Discerning the body

Bodies get sick. What becomes of a church body when we enact unity at the table while ignoring our brokenness?

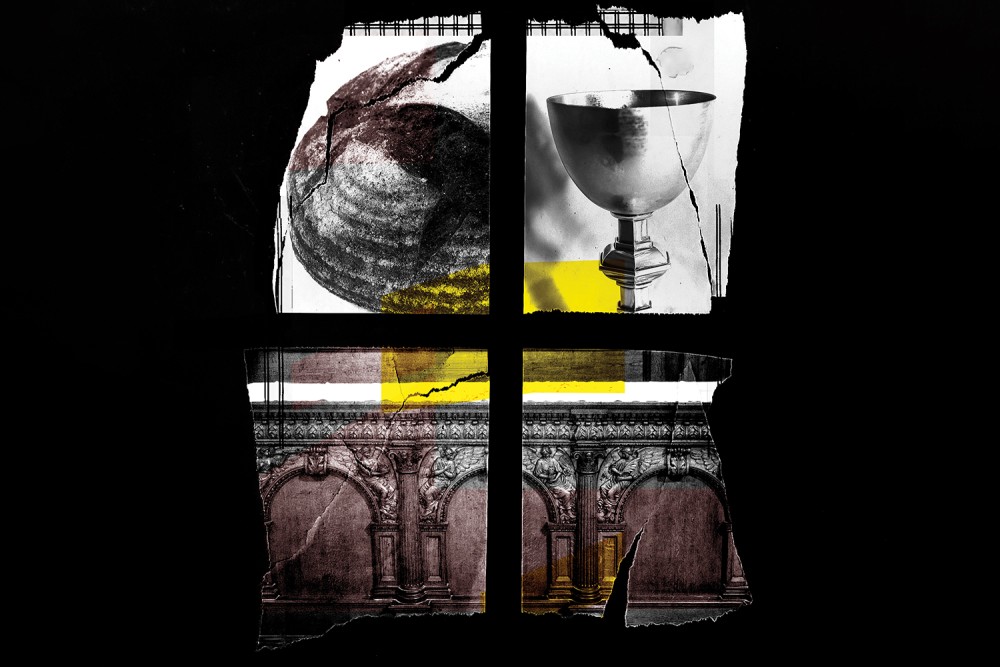

Century illustration by Daniel Richardson (Source images: Getty, James Coleman on Unsplash, Andreas F. Borchert / Wikimedia Commons)

On a frigid night in march, a woman wanders through a crowd with a loaf of bread. She pauses before each person and tears at the crust. “The body of Christ for you,” she hums before zigzagging back into the throng of bodies packed into the parking lot.

We have gathered to protest the incarceration of migrants housed in a concrete industrial park in an isolated New Jersey suburb. It is Maundy Thursday, and we are sharing Eucharist in this strange and desolate sanctuary outside a for-profit detention center. Many of the people out here are the family members of those who have been arrested for overstaying visas, for their illegality. They’ve come from low-paying jobs, pushing strollers and carrying infants, some still in the uniforms of house cleaners and fast-food workers.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The police have been dispatched, with their weapons and badges, to protect the detention center from our worship. I notice that a few of the people serving the bread have approached the police, holding out the rough edge of Jesus’ body. Each officer politely refuses, hands at their sides and on alert for disturbances in the crowd.

At that moment, I realize that the police can’t receive the bread of this community. To do so would interfere with their work. Our communion is a body—a body sheltering and comforting, angry and tired. Taking the bread and cup would confuse the status of these officers, disrupting their role in policing the bodies that make up this body.

Since then I’ve spent some time thinking about the officers’ refusal to receive. This hasn’t produced anxiety about the nature of a communion that could not embrace the armed guards around us. Instead, Eucharist at the detention center has offered some clarity about the possibilities and fractures of the body that celebrates the Lord’s death until he comes again. It has also illumined the possibilities for intervention when Eucharist is intertwined with terror.

Communion is a negotiation of borders and boundaries. Both porousness and rigidity are inherent in our reenactment of the supper Jesus offers his disciples. The disciples gather, displaced from families of origin, to take the meal Jesus says will make them one. Who is present and who is absent, we wonder? And what becomes of a body that tears itself apart in the eating?

These are questions that linger in Christian life, that tug at our practices. They are offered back to us in the testimonies of enslaved people who drank the blood of Jesus from the cups of their own slavers. In Slave Religion, Albert Raboteau recalls one such witness, William Humbert, a fugitive from enslavement in South Carolina. Humbert describes how enslaved people came from vast distances to gather for Sunday worship under the auspices of the White slaver church. There the sermon droned with the same moralism week after week: God demanded obedience to masters; thou shall not steal.

