In response to our request for essays on “window,” we received many compelling reflections. Below is a selection. The next two topics for reader submissions are Scrap and Threshold—read more.

One day in 2009, my father called to tell my husband and me about a dream he had. “I was in a house full of people. Everyone there was so happy, and I was happy too,” he said. “I looked out the window, and I saw you both. And then I looked down, and I was holding a baby.”

What he didn’t know is that I was pregnant, but just barely; we hadn’t told our families yet. A few weeks later, we called him back. “Dad,” we said, “your dream is going to come true.”

But he never held our baby. My father, 54 years old, died of a heart attack one month to the day before his first grandchild was born. Dad’s dream seemed like a cruel tease, a premonition that seemed entirely plausible until it was torn away.

When Dad first described his dream we had focused, naturally, on the baby. But what if, instead, the message of the dream was the window: a transparent barrier that separated him from us, through which he could see but not be seen, a happy room in another place?

I have preached at length about the power of myth and stories, but I want my dad’s dream to be real, not metaphorically real. I yearn to believe there was a time—after his death and before her birth, perhaps—when he held my baby, on the other side of a window. I want him to feel that glow of eternal joy, that crowded mansion in our Father’s house. I want to know that he’s gotten to be a grandad, even if in a distant kingdom.

But I don’t know; none of us can. From this side, the window’s opaque. At its best, it’s frosted glass, showing only shapes and shadows, and yet letting through light.

My father spent his career working with glass. He was a camera lens designer, and he practiced bending light to capture images. On his footstone at the cemetery we put 1 Corinthians 13:12: “Now we see through a glass, through a window. But one day, we’ll see face to face.”

Liddy Barlow

Pittsburgh, PA

“Mom! Where are you going? Mom! Where are they taking you? Mom?” The words of my 12-year-old son were muffled as the officer opened the back door of the cruiser. I bent down, navigating myself into the car with my hands cuffed behind my back. Pulling away from the house, I could make out Daniel’s face in the early evening light, pressed against the screen of his open bedroom window. He was sobbing.

Once they booked me, they did not put me in a cell for several hours. I was not, they said, their usual customer. I was still wearing the lilac gingham capri pants and matching sleeveless top I had changed into at the church after preaching that morning, before walking in the hunger walk. When they finally let me use the phone, I called my neighbor. Would she check on my kids? Would she tell Daniel I was all right—that I was thinking of this as an adventure?

I called her back a little later. She hadn’t talked to Daniel; she would have had to speak with him through his window, and her husband felt it was unsafe for her to do so. My older son was in the driveway, using a sledgehammer to destroy some cinder blocks. She could see and hear him from her backyard two houses down.

The officers who had been to our home recognized this sham for what it was. But their hands were as tied by state law as mine had been in those cuffs. I was divorcing my husband of 19 years after finally realizing I was not the only family member suffering from his untreated mental illness. Desperate, he decided to demand the house, full custody of the boys, and alimony. Then he accused me of hurting him—believing, in his twisted logic, that this would bolster his case.

Eventually, they ushered me into a little room where I removed my bra and shoes. From there, an officer put me in a cell. The walls were thick and gray. The only window was a 12-inch square in the heavy metal door.

At some point in the night, I fell asleep. I had no idea what time it was when I awakened. The fluorescent lights in the cell and through the tiny window in the door were the same shade of bright as they had been when I dozed off.

Time passed. I began to wonder if they’d forgotten me in that cell. What if, after the shift change, no one remembered I was there? I had been hungry for a long time. All I could see through the window was a square of relentless light.

Eighteen years later, I went back to jail—this time to visit women there as a pastor. “Do a Bible study,” a colleague had urged me. “Listen to their stories. Bring them a little hope. It doesn’t have to be anything formal or fancy.”

The third time I visited, it had snowed that first lovely snowfall of the season, when people are still excited by the crisp white beauty of it all. My cheeks and the tip of my nose were red as I brushed big wet snowflakes out of my hair before the women came into the conference room. They wore hot pink T-shirts and hot pink sweat shorts. They had bare feet inside orange Crocs. I laughingly exclaimed, “Brr . . . you make me cold looking at you. It’s snowing!”

We didn’t know, said the women. We don’t have a window.

I remembered.

Rebecca Zahller McNeil

Trinidad, CO

In sixth grade, I realized that I was bad at math. It was one of those realities that took a few months to fully sink in. There were the homework assignments that never seemed to make sense. There were boring lessons that neither piqued my interest nor engaged my memory. Finally, there was the test that I couldn’t finish because my brain got swallowed whole by a single long division problem that refused to be solved. I still remember my pencil marks covering the entire test page and my attention wavering as more and more kids got up and left and the next class started to file in.

The teacher was kind, and that made it worse. If even her kindness and offers of generous support couldn’t render long division comprehensible, I was surely beyond all hope.

