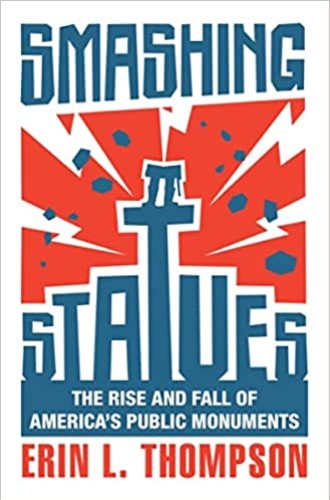

The American tradition of tearing down statues

Public monuments hold power. So does their destruction, says historian Erin Thompson.

In summer 2020, the United States experienced a nationwide reckoning with its racist past, ignited by the police murder of George Floyd and often centered on the symbols enshrined in our memorial landscape. Across the country, activists tore down about 35 monuments to controversial figures, including Confederate leaders and soldiers. Another 130 monuments were taken down through official channels. President Donald Trump retaliated by signing Executive Order 13933, instructing federal law enforcement to prosecute anyone caught damaging federal monuments or statues. “Long prison terms for these lawless acts against our Great Country!” Trump tweeted shortly after the signing.

To judge by the former president’s fuming response, one might conclude that tearing down statues is a deeply un-American deed, an act of treason against public memory. However, legal scholar and art historian Erin L. Thompson thoughtfully and astutely discredits that notion. In fact, according to Thompson, the nation was forged in the destruction of historical symbols.

Smashing Statues opens during another sweltering summer: 1776, just days after the Second Continental Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence. Following a public reading of the document in New York City, a crowd of average citizens and Continental Army volunteers, buoyed by their discovery of their “inalienable Rights” to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” tore down a gilded statue of England’s King George III. After yanking the figure from its base, the crowd chopped it apart with axes. One protester even put a bullet through the downed monarch’s head.