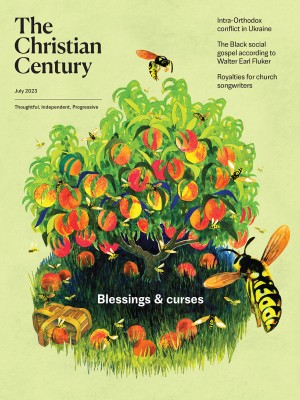

(Illustration by Daria Kirpach)

Our house came with a chicken coop, complete with a fenced-in chicken run. We were used to cats: after the one we had for 16 years died, we loaded up with four more. Four cats is a lot, but that didn’t prepare us for chickens.

Our roofer, an animal lover himself, gifted us with six chickens: two Ameraucanas, two Plymouth Rocks, and two Rhode Island Reds. My wife, wanting them to be tough, named them after her favorite Game of Thrones characters, all women not to be trifled with: Cersei, Catelyn, Arya, Daenerys, Sansa, and Brienne.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I decked out their chicken coop to the hilt. Beyond the standard feeders and waterers, we installed an automatic door that let them out first thing in the morning and closed after they settled in for the night. We set up cameras inside and outside the coop. I put in a sprinkler system to cool them in the heat and a heater to warm them in the cold and, in an attempt to weatherproof them against Texas’s brutally hot summers, even rigged an air-conditioning system using frozen water jugs and a fan. I was determined to turn them into tech natives, outfitted with the latest (chicken) gadgets.

We soon learned that everything in the neighborhood wants to eat chickens. Dogs, possums, vultures, hawks, eagles, coyotes, raccoons, snakes, fleas, ticks, and sometimes other chickens. We’d occasionally catch our cats eyeing them from the window. Perhaps they wanted to make friends; perhaps they wanted to make nuggets—we couldn’t tell. “Tastes like chicken” probably applies across the animal kingdom. We spent what many would consider an inordinate amount of time worrying about our hens. Unlike cats, chickens seem so different that it’s hard to know how to take care of them. We loved them but generally had no idea what to do with them.

Chickens are smart, curious animals that love to range free. In many places, chickens roam wherever they want, freely following their chicken instincts, pecking about, searching for tasty treats, scratching around in their wide-open chicken worlds. Keeping them cooped up bores them and tends to breed bad behavior. We discovered that pecking order is a real thing: chickens staunchly and often cruelly maintain social hierarchies. We found that the more cooped up we kept them, the more they bothered and bullied one another. When free-ranging, however, they worked as a team to explore a world they found endlessly alive with possibility.

We tried to let them out at least once a day, when they would quickly begin making the rounds at their favorite foraging spots or shaded areas. We loved it when they found some cool patch of earth and laid down as a group, usually on their sides. They seemed to rest easier knowing we were around to protect them. In those quiet moments, we felt like we had led them to green pastures, beside still waters. The earth felt at peace, our souls with them restored.

Backyard chickens usually live three to eight years—a lot less than indoor cats. We started with six birds. Four years later, only two remain, Sansa the Red and Arya the Plymouth.

I had to put Cersei down after a stray dog attacked her. I had never put down a chicken or really any animal. I found YouTube videos that made it look easy. It wasn’t. I made a mess of it, and she suffered as a result. Catelyn was killed by the others. We found her battered body in the coop and assumed she had been bullied to death. Dany got sick and died after barely moving for days, just sitting there like something awful was happening. The Texas heat killed Brienne, along with tens of thousands of farm animals that long terrible summer. I tweeted about it, and someone honored her passing with a beautiful quilt that now hangs above our fireplace.

Arya almost died when a small dog with a Napoleon complex bit her, taking two overcompensating bites out of her backside. My teenage daughter and I spent two weeks nursing her, isolating her in the house and carefully tending her wounds. Fighting off infection required that we clean her injuries twice a day, which obviously pained her. Over time, she learned to trust us and would wait patiently as we treated her in our clumsy, amateur ways. Her tail feathers, one of the most physically striking things about chickens, never grew back, but she pulled through. When Sansa started sitting around one day, we feared that whatever got Dany was killing her too. She stayed indoors with us for a week, and like Arya, she learned to accept us handling her until she got better.

Scripture has a few things to say about chickens. Psalm 91 and Luke 13 portray God caring for Israel like “a hen gathering her brood under her wings.” My favorite novel, Walter Wangerin’s The Book of the Dun Cow, tells the story of a hen and a rooster tasked with shepherding creation against a menacing evil, kept at bay only so long as God’s creatures love one another.

For me, the wonder of chickens is the chickens themselves—and how life with them comes with, to quote philosopher Cora Diamond, “a sense of astonishment and incomprehension that there should be beings so like us, so unlike us, so astonishingly capable of being companions of ours and so unfathomably distant.” Whatever similarities chickens bear to humans—enough to allegorize pecking orders—and regardless of the human names we give them or the human stories we tell about them, despite the technology we deploy to take care of them, and no matter how far our worries go empathizing with them, nothing quite captures their utter uniqueness and the sense that God created them simply for them.