Why I’m not participating in this weekend’s Faith and Blue event for churches and police

The problem isn’t police-community relations. It’s our acceptance of a broken system.

Like thousands of my colleagues across the country, I recently received a letter from an organization called Faith and Blue. I was encouraged to participate in the National Faith and Blue Weekend, October 9–12, an event dedicated to “facilitate safer, stronger, and more just and unified communities by facilitating collaborations between officers and local residents through the connections of houses of worship.”’

As the pastor of a Mennonite church, I suspect I read the letter from Faith and Blue from a different theological vantage point than many of my colleagues. As part of the Anabaptist tradition, Mennonites recognize that we live within a world of competing loyalties. But our sole allegiance is to Jesus Christ, God who came in the body of a member of an ethnic minority and was murdered by the state. Because of this, we do not take oaths, and we don’t participate in institutions like policing and the military, institutions that ask us to enact state violence on people made in the image of God.

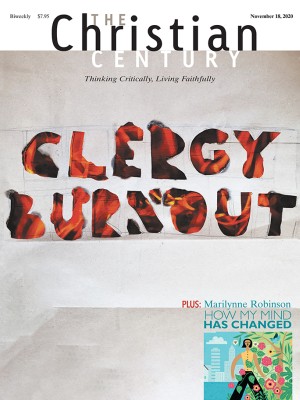

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It is an absurd and radical conviction, and it has a history of getting us killed. When Anabaptists refused to participate in the First World War, a group of them were thrown into a military prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. Two of these men—the Hofer brothers, who were Hutterites—were refused water and thrown naked into a freezing cellar. For days their hands were tied to rods above their heads with their feet barely touching the ground. Eventually they died from this torture, American citizens in an American military prison.

Despite this history, Mennonites are people called to peace and reconciliation. And that is language that the people behind Faith and Blue understand. The letter and the group’s website brim with calls for bridge building and an end to bias. They suggest relational connections built over meals and in dialogue. They plead for unity marches with police and prayer vigils for officers.

The same day I received the Faith and Blue letter, the Raleigh News and Observer reported on the release of police body camera footage from protests in my city following the death of George Floyd. We already knew that officers in riot gear deployed expired tear gas against protesters who threw rocks at them. Now there is footage of police shooting the canisters directly at protesters.

In footage from another camera, an officer in an armored vehicle remarks, “As much as I love chasing people down on foot, it’s so much fun watching them run when we’re in the gator.”

“They just fucking fall and shit,” another jokes.

Officers laugh together after one of them says, “I’m going to say we grab at least three more people tonight.” They denigrate protesters and call them names.

The footage shows other officers assisting protesters, in one case helping a man with glass in his hand. And moments like these are sure to fuel the both-sides-ism many people appeal to in response to protests against policing across the country.

Faith and Blue, after all, is not asking clergy to become educated on the long history of police brutality and failed reforms or to support policy changes proposed by members of impacted communities. Instead, the group calls for churches to cushion the blow of police brutality—and to help clean up officers’ public image.

This is not a new strategy. In 1963, sitting in Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King Jr. penned a letter to white religious leaders, excoriating them for their tolerance and acceptance of policing tactics used against the civil rights movement. Near the end of the letter, published in these pages, King writes:

You warmly commended the Birmingham police force for keeping “order” and “preventing violence.” I doubt that you would have so warmly commended the police force if you had seen its angry dogs sinking their teeth into six unarmed, nonviolent Negroes.

Just a generation later, the church—and especially White moderate churches—was already whitewashing the civil rights movement. But as Kwame Ture once pointed out, King did not pin the atrocities of racism on notorious individual cops like Bull Connor but on “the entire policy of the United States government.”

Because of this, King’s tactics were considered inflammatory. He was accused of inciting violence, told he was advancing a radical agenda and pushing it too fast. A 1968 Harris Poll reveals King achieved a 75 percent disapproval rating.

Faith and Blue provides opportunities to share mission statements and eat hot dogs with the police, to play football and to ask questions about the impact of the group’s efforts on cities. But the crisis it purports to address will not be solved with stories or picnics. Solving it requires policy makers, churches, and others to align themselves with a different vision for safety and community care, led by the communities most deeply impacted by the justice system.

The problem in this moment is not a failure to see that there are both good and bad police officers. It is not that Black people aren’t familiar with their local beat cop. It is not that the call for abolition is too fast, too aggressive, or too polarizing.

The problem is our acceptance of a broken system.

We people of faith are once again in a moment at which we will be asked to choose what kind of love we offer to the world. Will it be conflict avoidance that projects equal measures of blame on police and on people of color? Or is it time, finally, to demand a new world, to put ourselves in the service of those who work toward a social order without the birth-to-prison pipeline, without the criminalization of homelessness and sex work, without deadly encounters between police and people in mental health crises?

Because Christians believe that every person is made in the image of God, our call is not to gloss over conflict, and neither is it to entrench hatred for the police. Our conviction is that endless cycles of violence and destruction are bad for all of us. We long for a new way of life because the carceral state is universally destructive.

The hope the church professes in Jesus Christ is for a peace that surpasses the peace of White moderation. It will be difficult and costly. It will divide natural allegiances and unite people in unexpected places. It will be angry. It will call systems of violence to account. And, in the end, it will set us all free.