Lessons from downsizing my office

As I worked my way through old files and photos, I met with three kinds of sadness.

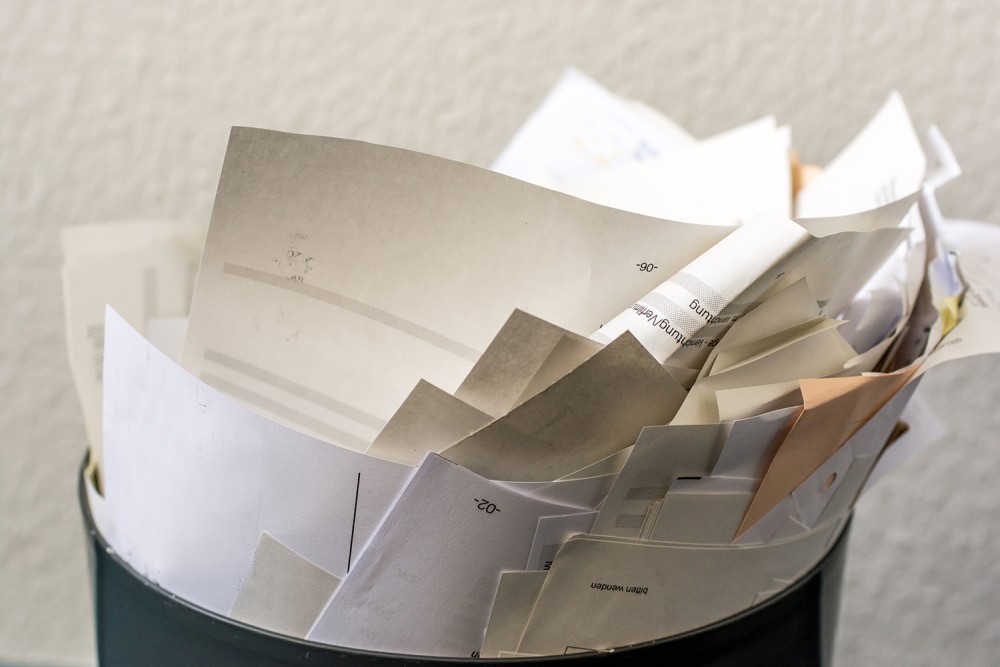

(Photo by Ralf Geithe / iStock / Getty)

I think of myself as a snail and not a squirrel: I don’t accumulate things, dwell on photos or messages or memories from the past, or linger over decisions made or mistakes that can’t be reversed. Still, recently I decided it was time to downsize: too many books, too many paper files, too much of the past to see the present or perceive the future.

Turns out if you’re going to be an accredited snail, you don’t simply need not to hoard—you must actively jettison. Discarding is a daily discipline of parting with things you might just possibly one day miss. I spent a couple of days with a paper shredder, going through old personnel files, correspondence, minutes of meetings, that helpful photocopy on group dynamics I meant to read, photographs, and useful trinkets that ten years on have yet to come into their own. It brought upon me three kinds of sadness.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Sadness one was the books and pleadings people have sent me in hope that I might help them publicize their work. To throw such a letter away feels like a withholding of blessing. But what has become of this correspondent now, and how many such parcels to strangers have they since sent?

Sadness two was the files that contained painful memories: staff under disciplinary procedures after numerous documented attempts to resolve unhappiness in a less adversarial way; records of grief, suboptimal behavior, and senior figures trying to be fair to fragile human beings while protecting and upholding those on the receiving end of wayward conduct or poor performance. Where are these people now, and do they look back on these disputes with sorrow, bitterness, or paradoxical gratitude?

But sadness three was the most surprising: write-ups of senior staff and trustee blue-sky sessions—dreams of a stirring future, confidence that obstacles will quickly be overcome, fervid flip chart slogans proclaiming unity and energy and strength. How many times have I sat in a room where colleagues have taken time out of their schedule to hope, plan, prepare, envisage—and come away seeing the good, building on assets, genuinely connecting with the neighbor that most of the time they can’t abide? How many of those projects have come to fruition?

There are plenty of guides and studies and courses on how to be a leader. Some claim to be biblically grounded, although I’m not sure I really aspire to be a leader like David or Solomon or even Peter or Paul. But these two days, put aside purgatorially to shred those things that are no longer needful unto salvation, have maybe taught me more than I can learn from a pep talk by a business school guru or retired NCAA coach.

Sadness one, the unsolicited letters to which I seek to respond politely but which eventually I discard, tells me about my latent messiah complex. I really would like my sermons, publications, and broadcasts to move, transform, and heal millions. But the truth is I have little or no control over how my words and gestures are heard or understood, and I’m subject to projections from diverse listeners and readers who are on their own journeys and whose genuine connection with my identity or message may be only tangential. I can’t solve other people’s problems. I can, however, modestly try to bless them in a way that points to Christ and not to me.

Sadness two, the painful records of relationships gone wrong, teach me to be humble in my expectations of community—congregation, organization, institution—and of my ability to influence it for good. It’s facile to throw my arms in the air and ask why can’t everyone just get along; it’s up to me to set a culture where people aspire to be good colleagues and bring out the best in one another, where everyone knows that disrespecting or undermining others will be addressed rather than condoned. Meanwhile, keeping careful records of conversations had, reports made, warnings communicated, and commitments undertaken isn’t technocracy; it’s the faithfulness of the tiny particulars rather than of the grand gestures or fine words.

Sadness three, the faded dreams and thwarted visions, remind me that my life will end in failure. I’ve been blessed to lead two visible and celebrated institutions, Duke University Chapel and St. Martin-in-the-Fields, but Jesus warned us that from the one to whom much has been given, much is expected—and these are places where keeping things steady isn’t what the kingdom requires. What he could also have said is that there are two kinds of failure: failing to reach stellar aspirations, and failure to maintain such achievements as you’ve attained. Those lauded for their success simply experience the second kind rather than the first.

But all that sadness yields ultimate gratitude. So much good work, so many conscientious colleagues, so many good intentions. As I looked at 20 trash bags of discarded materials (all recycled, don’t worry), I recalled the 12 baskets left over after the feeding of the 5,000. My sadness is my failure to find a purpose for, redeem, or realize every gesture, incident, and detail in the inbox of ministry. My joy is that the Holy Spirit has no such problem. What is done for love, says Thomas à Kempis, becomes wholly fruitful. Not by itself, but by the Spirit through whom nothing created is ultimately wasted.

In the end I’m not sorry about my limitations; I’m instead glad that the eschatological fulfillment doesn’t depend on my capacity. And I’m joyful to be invited to be part of a community called to anticipate it imaginatively and faithfully.