Boys will be like the boys they read about

Books can’t singlehandedly destroy toxic masculinity. But they can chip away at it.

When I hear “boys will be boys” arguments, I’m never sure what the phrase is supposed to mean. Boys will be mischievous? Entitled? Filled with pent-up energy that can only be released through physical exertion—whether playing football, wrestling on the floor with a sibling, or pinning down a girl on a bed and covering her mouth while groping her against her will?

I’m skeptical of the gender essentialism and binary presumptions behind the claim that boys will be boys. But my deeper problem with the phrase is that it’s almost always uttered in a situation that involves bad behavior—and done so with a sense of resignation. We don’t say “boys will be boys” when we’re congratulating a boy for his artistic ability or interest in linguistics or safe driving skills. And responding to boys’ misogynistic behavior with resignation (or a wink) means being equally resigned to a corollary for girls: girls will be mistreated, assaulted, patronized, and disrespected. Not because there’s a war between the sexes, but because our culture conditions boys to adopt attitudes and behavior that objectify women and girls.

One alternative to resignation is to be deliberate about countering the culture of misogyny that shapes our children. As the #MeToo movement gained momentum, I noticed a preponderance of new children’s books that I was excited to read to my daughters. Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls, She Persisted and She Persisted Around the World, I Dissent, This Little Trailblazer, What Would She Do?, and Dear Girl all now grace our bookshelves. What these books have in common is that they seek to empower young girls (and perhaps also children who aren’t girls) by instilling in them a sense of confidence and agency while being realistic about the challenges girls and women face.

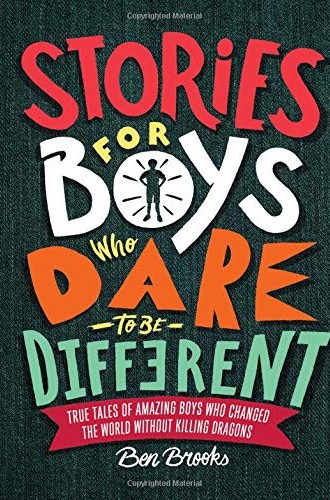

I’m fairly certain that if I had sons, I’d want them to read all of these books. But I’d also want them to have books that celebrate boys and men who resist cultural presumptions about masculinity. As beautiful as my feminist children’s books are, they don’t lift up models of healthy, brave, gender-defying boys and men. I hadn’t noticed that fact until a new children’s book came across my desk: Stories for Boys Who Dare to Be Different: True Tales of Amazing Boys Who Changed the World Without Killing Dragons. There are a few soldiers profiled in the book, but there are also painters, musicians, and makeup artists. There are some athletes, but several of them have physical disabilities or face other challenges. There’s an NFL quarterback, but he happens to be a feminist. As the author, Ben Brooks, puts it,

Instead of playing football, Don [McPherson] now travels the country, talking to young people about masculinity, feminism, and sports. Especially in sports, he thinks that men often think and talk about women in negative ways, and that thinking and talking has consequences. Girls often stop playing sports at school because they’ve lost their confidence. Right now, all across the world, women are feeling unsafe because of how they’re treated by men.

Don believes that the way to end this isn’t just to treat women better ourselves, but to stand up and say something when we see people who aren’t.

The heroes of this book demonstrate that there are many ways of being masculine: fighting against apartheid or child slavery, designing houses, struggling to flourish amid anxiety or depression, embracing a gender identity or sexual orientation that doesn’t conform to social norms, doing math, dancing, standing up against oppressive institutions, being an advocate for the environment, inventing a new language, sacrificing comfort for the sake of the common good, writing poetry or fiction, crying, embracing nonviolence, treating people with kindness.

Boys—and all other children—will be what their culture sets them up to be. That’s why when my nephew was a toddler, I bought him a doll for Christmas after hearing his dad tell him that boys don’t wear pink. (I wish Pink is for Boys had been in publication at the time. Its whimsical, inclusive illustrations and simple but funny text challenge gender rigidity in a disarming way.) A few months later, I asked my sister whether my nephew played with the doll. “He just drags it around by its hair,” she responded. “Maybe that’s because you refer to her as it,” was my reply.

No single book or gift will change the culture our children inherit. That’s the work of all the little—and sometimes big—decisions we make over the course of a lifetime: how we talk with children about gender, which role models we hold up for them, what books we read to them, which pronouns we use for God, how much we encourage them in sports and music and dance and reading and math, and thousands of other choices.

My nephew just turned 13. Even though he grew up believing pink was for girls and never cuddled with a doll, he has grown into a respectful, unassuming teenager. This gives me hope that we’re on the right track, that the children who come of age in the #MeToo era just might be wiser in discerning the shortcomings of the culture they’ve inherited than those who have handed it down to them. My nephew is a bit old for Stories for Boys Who Dare to Be Different, which is written for the 9-12 age range. But I’m still going to give it to him for Christmas this year. Maybe he’ll read it to his younger sister and brother.