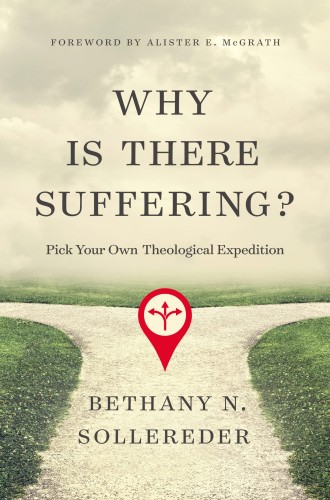

A theological exploration in the style of a Choose Your Own Adventure book

Bethany Sollereder explores different approaches to understanding suffering—and enacts one.

In his book Transdisciplinary Systems Engineering, Azad M. Madni defines elegant design as that which “focuses on the total [user] experience and exploits systems thinking, probing and questioning.” Elegant design “encourages exploration” while using “appropriate analogies and metaphors to simplify system architecture.” Madni could just as well have been describing the ingenious architecture of this book by Bethany Sollereder, a theological exploration that follows the structure of a Choose Your Own Adventure book.

Why Is There Suffering? is less a theological discourse than a thought exercise in which the reader is the object of their own experiment. Using the format of the famous 1980s children’s books (and more recent Netflix shows), Sollereder guides the reader in traveling down various theological pathways that explore theodicy, the question of why suffering and evil exist. Different paths lead to different conclusions: God cocreates the world with us (chapters 9, 11, 17, 23, 26, 28), there is no God and/or God is impersonal (chapters 13–22), there is an afterlife (chapters 30, 34, 40, 41), and so on. Sollereder intends the book to be a “lighthearted adventure” through a “heavy topic,” one in which the reader has an opportunity to resonate with different views in unexpected ways.

At first blush, this book might make excellent reading for an adolescent whose emerging free will urges them to have some choices over their own learning. Sollereder never portrays suffering or evil in specific ways: there are no graphic illustrations of violence or references to real-life tragedies like school shootings or natural disasters. The paths exploring animal salvation might even have been written with younger audiences in mind.