Letting go of the plan and embracing the dream

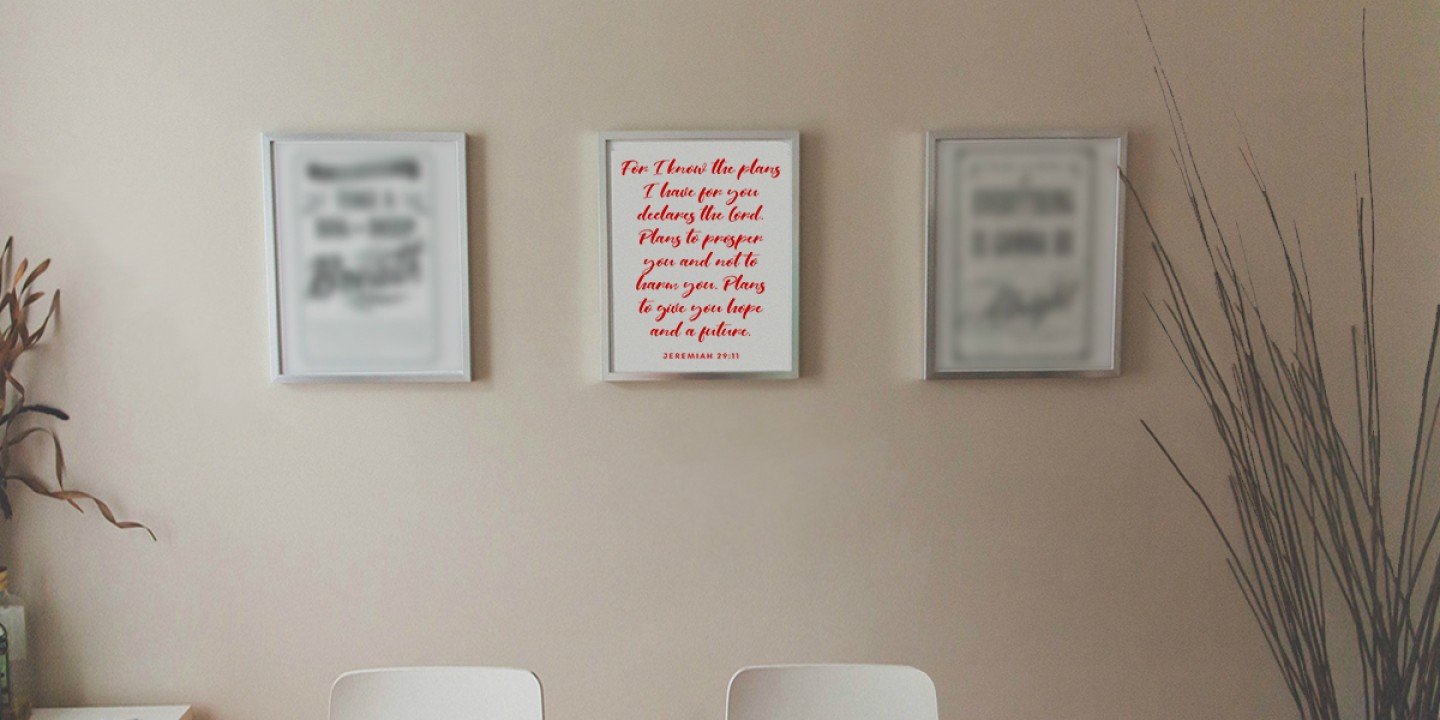

I used to have Jeremiah 29:11 in a frame on my wall. I don’t anymore.

I was 17 years old when someone first gave me Jeremiah 29:11 as a gift: “‘For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord, ‘plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.’” The verse was given to me in a greeting card when I finished high school. Four years later, I received it again as a college graduation present, this time in block letters on the cover of a prayer book. A year after that, my husband and I found the verse among our wedding gifts, penned in calligraphy and set in an elegant silver frame. For years, the frame hung on our living room wall.

