Reclaiming the E word

Evangelism has become a dirty word among progressive Christians. But don’t we have good news to share?

It’s hard to say the word without provoking nervous laughter. Or a sanctuary full of frowns and flinches. It’s progressive Christianity’s big, bad E word: evangelism.

Having grown up in a faith tradition that not only encouraged me to share the gospel but insisted that I do so (lest my nonbelieving friends end up in hell), I’m struck by the irony. Progressive churches tout beautiful, attractive values: inclusiveness, hospitality, diversity, openness. And yet we rarely invite. We cringe from invitation like cats from bathtubs.

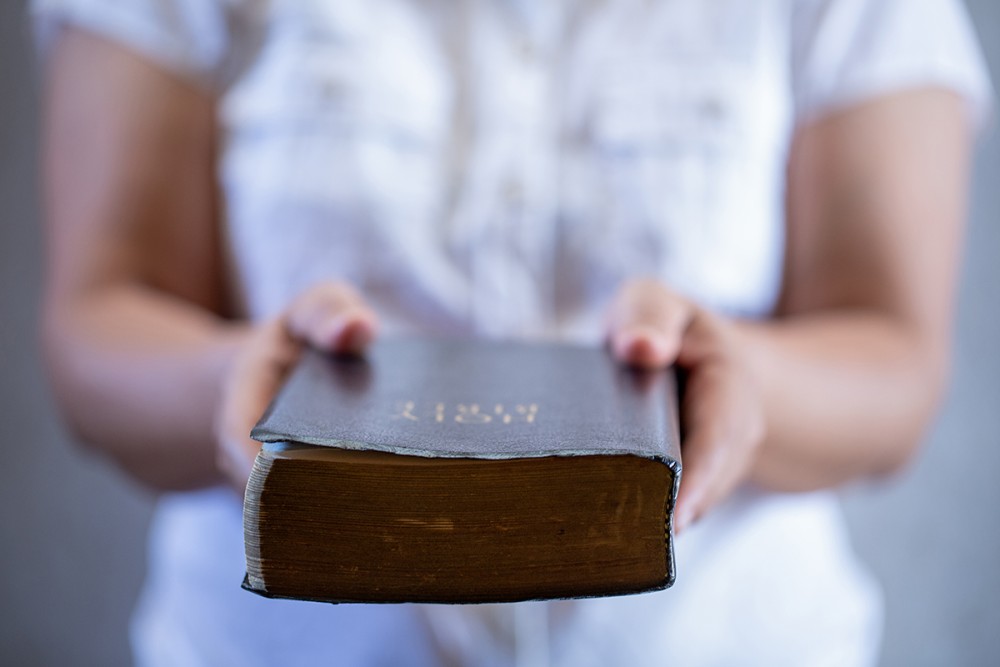

I know that we have good reasons for doing so. We don’t want to repeat the horrific sins of colonialist Christianity. We don’t want to come across as judgmental or obtrusive. We don’t want to be associated with fundamentalist Bible-thumpers. We don’t believe that the gospel is about securing fire insurance from eternal damnation. We don’t believe that we hold a monopoly on spiritual meaning, wisdom, and truth. We don’t wish to come across as false in our relationships, feigning love and care in order to manipulate people into signing on a doctrinal dotted line.