Still seeking justice for George Floyd

Five years after an infamous murder, George Floyd Square in Minneapolis remains a site of protest, lament, and mutual aid.

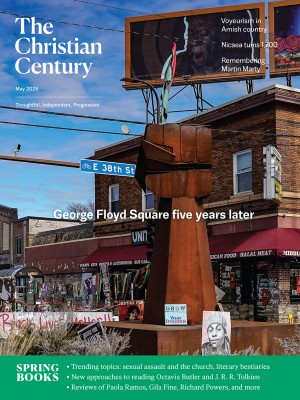

George Floyd Memorial Square in Minneapolis (Photo by KingDemetrius Pendleton)

It’s 19 degrees below zero, and I’m standing with Marcia Howard in the parking lot of a former gas station across the street from the corner store where George Floyd was killed. Howard is a high school English teacher who lives about a block away.

“I meant to come early to start the fire,” she says, “but the moment I stepped outside, I had an asthma attack. I had to go back in and let my lungs warm up.” She glances at the fire pit, which sits in the middle of a circle of benches between the old gas pumps. “It’s too cold to stay out here without a fire. Let’s go to the coffee shop.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We walk across the icy parking lot to Bichota, the coffee shop. Joining a few others who have gathered, Howard begins the neighborhood protesters’ morning meeting. They have been meeting twice a day since May 2020, when Floyd was murdered by a police officer and their Minneapolis neighborhood became the center of a global resistance movement.

They begin by discussing a protest held the previous day. Someone asks about the status of the local charter commission’s plan to cut city council members’ positions to half time. Someone else tells a funny story about a TV show. Then the conversation turns to the history of redlining in suburban Apple Valley.

We’re sitting at a large table next to a picture window. Across the street, we can see the memorial site where pilgrims come from all over the world to pay their respects and leave their tributes—mementos, notes, and handmade art—at the exact spot where Floyd lay pinned to the pavement for nine minutes and 29 seconds while the officer choked the life out of him as bystanders watched in horror. Five years later, the communal trauma is still palpable in the area that’s now called George Floyd Memorial Square. But there are also signs of resistance everywhere, artifacts that tell a story of people coming together after violence to lament and to protest, a community rebuilding itself through art, activism, and mutual aid.

Nowhere is that resistance more apparent than among the group of neighbors who have gathered in the gas station lot at 8 a.m. and 7 p.m. each day for the past five years. They meet to organize, debrief, strategize, and share stories. When it’s cold they build a fire; when it’s very cold they might move into Bichota. At every meeting, someone takes a picture and posts it on social media, as if to say, Look: we’re still here. We will be here until justice has been achieved. Their goal is to rebuild a neighborhood and take down White supremacy.

George Floyd Memorial Square consists of the four square blocks surrounding the memorial site. A large wooden sculpture of the Black power fist stands in the middle of each of the four intersections leading into the Square. They were modeled after a larger fist that stands in the central intersection, cast in iron by sculptor Jordan Powell-Karis and installed by activists during the night. The memorial area, on the pavement outside the front door of what was Cup Foods in 2020—it’s since been renamed Unity Foods—is cordoned off by ropes and concrete barricades. In the summer, planters filled with flowers form a border around the memorial. Over the winter, they’re stored in a greenhouse just north of the memorial site. There’s a fire arts studio next to the store that donates electricity to the greenhouse.

Across the street, at the former gas station, what was once a Speedway sign now says People’s Way. The parking lot hosts the activists’ gathering space, the People’s Closet filled with free clothing, a community lending library, informational boards, and a marquee sign proclaiming “people over property.” The boarded-up building is painted with a mural honoring neighbors who died too soon. Large plywood boards leaning against the building display the 24 demands compiled by local residents in 2020 and presented to the city.

Each of these elements embodies a story. The fist sculptures mark a neighborhood that was quickly beset by so many mourners and protesters that they had to put up barricades. For a year, only local vehicle traffic was allowed through. No tourists, no transit, no police. And there were no riots, fires, or arrests. Volunteer guards monitored the barricades day and night to keep the neighborhood safe. Other neighbors volunteered to tend the spaces where mourners left gifts. They watered the flowers and swept the sidewalks. When a handmade sign got soggy from the snow, the caretakers would gently remove it and send it off-site for preservation by volunteers.

The People’s Way tells of free meals, anti-state fairs, musical celebrations, rallies, homegoing services, and shared resources. It tells the story of a volunteer ambulance service with the phone number 612-M*A*S*H* (Minneapolis All Shall Heal) and of a medical tent that became a bus that became a shed that became a clinic. It tells of an autonomous protest zone that for a whole year—until the city forcibly removed the barricades—showed the nation what it looks like when community members commit to taking care of one another.

