This is my broken body

When illness took over my life, I developed a new understanding of the Eucharist.

In the decade that I taught classes on worship, I probably said “the work of the people” a gazillion times. Each and every time I believed that I knew what it meant. “Liturgy is the work of the people,” I said. “It’s what we do when we are gathered together as the body.” My students nodded in assent, audibly clicking away on their laptops, taking notes. As practitioners of worship we gloried in the gathered body. We explored the body as image, metaphor, symbol; as story and scaffolding; as liturgy and Eucharist and people; as salvation and strength.

In hindsight, however, I regretfully realize that I should have put it differently. I should always have talked about gathering together specifically as the broken body.

The story of Jesus begins with a baby born to a fragile family. It soon segues to the trauma of a broken body and the reality of unassuageable grief. Michelangelo’s Pietà comes to mind as an archetype of this grief: the body of a dead young man being given to his mother, who tenderly holds him, grieving. As the broken bodies pile up in Ukraine, the broken body at the center of Christianity’s story testifies to a shared, universal grief beating like a mother’s shattered heart at the center of the universe.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The theological traditions of the Eucharist have often obfuscated the archetypal story found at its center: grief and brokenness.

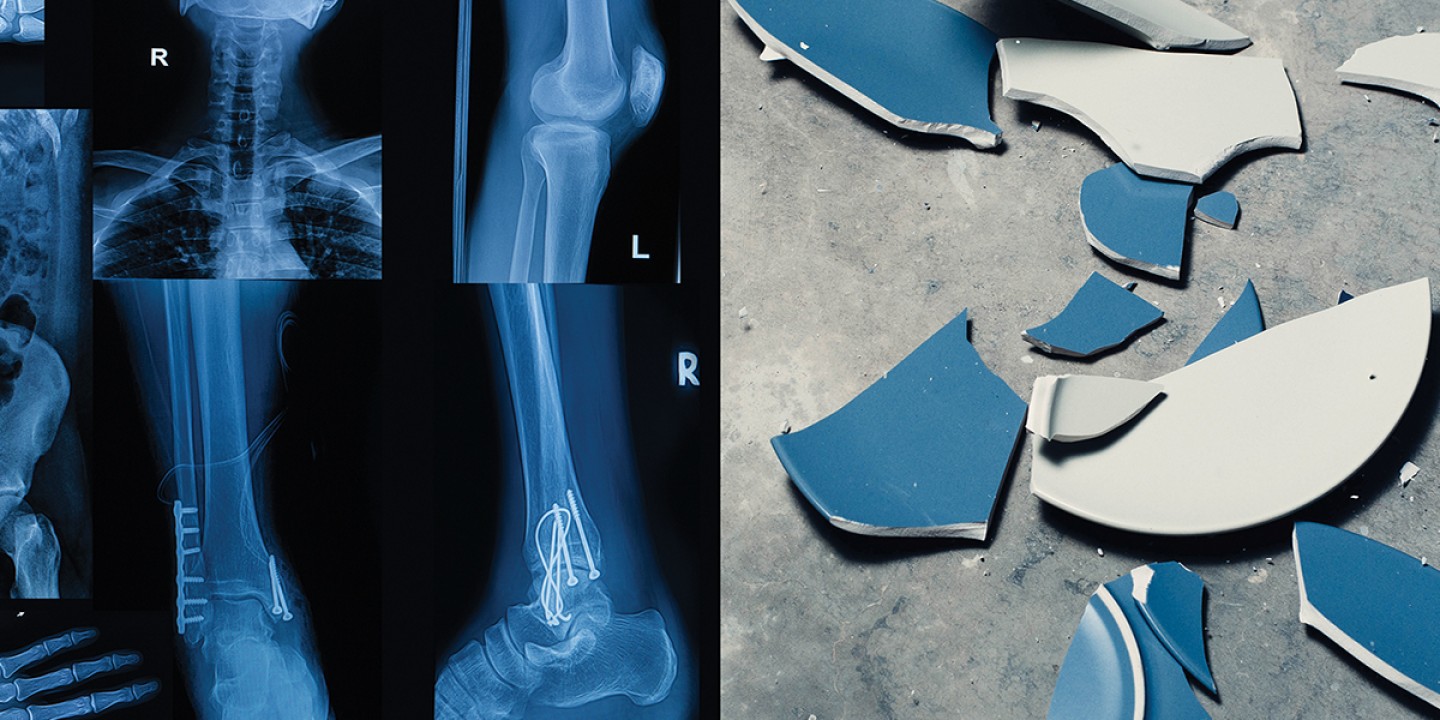

The broken body began to dawn for me one day at lunch with good friends. We were laughing and talking 90 miles an hour while devouring a gargantuan basket of chips and salsa. Without warning, my body began to short-circuit. First my vision began closing down; then my hearing started malfunctioning. Sweating and partially blind, I realized something was catastrophically wrong. I stood up to rush toward the bathroom so I could be ill in private, but as I took a first step I fell unconscious to the floor.

Mark—my pastor-colleague and best friend—rushed to me. He took my hand in his and said my name quietly, over and over like a responsive reading, while I lay unconscious. Mark’s wife, Leslie, called 911.

Splayed out on the restaurant floor waiting for God, I was surprised when the paramedics showed up. They shooed all the bystanders away from me, returning them to their lunches. One of them started an IV, another took my vitals, and a third played the role of St. Peter at the pearly gates, firing endless questions at me: “Name? Age? Birth date? Who’s the president? What month is this?”

But whatever had occurred in that moment I fell unconscious had short-circuited the link between my brain and the ability to speak. No matter how many times I was asked my name and age, I could not get my brain to provide the information nor coax my lips into speaking. Unable to open my eyes, I relaxed into the soft wads of semiconscious gauze that had been stuffed into the place where my brain had previously been.