“For I know the plans I have for you.” Or, to put it in language common to American evangelicalism, “God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.” In the circles I grew up in, this “wonderful plan” was a core belief. As a Christian, I wasn’t simply saved, forgiven, and loved; I was held in the sovereign will of a God who ordained my comings and goings, my nights and my days. This meant nothing would happen to me—nothing could happen to me—outside God’s plan.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I don’t remember when I took the silver frame down. But at some point, I decided that believing in Jeremiah 29:11 as a promise to me required more than blind faith and a muted intellect; it required a suspension of my moral judgment. I could not perform the mental and spiritual gymnastics The Plan requires without twisting God into someone coldhearted and ugly.

If God had a plan, then at every possible fork in the road God was making intentional choices to act or not to act, and those choices were pre-scripted. (Mack truck about to hit toddler—divert or not? Cancer about to kill young woman—heal or not? Mass shooter about to enter elementary school—intervene or not?) If God had a plan, then the divine capacity for empathy—for genuine surprise, true horror, unyielding sorrow—couldn’t help but be blunted. Why would anyone grieve their own perfect plan?

Though the process of letting go was very hard, I no longer cling to the plan. I believe in something more tender, riskier, more fragile. I believe that human freedom isn’t an illusion; it’s the real deal. God works with the free choices we make in the free universe we live in. God dreams for us, hopes with us, and grieves with us in real time. God works in subtle, mysterious ways, always and everywhere, to redeem us without violating our freedom.

I don’t know what the best metaphor or analogy is for this “plan-less” God. Perhaps God is like a novelist, at once writing a story and allowing his characters free reign on the page to “write themselves.” Perhaps God is like a conductor, calling forth a piece of music with the skilled movements of her hands, while also requiring the artistry of each violinist, cellist, flutist, and clarinetist in her orchestra to make a symphony come alive. Perhaps God is like a human parent, wanting so much to ease the way for his child, while also knowing that the child must learn to stand, walk, run, tumble, fall, fail, and recover without oppressive interference.

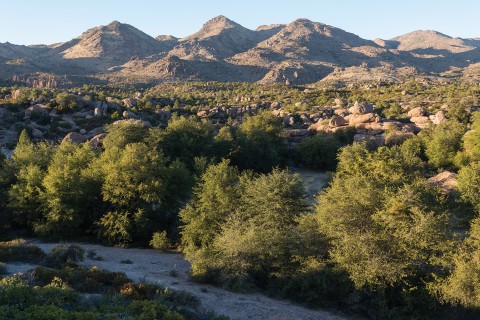

A plan-less God doesn’t predetermine our days and nights. God walks into them with us, hoping, dreaming, and engaging with us in all the messy, complicated situations we face as vulnerable human beings. God doesn’t hover over creation with a giant planner, ticking off events as they occur; God experiences reality on the ground, just as we do. Determined to accompany us, God rounds every bend in the road, gasping at each glorious landscape, celebrating every mile we conquer, mourning the weary aches and broken ankles we suffer along the way, and working at every instant to birth fresh possibility and goodness into the lives we shape.

If I sound like I’ve arrived, I haven’t. If I sound like Jeremiah 29:11 no longer attracts me, it does. There are days—many days—when I ache for the certainty of a perfect plan. I crave order. I run back to my old version of God again and again because I fear my own freedom, and I fear the chaotic freedom of the universe.

But then I come back to this: if I can let go of the plan, I won’t have to strain and struggle to explain bad things away. I’ll never have to make God ugly in order to make God good. I’ll have one more reason to stand in awe of who God really is: a humble servant king, willing to relinquish ultimate power and control for the sake of love.

Moreover, if I’m willing to surrender the plan, I can learn to pray in ways that are not superstitious and frenzied. Prayer can cease to function as a talisman, warding off misfortune and punishment, and become instead an intimate conversation between lover and beloved. If I’m willing to walk in uncertainty, God might show me how redemption is enacted in real time—not through coercion, firing off executive orders and pre-scripted memos, but through improvisation, transposing keys and sounding new notes of hope for an evolving world. God as jazz musician, not CEO.

What would it be like to embrace such a God? What would it be like to rewrite the promise? “For I know the dreams I have for you,” whispers the Lord, “dreams to bless and not to blunt you, dreams to kindle your courage in a future grounded in my love.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The plan and the dream.”