The 24 demands tell their own story. Some are specific, such as “Release the death certificate of Dameon Chambers” and “Invest $400,000 into the George Floyd Square (GFS) Zone through the neighborhood associations to create new jobs for young people.” Others are more sweeping: “Require law enforcement officers to maintain private, professional liability insurance” and “End qualified immunity.” All of them aim to address problems that were woven into the fabric of the neighborhood long before Floyd stopped for cigarettes that day. To date, 12 of the demands have been met.

The artwork in the square tells the story of Floyd’s murder as just one piece of a much larger story. Just north of the greenhouse is the Mourning Passage, a long list of names of people killed by police that stretches across Chicago Avenue. Created by art educator Mari Mansfield, it gets repainted by volunteers each year after being worn down by traffic and weather. There are murals everywhere—on sidewalks, buildings, and fences. There are pictures of George Floyd but also of Angela Davis, Marcus Garvey, Frank Yellow, Murphy Ranks, and dozens of others.

A few doors down from Bichota is KingDemetrius Pendleton’s photography studio. Its front door is plastered with photos of people killed by police: Amir Locke, Cordale Handy, Chiasher Fong Vue, Philando Castile. When I talk with Pendleton at his studio, he speaks admiringly about Darnella Frazier, the teenager who posted the video that made Floyd famous. She kept the camera’s focus on the police officer, he tells me. She was determined to record every emotion on that officer’s face, to capture each time he shifted his body weight to put more pressure on the knee that was pressing Floyd’s neck to the ground. Pendleton attributes the officer’s murder conviction mostly to Frazier’s unwavering focus on him throughout those excruciating minutes. But she had no intention of creating a viral video that evening, he tells me; she was just taking her nine-year-old cousin to the store for snacks.

A block northwest of Pendleton’s studio, just outside the square, is the Say Their Names Cemetery, an art installation designed by Anna Barber and Connor Wright. Rows of corrugated plastic tombstones spread across a drainage field for an entire city block, each one inscribed with the name of a Black American who was violently killed. Emmett Till, Sonya Massey, Aiyana Jones, Laquan McDonald. To the north, a massive weeping willow stands guard over the grave markers. The wooden fence at the south end of the graveyard displays an Anishinaabe flag, a medicine wheel, colorful banners about Native history, and a call to remember the “500,000 missing boarding school children.”

Howard tells me that the square sits at the intersection of four different neighborhoods, each with its own racial and economic makeup. Norwegians came in the 1800s seeking free farmland; they displaced the Anishinaabe people. Once Howard had her house appraised twice in the same month: the first time with photos of her Black family members covering the living room wall and then again without them. The second appraisal came in $60,000 higher. She wants me to understand that our present-day concerns about the racial dimensions of property values, infrastructure investments, and gentrification rest on an earlier story of genocide and stolen land.

Howard finds Minneapolis fascinating because it has so many Scandinavians. The Lutherans, she says, are known for being extremely generous. They welcomed refugees from various ethnic groups: Hmong, Karen, Somali. But then, in the early 2000s, she observed them pulling the welcome mat back in. When she started teaching 26 years ago, her Lutheran students would frequently volunteer at neighborhood soup kitchens or the homeless shelter. These days they go on mission trips to Guatemala instead.

The turning point came when the city’s demographic change reached a certain level. Once a population exceeds 20 percent of minorities, says Howard, the majority starts to get uncomfortable. She offers the example of Beltrami County up north, where Native Americans make up about a quarter of the population—and the police kill them at a higher rate than the police kill Black people. “That’s what the majority needs: to have control over their lives. It’s blood memory, it’s sense memory, it’s epigenetics. You’ll never overtake our fort. You’ll never overtake the plantation.”

Howard and I walk a block south to Calvary Lutheran Church for a meeting of the Community Visioning Council, a group of residents and business owners who are negotiating with the city about its plans for redeveloping the square. From the outside, Calvary looks like a typical Gothic Revival church: yellow brick over limestone, slate roof, with crosses and stained-glass windows. The bell tower is adorned with a George Floyd banner. But a few years ago the church was transformed into an affordable housing complex called the Belfry Apartments. The community meeting is being held in the former sanctuary, which has the architecture of a church but a flexible interior design to allow for worship on Sundays and community use the rest of the week.

Shari Seifert, a member of the congregation, tells me how hard it was to find a developer willing to transform the church into affordable housing while also building out a dedicated space for the food shelf and preserving some of the sanctuary’s aesthetic character. She says there are 41 housing units, ranging from studios to three-bedrooms. About a third of them are set aside for chronically unhoused people. “All of the units fall into a category called deeply affordable,” she adds, “so people don’t pay more than 30 percent of their income. I know one person who pays something like $34.”

