Orthodox Jewish women scholars’ growing authority recognized in publishing

According to the Talmud, the first instructions on how Jews should celebrate the holiday of Purim were set down by one of its founders: Queen Esther, who with her cousin Mordechai helped save the Jews in Persia from the evil Haman. In writing her book on Purim, Esther became one of two women, with Jezebel, whose writing is recorded in the Bible.

Today, 50 years after the first woman was ordained a rabbi in America and 100 years after the first bat mitzvah, Orthodox Jewish women are being urged to write and publish more widely on religious topics than ever before, as publishers, schools, and websites are opening the way to make women’s scholarship and thinking more widely available—including two new programs named for Esther’s decision to publish.

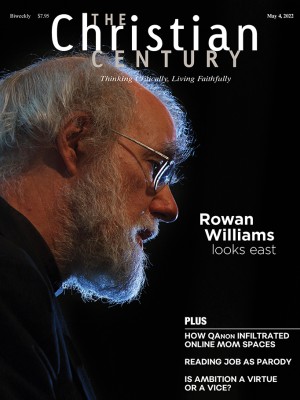

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At the end of May the Matan Women’s Institute of Torah Studies in Jerusalem will announce its first group of Kitvuni Fellows. Named for Esther’s command to her rabbis, “Kitvuni l’dorot” (“Record me for all generations”), the program invites female scholars and educators to develop books on the Torah, supporting them with workshops, access to experts, and a monthly stipend.

“It is time to make room on the bookshelf,” said Yael Ziegler, who became academic director at Matan last fall.

Opportunities for women to study Torah have been growing for decades, but without access to publishing, learning is rarely recognized. According to Ziegler, female scholars’ accomplishments “have not been reflected in the written Torah scholarship that has emerged.”

After more than 30 years of existence, Nishmat, a center for women’s Torah study in Jerusalem, published Nishmat HaBayit, its first collection of answers to women’s questions about Jewish law and the first book of Jewish legal responses authored entirely by women. The book contains entries on pregnancy and pregnancy loss, birth, nursing, and contraception. According to its website, more than 400,000 questions asked by women have been answered by the 160 female experts who have trained there.

Ziegler is conscious that the work of changing minds about women’s place in Torah study involves providing examples for younger women scholars. If publishers “fill bookshelves with that kind of scholarship that we are looking for, it will be a message to young women,” she said.

Encouragement to write is given to post–high school women in a three-year-old effort at Midreshet Lindenbaum, a yeshiva for Orthodox women started in Jerusalem in 1976. The program, Matmidot, tutors women to “cultivat[e their] ability to research and produce high-quality Torah scholarship,” according to its website.

Sally Mayer, who founded the program in 2019, said that one year her students decided to hold a year-end sale of books written by their teachers. Half of their teachers were women, but of the dozen books, only one was by a woman. The students asked, “Why aren’t women writing?” and Mayer says, “That has reverberated.”

Mayer recently started a journal for a select group of students to publish original research papers at the end of their year of studies. Mayer sees the value in this as something that will “enable those who have capability to spread Torah.”

An increasing number of initiatives are also being designed to encourage women who have four years of postcollege Jewish learning to write more. Last year, the Sefaria Women’s Writing Circle began providing coaching, editing, and peer mentorship, as well as a paid fellowship.

This year, the program Va’tichtov: She Writes (a quote from Esther 9:29) is being run by Yeshivat Maharat, an institution based in the Bronx, New York, that trains women to be Orthodox rabbas, rabbanits, or a title of their choosing at the end of their course of study.

At the 43-year-old Drisha Institute in New York, a six-week program will have workshops in fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and translation, according to No’a bat Miri, the program’s coordinator.

Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University, explained the importance of publishing in Jewish settings, saying: “Books are to power [just as] diamonds are to wealth, a visible display of who you are, what you are and what you can afford.”

He added, “Until there are women whose writing is read and disseminated and studied, there is a realization that women will not fully have been empowered in Jewish life.”—Religion News Service