The people still gathering at 38th and Chicago

“Stop giving us a reason to still be out here,” says George Floyd Square protest leader Marcia Howard. ”Give me a reason to go in the house!”

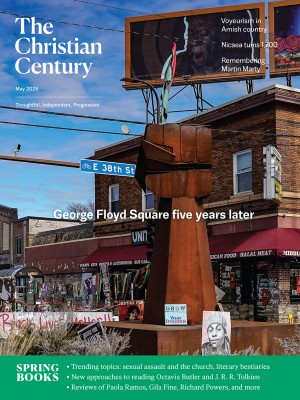

Activist Marcia Howard at the People’s Way in George Floyd Square (Photo by KingDemetrius Pendleton)

Read Elizabeth Palmer's story, Still seeking justice for George Floyd, about how George Floyd Square in Minneapolis remains a site of protest, lament, and mutual aid.

Marcia Howard is an activist, educator, and union leader in Minneapolis. She lives in George Floyd Square and leads protests there. Howard talked with the century about the movement that has persisted at the corner of 38th and Chicago since Floyd’s murder and how it fits into the larger story of the United States.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

How did you become an activist in George Floyd Square?

When all of this started, my life was good. I was traveling all over the world; I cooked all the time; I made yeast from scratch. I used to say, “My name is Marcia Howard; they call me Marcia Stewart,” because that’s all my Instagram was about: food and vintage clothes.

How do you radicalize a 47-year-old high school English teacher? You kill a Black man 263 steps from her front door while a student of hers films it, and then you have the audacity to say that he died of a medical emergency. No.

So I came outside, and I stayed outside. Three days after they killed George Floyd, I told my students, “You all pass; you all get credit.” He died—he was slain—on May 25, and I did not go back to work then or for the next year.

How did the neighborhood change after his murder?

In the early days, there was a 24-hour occupation by the protesters, with barricades up and armed resistance. Police and city officials weren’t allowed in. We had to negotiate getting mail in. We had our own medics, who provided glucose monitoring and gave out insulin. The city forcibly opened the streets back up to traffic on June 3, 2021. But there’s a provision that says public art can’t be moved, so we replaced the barricades with the Black power fists the next day.

How did the meetings at the former gas station come about?

We started holding daily meetings at the suggestion of a neighbor, Julia Eagles. We basically had an autonomous city behind the barricades, and we wanted to make sure that it was safe, sanitary, secure, and sacred. The volunteers would meet every 12 hours to coordinate. We met in the middle of the street, so we called it Meet on the Street.

One day it was raining, so we asked the manager of the Speedway if we could meet under the canopy in the parking lot. He said sure, and then we just kept meeting there. When the store shut down, we continued to meet under the canopy. That’s how the Speedway became the People’s Way.

What are the future plans for that space?

The city owns it, and they’ve posed the idea of selling us the land for $1. But there’s a reason the US is dotted with defunct, derelict gas stations: they’re basically superfund sites. The cost of the property is one thing; the cost of abating the toxic oil is another.

But we’re not here for the land. They asked us in August 2020, Why are you still here? We said, for justice. Well, what does justice look like? So we went up and down these streets, asking the homeowners and the people in the businesses and the brothers in the hood: What do you want, what do you need—not just to live, but to thrive? And those answers became the 24 demands we presented to the mayor, the commissioner, and the governor. None of those demands includes owning a building.

It’s been nearly five years, and you’re still meeting twice each day. What keeps these meetings going?

We’re neighbors. We have committed to showing up for our community, for the 24 demands. And our consistency confounds the powers that be. They thought in May, OK, they’ll be done by August, and then they thought in August, OK, they’ll be done when the first snow flies, and then they thought, Surely they’ll be done when it gets below zero. Then they killed Daunte Wright, and then they killed Dolal Idd, and I was like, “Stop giving us a reason to still be out here! Give me a reason to go in the house!”

At 38th and Chicago, we listen to Black and Indigenous women first, because we’ve tried it every other way. And that’s why we’re consistent: we understand that this is the way we are going to get out of the old mode of life, of patriarchy and of White supremacy.

I’m not religious, but you’ll notice that there is a religiosity to the meetings: the consistency, the gathering together, the call and response. That religious aspect is so visible that a few years ago someone referred to “Marcia Howard and her cult.” If it were a cult, I wouldn’t be schlepping wood in the morning to build the fire!

Why do you think there aren’t more people devoted to the movement for Black and Indigenous lives?

We all know what this colony, this business venture, was founded on: a mescla, a mixture, a band of disparate Europeans who needed to feel some cohesion and unity. They needed something to be juxtaposed against. They accomplished this through race—a new concept at the time—religion, and capitalism. Capitalism in this country started with the transatlantic slave trade, which wasn’t regular trade. Think about it: they were willing to trade humans. We were the capital.

Whiteness doesn’t exist without Blackness. Frankly, neither does Christianity, not in the way it’s been interpreted from the 1500s on. It just doesn’t. When I teach William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and we read “The Little Black Boy,” sometimes I challenge my students of European descent: Do y’all ever think about the game that’s being run on you? Can you see this paucity of theory, the paucity of this premise? I love the Christian Bible, but if I’ve gotta be on my knees for somebody else to feel tall—child of Ham though I am—that’s just sad.

What would you say to a White neighbor or student who started thinking about systemic racism after George Floyd’s death but then got stuck in feelings of guilt or hopelessness?

We all get played. But White guilt serves no one. That doesn’t mean you get to be smug, and it doesn’t mean I’m giving you absolution. I’m saying let’s stop clouding ourselves with this fucking emotion, because that’s just propaganda. I need us to be clear-eyed so we can actually fix this city. I plan on dragging the city of Minneapolis into the redemption that I know we are capable of. I’ve lived here for 30 years, and I am so proud of my adopted city. I’m proud of the people that I meet. But I’ve also seen that “Minnesota nice” get corrupted, manipulated, and chucked out the window. I want it back. Make America great again; make Minneapolis the way that I know it can be.

What are the biggest barriers to this redemption?

Racism under White supremacy is a theology, a religiosity. It requires the consecration of the land with Black, Brown, and Indigenous blood—our bloodletting is what assures Whiteness that all is well. We have to—and I say we, because I’m under White supremacy, too—we have to be able to spill the blood of people of color, ritualistically. Then we can sigh again and feel okay.

You may not think that that’s how you feel, and yet, we’re in a coffee shop and you’re not thinking about Robert Brooks, or Daevon Saint-Germaine, or the three Black people who were just killed under no-knock warrants. Their blood has been shed, and we think of it with the same amount of concern as when we’re driving and we see a smushed animal. We might check to see—was it a racoon? A squirrel? A skunk? And our noses crinkle a little bit, and we keep driving. It’s the price of progress; it is what must be for us to have what we have.

Is it my brother? My father? Me? She wasn’t the person the warrant was for; he didn’t have a gun. But all is well, because this country has been founded on peasants who became aristocrats as soon as they got here, who gained the ability to take lives—who became the crown, the colonist, the conquistador—as soon as they arrived.

But we’re a young nation—only 250 years old. I don’t know what’s coming after this. I think it will be fascinating, because European-descendant people will have to divest themselves from Whiteness. Whatever that looks like, it has to happen.

What’s your vision for George Floyd Square?

My vision is: Stop killing Black people. The 24 demands; that’s my vision. When I say, “No justice, no streets,” I’m saying, “Y’all not gettin’ these streets back until you give us somethin’ that looks like justice!” I’m protesting until the demands are met. When they fulfill them, I’m taking my Black ass home.