When Floyd was murdered, Calvary jumped into action as people flocked to the neighborhood to mourn, rallies and marches broke out across the city, and the area near the Third Precinct police station burned. Calvary set up folding tables and handed out water and masks. They stored food, water, diapers, and other supplies for neighbors in need. They expanded their food distribution program. In her book Ashes to Action, Seifert explains why the congregation was prepared to respond to Floyd’s death in such an immediate and robust way. They already had a race equity committee and had spent time as a congregation doing cultural competency assessment. They were active members of Sacred Solidarity, a multifaith coalition of congregational anti-racism teams. In 2017, with the help of theologian Mary Lowe, they read James Cone together. “The lynching of George Floyd one block from our church called Calvary elicited the memory and meaning of reading The Cross and the Lynching Tree,” Seifert tells me. In 2021, the congregation voted unanimously to move forward with the affordable housing project.

It’s 21 degrees above zero, and I’m in the square for a second day. I’m at Bichota to meet Angela Harrelson, George Floyd’s aunt. When she arrives and I stand to greet her, we both notice more than a dozen people gathered around a cake at the large table. Before we sit down, Harrelson introduces me to Raycurt Lemuel, who is holding a violin. He’s the cofounder of Brass Solidarity, an ensemble that plays at the People’s Way every Monday no matter the weather. He explains to us that the group he is with is holding a wedding reception for two activists. They’d gotten married less than two hours earlier, during the morning meeting. Now the brides are on their way back from filing the legal papers.

Harrelson and I sit down to talk about her nephew. He went by Perry, his middle name, and I ask if I may call him that even though I never met him. “Of course you should call him Perry,” she says, smiling and reaching across the table to grasp my hand. “That’s who he was. George was his father.” She tells me that when Perry was a child, he would come watch her cheerleading practices. He had dreams of becoming a professional athlete. He loved his mother. He never had a close relationship with his dad, who was a professional musician. Like his dad, Perry struggled with addiction as an adult. Harrelson is a mental health nurse, so she knows a lot about what addiction can do to a person. But even amid that struggle, she says, Perry was always kindhearted. He took his wheelchair-bound aunt to church and helped elderly people up and down the stairs. He had a gentle spirit.

I get the sense that Harrelson is a bit of a local celebrity. The activists milling around all call her Miss Angela or Aunt Angela and treat her with reverence. A young woman wearing a bright yellow hat bounces over to the table, hugs Harrelson, and sits next to me. She introduces herself as “Jenny with the Freckles” and says she runs the People’s Closet. She tells us she brought the veil for the wedding, no easy task with just an hour’s notice. Another activist comes over and hands us a phone displaying a picture of the brides—Ashe and C, both of them glowing. Ray plays wedding music on his violin. The brides arrive, and a few minutes later Ashe comes over to offer us cake. It’s a marble cake, its thick white frosting liberally dotted with rainbow-colored sprinkles. I ask why they chose this place to get married. “This is where our life together began,” she says, pointing to the People’s Way.

Harrelson and I walk across the street to the memorial. She shows me the exact spot where Perry was pinned to the ground, and we each pay our respects in silence. There are thousands of items that people brought—notes, drawings, candles, stuffed animals, a Bible—all covered with a thin layer of snow. Harrelson lives in a different part of Minneapolis, but she comes to the memorial most weekends so she can talk to visitors and take photographs of the artifacts they leave behind. She posts these pictures on Facebook, creating something like a virtual memorial space for those who are unable to visit the square in person.

A police car drives by, slowing down at the roundabout. It’s the first one I’ve seen in the square. “Those are the community engagement officers,” says Harrelson. “They drive by or walk by every so often.”

Then she tells me a story. “One day, I was at the memorial, and the community engagement officers were walking by. I asked them how they were doing, and they said fine. Then I introduced myself and told them that I’m George Floyd’s aunt.” I ask how they responded. “They were shocked. I told them that I wished they’d been the first ones to say hello, that I shouldn’t have had to be the one to greet them. They listened to me, and then they walked on.” She pauses for a moment. “They were polite. But I wish they’d stopped to pay their respects.”

As she’s talking, I notice the police car’s license plate. It just says “POLICE,” with no other letters or numbers. Confused, I ask Harrelson about it: “Are they all the same?” Yes, she says. “So you can’t distinguish between police cars by their license plates?” That’s right, she says, and “that’s just one of the things about our police department that needs to change.”

Later, I will learn that there are only three states that don’t issue plate numbers to local police vehicles: Minnesota, Ohio, and New York. Over the next few days, I’ll ask various Minneapolis residents if they find it strange that the police cars don’t have unique plates. They’ll all look at me like I’m nuts. Then I’ll realize that although I lived in Minnesota for five years of my adult life, I never even noticed this fact, let alone identified it as a problem. I had to be standing at the site of the most famous police killing in our country’s history, next to a relative of the man who was murdered, before I noticed it.