The White deacons distributed communion to those gathered. Then it was time for the long journey back to the scattered plantations. Humbert recalls how an hour after sharing Eucharist, the same White deacons met the enslaved workers on the roads. If they had not returned to the plantation within the time allotted by their passport, the White deacon slave patrols would “flog one of the brother members.” They did so “within two hours of his administering the sacrament to him.” Humbert offers his scathing judgment: “I thought that a man who would administer the sacrament to a brother church member and flog him before he got home, ought not to live.”

I keep this picture in mind, of deacons with the cup in one hand and a whip in the other, when I encounter these words of Paul: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be answerable for the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor. 11:27). It’s a shocking indictment. The church in Corinth is liable for the crucifixion of Jesus.

In a world increasingly polarized, as people recover from painful experiences of rejection and judgment in the church, I long for a meal without limits, where grace is abundant. But the testimony of William Humbert is also there, demanding my attention and my response. What does the Lord’s Supper, the meal that makes us one, become if we eat and drink factionalism?

This question drives Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. In 11:17–34, we learn that some people are coming early to the meal that is embedded in the liturgical celebration of communion. By the time everyone arrives, those early attendees have eaten all the food and some are drunk on the wine.

The early arrivers, the strong, are the leisure class who spend their days building their businesses and enjoying lectures and symposia. The strong are the educated and the wealthy of ancient Greece. The weak—enslaved people, day laborers, widows—arrive later. “One goes hungry and another becomes drunk,” Paul excoriates. The socioeconomically weak leave humiliated and hungry.

The strong have imported the social hierarchies of their dinner party economy into the Lord’s Supper. After laying out what he’s heard, Paul instructs the Corinthians: “Examine yourselves, and only then eat of the bread and drink of the cup.”

Paul’s words here are at the root of the “pledge of love,” a practice my church engages one week before we receive communion. In 1527, Balthasar Hubmaier offered a set of questions to the Christians who would later identify as Anabaptists: “Will you love God before all things?” asks the text in the Voices Together hymnal. “Will you love and serve our neighbors? Will you support and challenge one another, speak and hear the truth, cease what causes harm to our neighbors, and do good to our enemies?”

In unison we respond to these questions, “By the grace of God, I will.”

Mennonites take this pledge because in baptism we have freely and wittingly chosen to discern the body together. We submit to one another, to the difficult and dangerous work of sorting out the kind of life we will lead. The table is a re-membering, a meal that reunites the members of our baptized bodies. The table is Christ’s, and we are the body Jesus. We hold in reverence what has been entrusted to us: “Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (Matt. 18:18).

Our congregation receives communion in a variety of ways, but I am especially attentive when a group of people come forward and form a small circle beside the table. When I am the presider, I hand the bread to the first person, offering them a torn piece of the loaf with the words “the body of Christ, for you.” Around the circle, each person tears the bread, places it in the palm of their neighbor, and repeats the words. The cup is then passed around the unbroken circle as well.

I’ve noticed that at the end of this small-group ritual, people linger for a moment before taking their seats. They often embrace. Communion is a corporate grace. It requires other people. To receive the bread is also to pass it on. To take the cup is to pour it out for another. “You are what you eat,” my congregation has heard me say over and over. You become the body of Christ in the eating of the bread, become the actual, living person of Jesus when you take the cup.

I also know that bodies break and bodies get sick. Bodies harm and destroy themselves. What becomes of us when we embody unity while ignoring the fact that we have come apart?

For centuries, Paul’s words about eating and drinking “in an unworthy manner” struck fear into pious hearts. Among Mennonites, these words were interpreted with a wide berth to condemn “worldliness” like playing a piano or reading mystery novels. Mennonite bishops appeared at doorsteps to issue bans from communion on families who were caught at a movie theater.

In the Catholic Church, bishops are in the habit of banning from Eucharist elected officials whose stance on abortion differs from that of the magisterium. Each election season newspapers report on the latest political candidates barred by conservative bishops from receiving communion in their dioceses.

Withholding communion as a form of punishment and control is well established in church history. In another account in Raboteau’s book, a formerly enslaved worker named James Sumler notes the irony of White slavers who chastised their enslaved workers for taking communion in a “disorderly manner.” “I thought he was disorderly himself, for he kept slaves,” Sumler concludes.

For those who require moral and ethical purity before receiving the elements, communion will lose its powers if infected by human sin. But discovering illicit rock albums and controlling the church’s national politics are shoddy simulacra of the admonishment to discern the body. Instead, to understand what Paul means, I turn to ministers like Jonathan Lankford.

Lankford was the White lay minister of the Baptist church in Black Creek, Virginia, a congregation that included enslaved people, White slavers, and White people who were not slavers. Historian Randolph Scully writes that in December 1825 Lankford made an announcement to his stunned congregation. “In Justice to his conscience” he could no longer offer the ordinances of baptism and communion “owing to his oppesition [sic] on the subject of Negro Slavery, a part of the church being Slave holders.”

