Is Christian celebrity harmful to the church?

Yes, says Katelyn Beaty, who defines celebrity as “fame’s shinier, slightly obnoxious cousin.”

When I was a child, my mom watched Joel Osteen’s sermons on television and filled our bookcases with his books. Our church regularly participated in Willow Creek’s Global Leadership Summit before being absorbed into a network of Indiana megachurches. I came to idolize women like Jordan Lee Dooley and Annie F. Downs for being good Christian role models on social media. This is precisely the world journalist Katelyn Beaty aims to expose in her new book, an examination and critique of Christian celebrity.

Beaty dives into stories of high-profile Christian pastors, influencers, authors, and megachurch organizations to craft the argument that celebrity ultimately hurts rather than helps the church. Inspired by the dramatic fall of Christian leaders such as Mark Driscoll, Bill Hybels, and Carl Lentz, she outlines the ways celebrity sabotages true Christian leadership. She examines how Christians have wielded celebrity as a tool to expand their reach in the world, and she calls for an alternative: a life of ordinary faithfulness, rooted in a theology derived from Jesus’ upside-down kingdom.

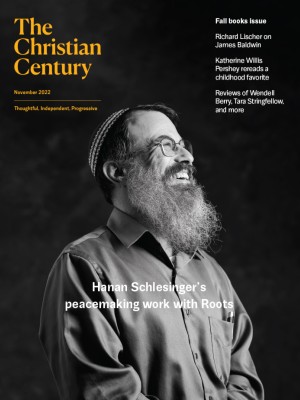

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Latin root of the word celebrity evokes fame, but Beaty notes that there are differences between fame and celebrity. Fame involves being known by far more people than you could ever know yourself, but it is not always deliberately sought. For instance, Rosa Parks was an ordinary person who became famous for doing a seemingly ordinary thing. In a meritocratic culture like that of the United States, fame is often awarded to those with humble beginnings whose talents have made life more enjoyable, such as Walt Disney or Steve Jobs. Fame is not sinful in and of itself, Beaty claims, and not all famous people should be written off as shallow and inauthentic.

Celebrity is “fame’s shinier, slightly obnoxious cousin.” Beaty defines it as “social power without proximity.” It utilizes mass media to give viewers illusions of intimacy with a well-known person in order to promote the entertainment industry and consumerism. Beaty cites historian Daniel Boorstin’s observation that celebrities are created by those around them—those who read about them, watch them on television, buy recordings of them, and talk about them to their friends.

Power is the how and the why behind Beaty’s thesis that celebrity corrupts. Properly understood, power is “the innate human ability to steward the world to glorify God and bless creation and fellow image bearers.” All human beings are icons, representations of God’s image. Celebrity is dangerous because it makes humans into idols, placing them above God. Beaty reminds readers throughout the book that with great power comes great responsibility. When we start to believe we wouldn’t ever abuse the power we have been given, we are already in grave danger. Driscoll is a salient example of how power can be wielded abusively in the name of God. He was frequently praised by major Christian organizations despite his reputation for being a bully, Beaty notes.

Beaty observes that celebrity corrupts in four ways: it attracts, deceives, shields, and isolates. People are attracted to the idea of being invited into a celebrity’s inner circle, however briefly. Celebrities are deceived to believe that they operate outside of “normal bounds of integrity and accountability.” When allegations of abuse are brought forward, celebrities are shielded by the unwavering loyalty of fans, who often presume their innocence. This shield both protects and isolates. Removed from true proximity and authentic relationship, the celebrity finds it nearly impossible to be truly known, seen, and loved.

One of the book’s most important points is about the contemporary evangelical movement’s outsized utilization of celebrity as a tool for conversion. Billy Graham was one of the first people to do this. Applying salesman-like charisma to his preaching, he traveled around the world on evangelizing “crusades,” utilizing the new tools of mass media to become a radio and television personality. Describing preachers like Graham, Beaty says that “the chance to save more souls justified the use of whatever tools were at their disposal.” Graham’s style of ministry demonstrates one of Beaty’s primary concerns: the individual pastor being held above the institution. Graham’s powerful preaching is what attracted people, rather than the desire to belong to a local church community.

Beaty levels this same charge against megachurches: in elevating the lead pastor to celebrity status, they diminish the power of the church as an institution. Willow Creek became one of the most influential megachurch networks in the country by selling its ministry model and celebrity pastor approach to other churches. Hybels became the centerpoint of the church, and when credible allegations of sexual assault were made against him, the community was left not knowing where to turn.

Additionally, Beaty argues, the contemporary evangelical movement uses Christian celebrities as pawns in the culture wars. The public conversion experiences of Christian celebrities like Kanye West and Justin Bieber, for instance, make Christianity relevant to secular culture. “If the religious right aligned itself with powerful politicians to protect the faith in the halls of Congress, then evangelical leaders aligning with celebrity Christians is a grasping for ‘the soft power of Hollywood,’” she writes, citing journalist Laura Turner.

What Beaty’s analysis neglects is the fact that contemporary evangelicalism uses Christian celebrity specifically to garner support for conservative political causes. If glamorous churches and pastors are showing off the ideal of meritocracy in the United States, then shouldn’t their fans vote for the politicians who claim to support those same values? With more attention to the politics of celebrity, Beaty’s book would be more than merely an introduction to the Christian celebrity phenomenon: it would be a significant resource for those looking to understand and de-radicalize the religious right.

Beaty’s final plea is for her readers to take up lives of ordinary faithfulness. Celebrity is “a worldly form of power and evaluation of human worth,” and the moment it is used for the purpose of sharing the gospel, the project of the gospel changes. The life and ministry of Jesus, according to Beaty, run contrary to the values and temptations of Christian celebrity. “How we do the kingdom things matters,” she writes. In other words, we cannot do good things like spreading the gospel using a bad tool like celebrity.