Sixth-grade math was located on the second floor of the middle school building. The classroom included a line of windows which gave me a view of the schoolyard with a tree in the middle. I didn’t know what kind of tree it was, but it had long trailing branches. I didn’t pay much attention to it in the beginning. I often stared out the window, but the view was unremarkable.

When March moved into April, I watched day by day as bare branches on that tree budded into a riot of pink blossoms pouring down from the tree’s top all the way to the ground. I could scarcely take my eyes away from that window. The tree, its branches drenched in pink and swaying in the April breeze, held my entire attention. Was x somehow equaling y? What about dead branches somehow becoming a living waterfall of color?

Miraculously I didn’t end up repeating sixth-grade math. At some point along the way, I made enough sense of x and y to pass and then upgraded to the kind of math that lets you use a calculator.

I am grateful to that sublimely patient teacher for somehow getting me through her class. But I am even more grateful to that window and the view of that tree.

Emily Olsen

Beaverton, MI

As we worked on our new church building, we got to the design stage of a bold, rather modern-looking, circular stained-glass window.

We agreed that the text for this rose window would be Revelation 22: “Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb, through the middle of the street of the city.” As the artist created designs, we were all thrilled with the colorful window that would reflect light all through the sanctuary of that city church.

Here is what we could not agree on: Should the river be flowing vertically, from the top of the window toward the bottom? Or should the window be oriented so the river of life was coming from left to right, moving horizontally?

The debate went on meeting after meeting. It was a big deal to us, and those on each side of the issue had good reasons for their position. I myself argued with conviction and made theological references. It was intense enough that there were sidebar conversations in the hallway and parking lot. More than a few of us wondered if this artistic conflict would pull us apart. Some of us had known one another for nearly 20 years, and yet we could feel this disagreement threatening to unravel us.

Several months ago I returned to that congregation to preach. I entered the sanctuary, soaked up the beauty of the place, and looked up at the window. For the life of me, I could not remember which position I had taken on the orientation of the window.

How many holy, deep moments, how many things of kingdom consequence, did I miss as I chased issues, decisions, and projects that didn’t really matter all that much?

As worshipers gathered and the church staff buzzed around preparing for worship, I offered my private prayer of confession to God for the times when I turned little things into big things. It can sometimes take years for the angels to show us the river of life.

Mark Fenstermacher

Auburn, IN

From Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking:

If you look at a window, you see fly-specks, dust, the crack where Junior's Frisbie hit it. If you look through a window, you see the world beyond. Something like this is the difference between those who see the Bible as a Holy Bore and those who see it as the Word of God.

Scraping paint from our garage window, I felt overwhelmed by everything that needed doing. We had small children, and I pastored a rural church. In a couple hours, I was to give a Christian education workshop and then go on retreat. Frustration seeped into my brain, and I plunged my fist through the glass.

I cleaned up the debris, showered, changed into good clothes and a tie, and then drove to a high school gym to teach Sunday school teachers about how prayer helps with stress.

Later I drove to Henri Nouwen’s house for a guided retreat. I found my room, welcomed by a warm note from Henri and a vase of bright sunflowers—among his favorites.

We met twice daily for an hour to discuss scriptures that he assigned for meditation, insisting I use his Jerusalem Bible.

All week I struggled with whether to tell him about that window, so ridiculous and humiliating. I evasively summarized being “overloaded.” I couldn’t bear to confess, even when he said, “Our time together will be helpful only if you are completely honest.” Henri told me that I needed to make my ministry “more eucharistic.” I had no idea what he meant. He gave me a manuscript of his forthcoming With Burning Hearts. Reading it, I learned that Jesus takes, blesses, breaks, and gives us into ministry.

At the end of Thursday’s breakfast, Henri stood and said, “I need to make a quick phone call.” He paused and asked, “Can you clean these for me?” He gestured toward two simple glass candleholders on the counter, streaked by drips of wax.

One at a time, I held each over the garbage bin; with a butter knife I scraped away wax chunks. Then I filled the dishpan with warm water and immersed one, scrubbing and setting it aside on a towel, then the other.

When I set the second one on the towel, I was shocked to see cracks in it. Were those fractures there before? Surely I would have noticed? Is this how I repay Henri’s hospitality?

Cheryl, a community assistant, wandered past. “Look,” I said. “One cracked. I don’t know how. But they’re pretty simple. They can’t be worth much.”

“Unfortunately, they are. A famous Vermont glassblower custom-made them for Henri.”

My stomach tightened with worry. Minutes later, he burst into the kitchen, hurrying.

“Wait, Henri, I have to show you something. I’m not sure what happened. A holder cracked. I’m sorry. I thought I was careful.”

He grew still, in a rush no longer, and studied the damage. I waited, fretting. Would he scold me over its value, specialness, uniqueness? Would he lament the loss? Would this ruin—end—my visit, future visits? Would he ask, as my father so often did, “What’s wrong with you?”