At first I thought of this episode as a blip on the radar screen of my life—I thought that all would be well following a trip to the emergency room. I was supposed to give a keynote address the next evening at a conference at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, and it honestly never occurred to me that my body was flashing the check engine light and I needed to stop, wait, and reassess. Instead I kept my commitment to the Ghost Ranch conference and to a demanding schedule of travel and preaching and teaching over the next months.

But slowly I was forced to comprehend that on that day I fell unconscious, my body had stopped working as normal. “This is my body broken” became fact. Instead of flying off to speak at conferences, my destination became the Mayo Clinic. Illness took over my life.

I’d never been so grateful to be specifically Christian—with a Savior who specializes in broken bodies, massacred hopes, and disabled futures. Relegated from well-being and the places where I mattered, I turned toward brokenness and Jesus. Faces of the broken bodies I had ministered to in the decades of pastoral ministry began to surface. Even though I was solitary at home, I wasn’t alone.

I started watching the rituals of the Eucharist, the gathering of the broken body for worship, with new eyes. Having unwillingly become a member of Jesus’ “in crowd,” I parked myself in the back row at church—purposefully. It gave me a clear view of each row and its inhabitants as they made their way to the communion rail.

Very few of us walked without a limp. Edith with her Parkinson’s seemed to take the longest to get to and from the broken body, except for Liz, who’d had a stroke and made a turtle’s pace to Jesus. But then 91-year-old Marie brought Eucharist to a complete standstill as we admired her neon-yellow walker, adorned with tennis balls. Others of us limped with sore knees, creaking hips, broken hearts, and shattered hopes as we watched the healthy, sparkly ones (with toddlers or newly minted high school graduates or children with fragrant crayons in their hands) make their way forward. “The gathered, broken body,” I whispered, watching.

During much of the pandemic, I lived without the Eucharist—and I found it difficult to keep track of time. I began to realize that prior to COVID I measured each day in terms of its getting closer to (or farther from) my personal participation in that precious gathered, broken body in which my own body, sick and unable, is welcome and nourished and satisfied. Denied the broken body, I found myself craving Eucharist. My pastor brought communion to me, standing masked at my front door and handing it to me with a blessing. But without the gathered, broken body, it wasn’t Eucharist.

When we gather at the table of grief we are not alone. When Jesus says, “This is my body broken,” he normalizes not only my broken body but every other broken body across the eons and all the world’s surfaces. And when, at the foot of the cross, Mary’s grief compresses the very breath out of her body til she is bent over by it, every other person crushed by grief is also not alone. Whether broken in body or crushed by grief, we are never alone. We are the blessed and beloved broken body.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “This is my broken body.”