White members of the church were outraged at the announcement. For seven years Lankford had offered ordinances to all members of the church. What had changed? Slavery was a matter of individual conscience. Were not all welcome at the table, both slave and free? Throughout their report condemning Lankford, White church leaders protested that the call to unity demanded by the gospel outweighed the conscience of their minister. Whatever happened in the cotton fields and plantation houses had nothing to do with the body and blood of Jesus shared in the plate and chalice of the church.

Eventually Lankford was excommunicated for his attempt to “split the Church asunder.” He continued to farm nearby, a local exile.

I wonder what led him to discern the body. At some point, he came to believe the brokenness in a church of slave and free was total. To enact a ritual that made concrete their unity while the body cleaved apart was to negate the act itself. The sacrament had failed not because of any inherent flaw but because people hid their sin behind the veneer of unity.

I am on the lookout for practices that invite both accountability for harm and restoration without appealing to police and prisons. From time to time I get a glimpse of this possibility in church: of the ways a faith community, outside the state apparatus of surveillance and punishment, can attend to brokenness and to those who cause harm. We are built for this. The church is a place where no one is expendable and where harm requires repentance and repair.

When our community is in agony from church members hurting one another—when a woman in the church suffers abuse at the hands of her partner, when someone is harmed by a fellow church member’s racism or homophobia—we are called to pause, examine, and offer creative and life-giving pathways for repair. When that harm is grievous, when there is danger that the offender will not acknowledge their harm, we let the offender go the way they have chosen. We are ceaseless in our hopes for their return.

For Paul and the early Christians, the nitty-gritty of common life was inseparable from consuming the Lord’s Supper. Our bodies are caught up in the body of Jesus, and that body eats and drinks a common meal. I think of this when, in my church, the Holy Spirit falls not only on the elements but upon us, the body that receives them. “Send your Spirit upon us,” I pronounce, my hands lifted above the heads of the people of my church, “so that the bread we break and the cup we share may be the communion of the body of Christ.” I look at the faces before me, trusting this work. “Send your Spirit upon us so that we can live, conformed to Christ.”

Unlike my forebear Mennonite bishops, I don’t spy for personal infractions to test the Spirit’s work in the sacrament. Instead, I am watchful for the care of this body. Do we have enough to eat? Are there some of us buried in debt and troubled by the future? Have we ensured that those without access to mental health resources are receiving the care they need? Are we encouraging those in our church who are in recovery? By grace and through the power of the Holy Spirit, somehow we find our way to these questions. We repent of our failure. We grow in love.

On March 20, 1977, Archbishop Óscar Romero suspended all masses throughout his archdiocese in El Salvador except for one: a single mass to be held at the cathedral in San Salvador. A week prior, Romero had buried his fellow priest and beloved friend Rutilio Grande. Grande was assassinated by Salvadoran security forces for his work organizing rural farmers and his outspoken criticism of the government. The mass at the cathedral would proclaim the unity of the church while protesting the murder of Grande.

La misa unica was a politically charged decision denounced by the Catholic oligarchs. Wealthy landowners reacted with horror. They would be forced to stand for three hours in the grime and heat of the city among the Salvadoran poor.

Theologian Jon Sobrino described Grande’s death and the “one mass” as the conversion point in Romero’s life. At his election, Romero was assumed to be a safe and banal choice for archbishop during a time of mounting political instability. But something shifted. “Never again would he be capable of separating God from the poor,” writes Sobrino.

Tens of thousands of people appeared at the cathedral for mass. One hundred and fifty priests concelebrated alongside the archbishop. Over the next three years, many of those priests would die at the hands of the Salvadoran death squads and security forces trained at the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia (now Fort Moore). Romero, too, would become a martyr for his love of God and the poor, assassinated with a single shot as he held the host above his head.

But before all of that, at la misa unica, Romero looked out on what he called in his homily “the pilgrim church.” “The mass is Christ,” he told the worshipers who gathered outside the cathedral—the rich and the poor, the landowners and the campesinos. To participate would require the wealthy landowners, the death squads, the soldiers, and the cardinals to move their bodies and their lives into the crowds of the poor, where the mass would denounce the satanic power of Grande’s killers. They would bend their knee before the God who owned their sole allegiance.

It is a stark and haunting image, one that draws me back to 1 Corinthians and the words of institution I say before my own congregation. “Whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup,” writes Paul, “you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.” We are proclaiming Jesus’ death, the death of God who joins God’s self to creature life and becomes creature food.

My attentiveness to the health of my congregation, to the bodies that re-member before the table, is borne of awe. The wholeness of our sacramental life is not guaranteed by the gift of our practice. Sacraments go wrong because they exist within communities of people, and people are flawed and broken. We break things. Sometimes we break one another. We are no different than the people of Corinth, no different than the church of Black Creek, no different than the masses who gathered at the San Salvador cathedral. If we proclaim the Lord’s death in our common meal, we will find a people who are undoing the structures of economic violence that choke life from the world. If not, we will find only a sick body on its way to death.