Sin is about not knowing who we are

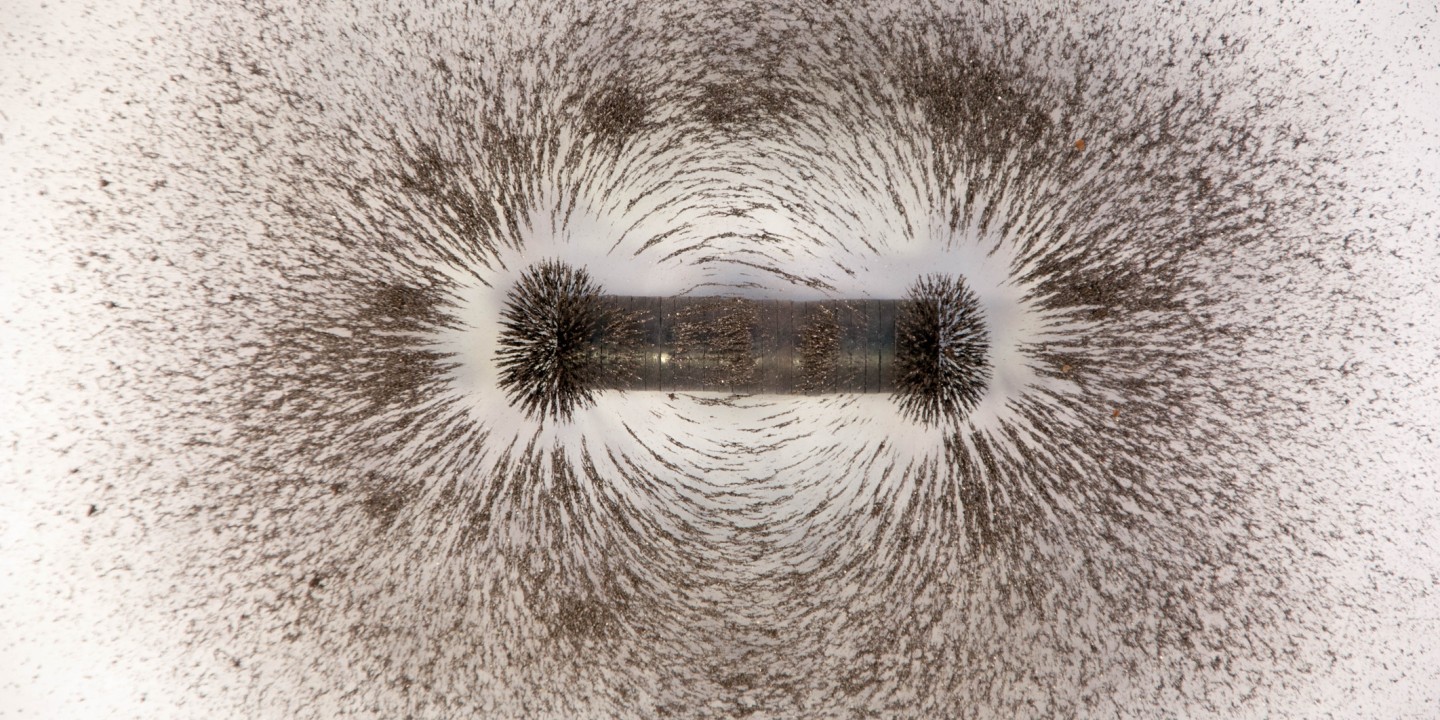

Mystics understand what moralists do not: God pulls us like a magnet to our essence.

Few theological concepts are as mangled and misinterpreted as the concept of sin. Yet we find the subject off-putting. We don’t understand it well because we prefer not to discuss it. Growing up, many of us accrued the wrong notion that sin involves moral peccadillos one commits personally, often having to do with sex or what one consumes. And we were told the Christian life is about achieving moral purity, ascending the ranks of Good Christians by ridding our lives of sins, while simultaneously clinging to sacrificial-atonement Jesus as insurance because “we all have sinned.” Despite its mainstream popularity for the past few hundred years, this circular, simplistic concept is almost too ridiculous to warrant comment.

According to much New Testament teaching and centuries of thoughtful Christian theology, the understanding of sin as moral peccadillos is misleading. This use of sin is found in the tradition and was the view emphasized by moralists throughout the centuries. But a more complete theological view sees moral missteps as symptoms of a disease of the soul, not at all the disease itself. And according to the teachings of Paul especially, sins as moral peccadillos can be quite useful (one reason I like him, despite all). In the way physical symptoms let us know something is off in the body, moral missteps assist us if we pay attention.

