in front of them already—the rubble and wreckage of their temple. As this week’s passage concludes, after the resurrection the disciples remembered Jesus’ words about the temple, “and they believed the scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.”

Jesus came to replace it all with himself. He says it, clearly and succinctly, several times throughout John’s Gospel. I am the bread of life. I am the light of the world. I am the good shepherd, the true vine, the door. I am the way, the truth, and the life. I am the resurrection. I am here.

And so it is significant, though it may seem strange and foolish to the rest of the world, that whenever we gather together, whether it’s around the Word or words, candles or ashes, whether bread and the cup or fake plastic greens, we proclaim that God is here. God with us. Whenever we invoke this promise at the table—communion or kitchen—even if it’s simply, “I am mad,” “I am sad,” or “I am glad,” we invoke the ways Jesus said, “I am,” too, and the ways he shares in our humanity, in our weakness and need. But in coming to us, he changed it all, so we never say these words in isolation—no matter where we are, and even if the darkness presses in on us.