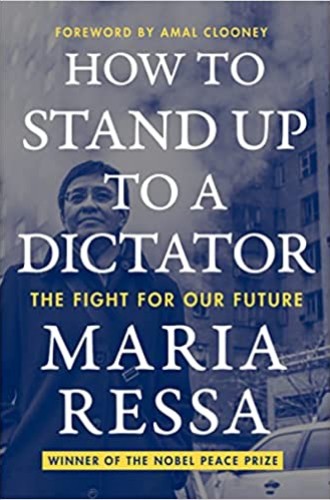

Maria Ressa’s fight for democracy in the Philippines

The renowned journalist explores how the authoritarianism and corruption she has been fighting for 35 years are now aided and abetted by the internet.

In the early ’90s, my wife and I taught at a small college in the Ilocos Region of the Philippines. Telecommunication was rare, difficult, and, by today’s standards, glacially slow. We didn’t have a telephone, nor did anyone else we knew. You could not reach thousands of viewers, followers, or friends with the click of a button or by asking Alexa to do it. The words smart and phone had nothing to do with each other.

I thought often of that era while reading renowned Filipina journalist Maria Ressa’s memoir. Although the how of the fight she alludes to in the subtitle has changed—it has become a high-tech digital battle—the goal has not: democracy, equal opportunity, and socioeconomic justice for all Filipinos.

Ressa explores how the authoritarianism and state corruption she has been fighting for 35 years are now aided and abetted by the internet and social media. Whether it be covert online electioneering, reinventing history, or marketing disinformation as fact, the greatest challenges Ressa faces are online. “This book,” she writes, “is my attempt to show you that the absence of law in the virtual world is devastating.”

After outlining her childhood and college years, Ressa reviews the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship (1965–1986), the People Power movement and Corazon Aquino’s presidency (1986–1992), and the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte (2016–2022), who returned to the devastating economic corruption and state-sponsored violence so prevalent during the Marcos years. Finally, she turns to Marcos’s son, Ferdinand Jr. (known as Bongbong), who was elected president last summer.

In 2012, after leaving jobs at CNN and ABS-CBN (the Filipino national news network), Ressa formed her own national news network, Rappler. She imagined it as a Venn diagram with three interlocking circles: investigative journalism, technology, and community. “Rappler builds communities of action, and the food we feed them is journalism,” she writes.

Since the Philippines was then leading the world in social media use—she writes that as of 2011, 94 percent of Filipinos had mobile phone access—Ressa sought to use the internet as a force for democracy. With Egypt and the Arab Spring as models, she observed how the internet, and particularly social media, was “breaking down people’s fears, enhancing their courage, and fast-tracking protests that otherwise might have taken years to organize.” The authoritarian governments could not restrain the protest movements because they were “modeled on the networks of the web: loose, nonhierarchical, leaderless. Dictators didn’t know who to arrest.”

Rappler took off and was extremely successful because it “fused online journalism with social network theory.” A big part of the network’s success was due to its use of Facebook, which at the time was surging in popularity. In 2016, on the verge of the presidential election, the average Filipino had 60 percent more Facebook friends and sent 30 percent more Facebook messages than the global average.

By this time, however, the role of social media was starting to cut both ways. The political right had started using bots and fake accounts to promote conspiracy theories, fake news, and outright lies, all to whip up fear and anger, polarize the electorate, and create division. The followers and campaign operatives of both Duterte and Donald Trump used these strategies, and the resulting propaganda networks were extremely successful.

Ressa believes that Facebook played a significant role in both men’s elections as presidents in 2016, and she spends significant time critiquing the company. She writes:

There are three assumptions implicit in everything Facebook says and does: first, that more information is better; second, that faster information is better; third, that the bad—lies, hate speech, conspiracy theories, disinformation, targeted attacks—should be tolerated in service of Facebook’s larger goals.

She blames much of this on Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, whom she knows personally. She asserts that Zuckerberg has chosen company over country and allows lies to be prioritized over facts, which has led to the destruction of “the information and trust ecosystem which gave birth to Facebook.”

It was within this perilous media climate that President Duterte recognized the threat that Ressa and Rappler represented to the culture of disinformation that he directed, and thus to his leadership. She was attacked by his followers in the right-wing media and then by the Filipino legal system. Ten warrants were issued for her arrest. The government brought eight charges against her and Rappler, including cyber libel, tax evasion, and securities fraud. These charges carry a cumulative prison sentence of more than 100 years, and while some have been dismissed, she is still fighting others in the courts. The new president, Bongbong Marcos, who relied on his own media propaganda machine to get elected (and to reinvent his father), has continued Duterte’s volatile media strategies and legal attacks against her.

Ressa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021, along with Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov. This has helped magnify her voice as well as the voices of other journalists who risk their lives to do their job—simply to report the news. She continues her work at Rappler in the hope that others will replicate it. This commitment was evident in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech:

Our greatest need today is to transform the hate and violence, the toxic sludge that’s coursing through our information ecosystem, prioritized by American internet companies that make more money by spreading that hate and triggering the worst in us. Well, that just means we have to work harder. In order to be the good, we have to believe there is good in the world.