The fuller, deeper meaning of sin has to do separation or disconnection from our true identity. Sin is about not knowing who we are. Essentially, sin is a state characterized by being unconscious that we are united with God, that we are imbued with God, that we are one with the ground of all being. We are each and every one a little epiphany, a manifestation of God in creation. When we do not understand this, we operate out of ego and self-protection. And ego and self-protection cause us to make many missteps. But focusing on the missteps misses the point, keeping us fixated on achievement or participation in petty purity contests—when instead we have been invited to a divine, familial love feast.

Sin in the theological sense involves living out of this illusion, this state of separateness—meaning separateness from God, from others, and from the entire created order. Meanwhile God is constantly revealing to us our inherent union, drawing us across the chasm of separation back to our identity of oneness. The mystics always got it, while the moralists misunderstood. In fact, you could say God is constantly pulling us like a magnet back to our essence. I recently heard someone describe God as an attracting field of love. How stunning and beautiful! How much more life-giving than the destructive notions of God as a disappointed father or fastidious schoolmarm ready to rap our knuckles for our moral slip-ups.

The task of spiritual practice, then, is to facilitate the recognition of who we are in God, to awaken us to what is already there, to recognition and surrender to the attraction of this alluring Love—that we might return to our trues selves as a part of it. The invitation is ultimately to incarnate God in our own small corners of the world. This is a prominent interpretation of the theological concept of Christ, to become the body of Christ here and now.

This participatory reality is open to all souls, whatever their spiritual or religious persuasion. When we truly allow and participate with the presence of God in us, in our worlds, we become a part of the body of Christ—which is to say, the incarnation of God that emanates throughout all of creation. The Christ was present from the dawn of creation. In his total willingness and openness, Jesus the human being showed us the way, showed us how to fully be “the Christ”; and according to Christian tradition, in Jesus we can see and hear and touch the reality of “God with us.” But the Christ existed prior to Jesus, and is not synonymous with him. The Universal Christ is much broader, and invites the participation of each one of us.

The task of spiritual practice is to come to recognize this. But it also inspires day-by-day recognition of the wrong-headed ways we typically identify ourselves. Recognizing our wrong-headedness is, however, not about self-flagellating or viewing ourselves as less than. In fact, coming again and again to see the false self (and remember, the Apostle Paul says “thank you” to sins for helping us do that!) is what reminds us that we are actually so much more than. Seeing our false selves allows us to re-cognize (or “know again”) our true selves in God. This is why Christianity isn’t a recipe for making our lives moralistically pure and pretty and faultless. In fact, if there was ever a doomed and misdirected venture, it is coming to Christianity because we want order in our lives and the lives of loved ones, to achieve moralistic benchmarks while stewing in judgment of others. This is like asking for more of the disease in hopes of curing our symptoms.

The Greek word translated sin (hamartia) means “to miss the mark.” But we have misunderstood this to mean falling short morally, or not being good enough. That’s a tragic misunderstanding of sin. Sin as missing the mark is actually saying: You think you are X, but look! You are actually Y. You think you are a self-guarding, separate entity journeying through your life—with no choice but to look out for Number One, but this misses the mark. The stunning fact of the matter is that you are so much more than this; you are fully a piece of God journeying through this world. The purpose of your life is to come to realize it.

Perhaps this is why failure is so key to growth in the spiritual life, because failure is often the only thing strong enough to break the illusions of the ego. Often failure wakes us up, helping us to confront the loneliness we feel in our self-imposed exile from God and others, making us long for home. And if this is true, if we actually encounter who we are by falling into divine mercy and embrace, then we can stop trying so hard to be right and pure. If we fail and fall it is not the end of the world. In fact, it may just be the beginning.

That said, our moral missteps do often hurt people, and our collective sins in aggregate lead to institutional oppressions such as poverty, cultures of harassment, racism, and destruction of the environment we share with fellow creatures. So sins aren’t to be taken lightly or brushed off. Instead we can stay awake to what they can teach us, acknowledging our homesickness and loneliness, our self-imposed exile, recognizing the ways we have chosen flank-guarding and ego-stroking—not just individually, but as a society—instead of our destiny of union with the Field of Love.

In response, as we prepare for Lent, may we have minds expansive enough to see who we really are, all the ways we deny ourselves this glorious identity, and to see we are invited to a love feast—our charmed and joy-filled destiny as children of God.

Originally posted at Brown’s blog