The plain, difficult sense of scripture

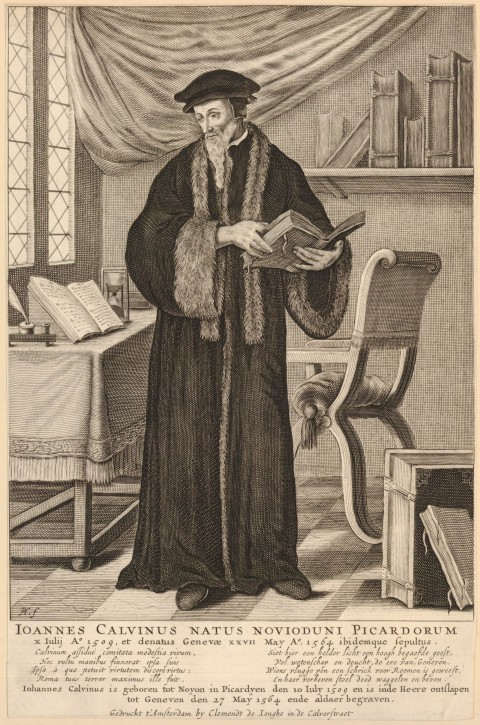

Calvin argued for the self-evident clarity of the Bible—the same Bible he wrote thousands of pages about.

In his preface to the Geneva French Bible, John Calvin exhorts: “You who call yourselves bishops and pastors of the poor people, see to it that the sheep of Jesus Christ are not deprived of their proper pasture; and that it is not prohibited and forbidden to any Christian freely and in his own language to read, handle, and hear this holy gospel.”

This statement is about the church and its book, a community made by and for knowing God’s purposes and thereby reflecting God’s glory by reading, handling, and hearing this good news. For Calvin, the life, identity, and well-being of the church can only be sustained and enacted by the Word of God that constitutes, redeems, and re-creates our life. By this pasture alone does knowledge of God come uniquely and specially to God’s people. What the church is hungering for, what alone can nourish and sustain us in our life of faith, comes from our having direct and unmediated access to the Word written.

Calvin, like many of the Reformers, spoke confidently about “the perspicuity of Scripture.” He was convinced that just as the gospel of Jesus Christ is available for every kind of person, so the Bible, which proclaims this good news, must be as well. This double conviction is evident from his very first Reformed writing, the preface to Olivétan’s New Testament. He explains that the fulfillment of the Old Testament law and the reconciliation of God in Christ “is what is stated plainly in the [New Testament] and set forth there openly.” The purpose of the translation is “to enable all Christians, men and women, who know the French language, to understand and acknowledge the law they ought to obey and the faith they ought to follow.” Scripture makes plain both our human need and God’s way for salvation; this is the core of the claim of perspicuity.