From inertia to (small) action

Mai-Anh Le Tran bravely jumps into the space where theory meets practice.

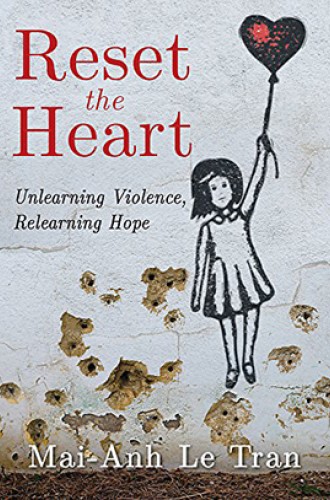

So are you going to do something?” a colleague asked Mai-Anh Le Tran. Tran, who taught Christian education at Eden Theological Seminary in St. Louis, had just returned home after being away the weekend of Michael Brown’s murder. Tran answered by writing this book, which asks readers this same question.

Doing something is important to Tran. Her cardinal sin is non-action, which leads to a “distortion of the sacred vitality and intimacies of bodies,” made worse by our rationalization of it. The sin is particularly egregious because violence, whether active or inactive, stunts human ability to imagine a future of hope, which means that it prevents our ability to do theology and live bravely into a future we have not seen. Tran finds this violence of inaction especially present in white Protestant churches that have met calamity with “indifference, paralysis, apathy, exasperation, and even downright resistance.”

I had little choice but to engage actively in Reset the Heart to keep up with the turns in framework and vocabulary, and it was fun to do so. I felt like a new student speed-walking to keep up with a cooler, smarter, much faster upperclassman in her turns of theory and operating principles. Tran moves quickly between frameworks of pedagogy, institutions, public health, and philosophy. The book is worth reading simply for the words she explores. Phronesis (wisdom that attends to lived experiences, is transformative and change-seeking, and always interprets the lived context in light of the values and virtues of the sacred tradition) and thanatourism (a carnival of cruelty that involves voyeurism into the pain of others) were two of my favorites.

I was drawn into Tran’s vivid portraits of what the church is and what she thinks it could be. What churches are, she posits, are spaces where violence is potentially taught and sacralized:

What if, instead of being communities of good news, Christian faith communities are actually communities plagued by these enduring forms of violence? What if the enterprise of religious formation is being forged by a pervasive curriculum of violence, implemented through a variety of sacralized, oppressive pedagogies, as we continue to deny or fail to recognize the insidiousness of our complicity in intersecting repressive structures throughout history and contemporary society? What if many Christian churches are not just dying institutions but also toxic communities that actively emit symptoms of violence?

Tran’s vision for what the church could be involves “ecstasy,” “reenchantment,” and “resacralization.” She foresees a future in which “white Christian communities garner the courage to transgress racial barriers because they recognize that such work saves not the lives of people of color but rather their very own white lives.”

As a pastor in a largely white Episcopal church, I wanted to jump up and pump my fist and be worthy. Yes! Yes! I would buy the whole box set of whatever she was selling! Show me how to do it!

But what makes Reset the Heart a glorious read is also what makes it frustrating: it is written in the midst of things. It’s an active and thorough assessment of a situation in play, but what to do in response is being developed as the boat careens. Tran’s solution set is thin compared to her diagnosis.

What Tran offers is a start. She suggests that Christian education—by which she means general formation and discipleship rather than the teaching of any particular group—must be an experiential learning that takes place through eating, praying, and loving with others—sometimes very others. By engaging in these activities in a faithful way, we are changed—not merely through contact with those who differ from us but also through seeing examples of discipleship in new ways and following suit, what she calls “positive mimicry.” From these encounters, we can develop the ability and freedom to imagine a more just future for ourselves as Christians and as citizens.

Tran interweaves her discussion of eating, loving, and praying together with examples from St. Louis area clergy. These stories are real and humble. I wanted a grand fix. What I got was candid reflection on small, uncomfortable acts of being together that often yielded mixed results. Intrachurch meals and Bible studies, attending protests, and engaging in social justice initiatives are more potent when accompanied by theological reflection, but even then they’re hard to sustain in a community. Tran bravely engages in the very pedestrian space where theory meets practice.

Tran’s brilliance is in observing and diagnosing what is happening in the church, calling for action as opposed to stultifying fear. She provides a shape to hope and inspires the desire to act. The modesty of her case studies made me think, “Well, heck, we can do that,” which is motivation toward action. In this sense, Tran succeeds heroically.