“Oh, Artur,” he said; with his accent, like my father’s, he always mispronounced my name. “Don’t worry.” His long arms swept me into a bear hug, tight against his chest, full body contact. I could count each bony finger pressed into my back. Then he released me and noisily bounced down the wooden steps to the chapel.

When I entered the chapel for mass, I saw the candleholders, now bearing lit tapers, at either end of the altar. I could no longer see where that break might be.

Arthur Boers

Bracebridge, ON

It was dark outside, not yet dawn. The rain was pelting down as I grabbed my bag of clothes and leftovers and dashed through the ferocious wind to my little Honda. I had made the Minnesota to South Dakota drive only two days earlier to spend Thanksgiving with my daughter and her family. Every moment with them had been a joy, but now I needed to get back home and I would have to drive through a storm to do it. I hunkered down, gripping the wheel and staring at the road as if my effort could make the rain stop, the wind cease, and dawn arrive.

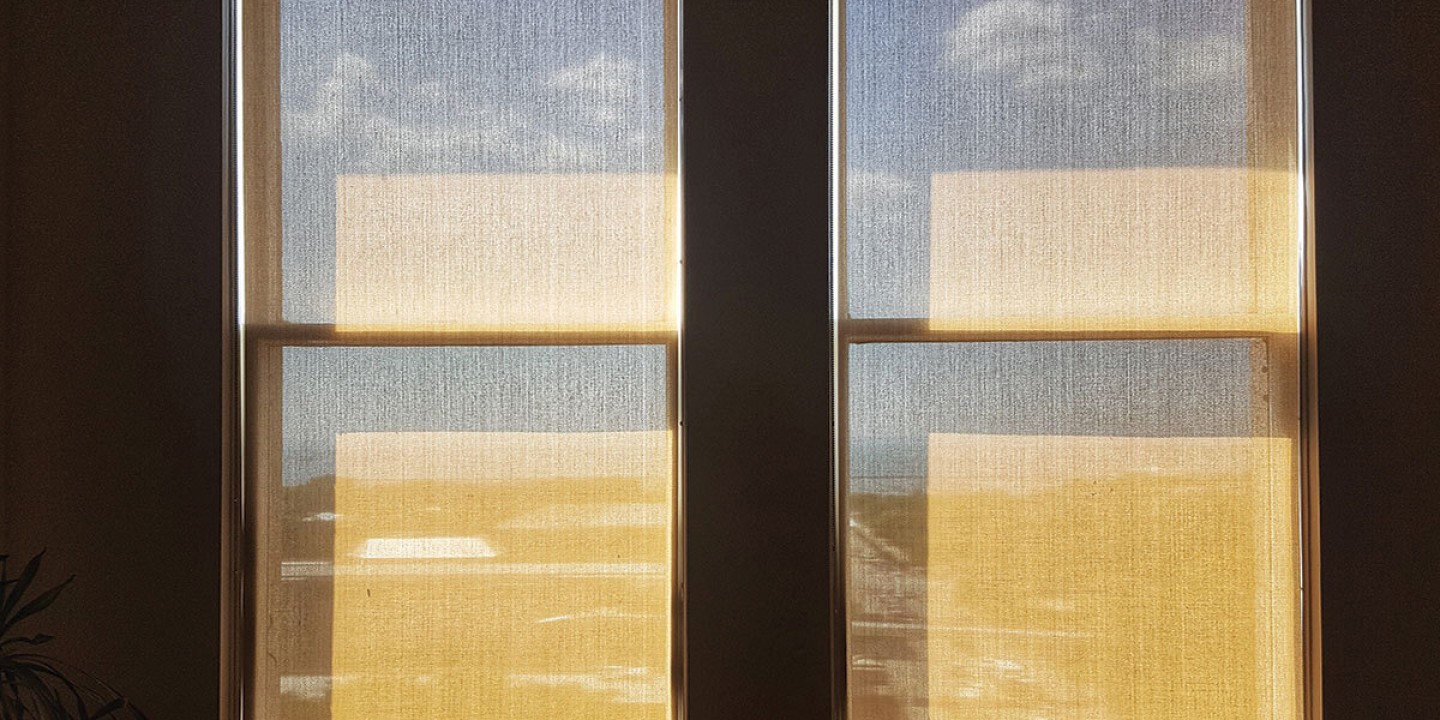

After Rapid City, the downpour lessened as the black clouds shifted, the center spreading apart to form a window. I can still close my eyes and feel myself being pulled into the bright dawn beyond. Instead of the rising sun I saw its gleam upon cumulus clouds, like a city hidden there. I quickly veered onto the shoulder to watch the golden shapes. The window was soon curtained again, concealing the radiance.

Now, near my window at home, a tiny vase holds sprigs of tumbleweed I found bouncing across the freeway like terrified rabbits—my souvenir of a promise of light beyond any darkness.

Kristin D. Anderson

Roseville, MN