In her book Lift Your Voice, Harrelson writes that even in Perry’s last moments, he saw the humanity of the officer whose knee was on his neck; that’s why Perry kept pleading with him. She tells me that there are body cam videos from the time just before the fatal nine minutes and 21 seconds. In one of them, Perry is handcuffed and pleading, “Why are you doing this to a man of God?” That’s important to her, that he identified himself as a man of God just before he died. He used to read his Bible every day, she tells me. Proverbs was his favorite book. His best friend now has his Bible and his shoes.

George Floyd is a symbol, an icon, a movement, a mirror that shows us our failures. His name represents all of the unnamed victims of police brutality. His story stands in for a larger story about the values this country is built on. But he was also a person—he was Perry. It’s Perry whose face was pressed into the pavement by a police officer’s knee while two others held him down. He was a gentle man who loved his family and lost his job because of COVID and made rap videos and took elderly relatives to church and struggled with drugs and read his Bible every day.

The memorial where I’m standing with Harrelson is just around the corner from the iconic George Floyd mural that was painted on the side of Cup Foods just after the murder, the one with the sunflower and the rays of light. That image appeared widely across the media (including on the July 1, 2020, cover of this magazine). In the mural, he looks angelic. That mural was the site of the original memorial, Harrelson tells me, and the flowers and candles and notes that people left extended all the way to the middle of the street. But the people who painted it didn’t actually know Perry, she says, and they didn’t get his face quite right. The mural was repainted after it was vandalized one night, and at the request of family and community members, Perry’s nose and lips were made less prominent, to make it look more like him.

On my last day in the square, I stop by the Pillsbury House, a community center that produces theater and community radio and runs a daycare and a bike repair shop, the latter staffed by returning citizens. I’m there to talk with Jeanelle Austin, a Fuller Seminary graduate who grew up in the neighborhood and moved back the week after Floyd’s death. She directs Rise and Remember, the nonprofit organization that takes care of the memorial site. She shows me the storage room where at any given time between 5,000 and 10,000 artifacts from the memorial site are being cleaned, preserved, categorized, logged, and stored. (Even more are stored off-site.) I ask her if artifacts is the right word. “They’re offerings,” she says. “They were brought to a sacred space and left there.”

We look at some foam board displays of offerings that have recently returned from a traveling exhibit. Austin tells me that the exhibits work best in places where people aren’t expecting them—a hospital, a library—because the element of surprise allows them to serve their purpose, which is protest. I spend some time looking at the foam boards. Many of the offerings are painted on cardboard or written on scraps of paper. “Rest in power, Mr. Floyd,” says one that’s brightly colored, with flowers surrounding an image of Perry’s face. The one below it is in a child’s handwriting: “#Black lives Matter, #BLM, Killer Cop’s I can’t Breath!!! BLM We need Justice!!!!!” Next to it, someone has written excerpts from Psalms 107 and 23 in Sharpie on a piece of a paper bag. One board has a strand of Mardi Gras beads with a sign that says, “All the way from Louisiana #We love you.” Another has a graduation cap.

“What I love about these pieces,” says Austin, “is that they tell us what people were expecting, what people were hoping, what people felt like they needed to say in a moment of urgency. That is what makes it so powerful: people didn’t get time to premeditate and ponder and perfect their message. It was just, what do I need to say right here, right now, before I go out and march?”

She explains the conservation process for offerings that have spent months outside, the way volunteers use Japanese paper and wheat starch paste to repair holes and tears. Sometimes people get emotional when working with the offerings. Austin encourages them to take a break, walk away, breathe, and not feel any urgency to return. Community-based conservation can be difficult, she says, because often individuals bring in their own stories of trauma. But, she adds, “we have been doing this work, remembering our stories collectively, for centuries. This is not new. It’s just a different approach to how stories are remembered and told.”

Driving home to Illinois, I think about the sacred space that’s been created at the corner of 38th and Chicago by neighbors, artists, activists, and visitors from around the world. I think about the layers of stories George Floyd Square tells and the way those stories are inscribed in the land and in the people’s hearts. I worry that I might not notice the sacred spaces in my own city: places of need and lament and celebration and communal protest, places where the operating principle is “people over property,” places where neighbors come together and take care of each other. “What is most sacred is usually right in front of us,” writes Steven Charleston in Spirit Wheel:

Right where we live.

The holy is in the everyday, the common, the simple.

It is hidden in places that have become so routine for us

That we hardly notice them anymore.

Back at the square, I asked Harrelson what she thought Perry would say if he could see the movement for justice that has formed there. “He was always saying, ‘ride on,’” she replied. “I think that comes from growing up in poverty. Even as a kid, when we had no running water and he had to use an outhouse, he took it all in stride.” She paused and chuckled. If Perry could see us now, she said, he’d probably tell us, “Ride on, ride on.”

Read an interview with George Floyd Square protest leader Marcia Howard.