A robot learns to be a child

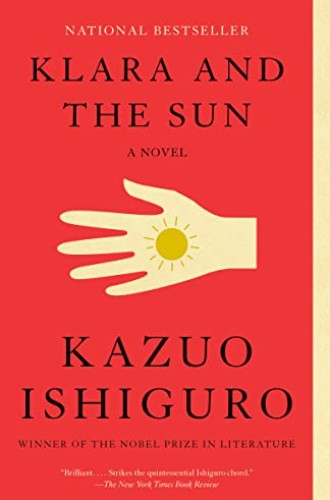

The central character of Kazuo Ishiguro’s virtuosic 2021 novel is an “Artificial Friend” with a young girl’s body.

Walking across a university campus recently, I noticed several small white plastic boxes on wheels. They scurried along sidewalks, crossing streets when traffic cleared, obviously headed somewhere. They were take-out robots, summoned by students on their smartphones to bring tacos or pizza or tandoori chicken to the residence halls. One of them approached me, blinked its lights, and waited for me to pass by. It declined to tell me where it was going.

The central character of Kazuo Ishiguro’s virtuosic 2021 novel is a robot of quite another sort. (Think of this year’s smartphone compared to a 1970s mobile phone with its bulky battery pack.) Klara is an “Artificial Friend” with a young girl’s body, able to act and speak and think for herself. As the novel opens, she is waiting hopefully for someone to choose her from the showroom where she and her AF friends are on display, though she knows she is a generation behind the newest models nearby.

Philosophers and poets have long puzzled over what it is like to experience the world as a dog or a bat or a beetle, but Ishiguro attempts something even riskier and more ambitious. The story that unfolds in Klara and the Sun is told from beginning to end from inside the mind of a—what shall we say? Robot? Automaton? Artificial person? Animatronic doll? Each is true in a sense, but none does justice to the richness and complexity of Klara’s life.