Telling the truth about racism

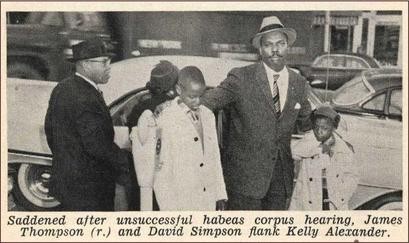

The story of James Thompson and David Simpson is one of many that cry out for an acknowledgment of wrongs done.

It all began with a childhood dare. The end result was shattered lives.

In October 1958, two African American boys in Monroe, North Carolina—James Thompson, age nine, and David Simpson, seven—were playing with friends in the white neighborhood where James’s mother was a domestic housekeeper.

Decades later, in a StoryCorps interview that aired on NPR, Thompson described the moment: “One of the little kids suggested that one of the little white girls give us a kiss on the jaw. The little girl gave me a peck on the cheek, and then she kissed David on the cheek. So, we didn’t think nothing of it. We were just little kids.”