December 22, Advent 4A (Matthew 1:18–25; Isaiah 7:10–16; Romans 1:1–7)

In Luke, Mary says that she’s a virgin. Do I believe her?

Many people I know who were raised in the church grew up with purity culture. I didn’t. The congregation that raised me was concerned with my spiritual formation, and all of us were involved in social justice causes. But I don’t remember much talk about when it was acceptable to have sex, or not. At home, my mother read the 1970s feminist classic Our Bodies, Ourselves with me. Instead of a set of rules tied up with shaky theology, I received “evidence-based information on girls’ and women’s reproductive health and sexuality.”

By the time I was in high school, a few of my Christian classmates were talking about abstinence. For some of my classmates in college as well, it seemed like the message that got through from adults in their lives was simply to avoid intercourse—a message that, among other things, demeaned the spiritual and emotional connection that other kinds of physical intimacy can form.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I developed a bit of an allergy toward the notion of virginity as an ideal. This continued through divinity school, especially as I read the early church fathers. It seemed to me that they extrapolated too much from the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ miraculous birth. I found them to be excessively concerned about virginity, equating purity with abstinence from sex.

Perhaps overcorrecting to avoid such a stance, for years when the doctrine of Mary’s virginity came up, I’d reply that it didn’t matter to my faith. Jesus’ birth could be extraordinary with or without it. In Isaiah, the sign God gives is that a young woman will bear a son named Immanuel, God with us. Likewise, Paul’s letter to the Romans describes Jesus as “descended from David according to the flesh,” which Luke and Matthew identify as through Joseph. No virginity necessary.

Then one time the topic of the virgin birth came up in conversation with a pastor friend. He pointed out that in Luke 1:34, Mary herself says she is a virgin: “How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?” (I appreciate how the King James Version stays close to the Greek here.) “I believe her,” my friend said.

While Matthew’s Gospel doesn’t let us listen in on Mary and Gabriel’s conversation, it does clarify that Mary’s child was “from the Holy Spirit.” Joseph is described as a righteous man. The Jewish Annotated New Testament notes that righteousness is concerned with just and ethical action and with following God’s commands in the Torah.

Joseph in that righteousness resolves to end his relationship with Mary because of her pregnancy. He doesn’t believe whatever she has told him about the child’s conception. Or maybe he doesn’t even ask her. Joseph doesn’t expect anyone else to believe Mary either; he expects she would be publicly disgraced.

Dwelling on this passage of scripture made me recall the Protoevangelium of James. This second-century Christian text begins before Mary’s birth and goes through her adolescence. Mary grows up in the temple in Jerusalem and is charged with preserving her virginity. Everyone around her undertakes great efforts to make sure that she is not defiled, that her purity so defined remains intact. After Jesus is born, the midwife declares that salvation has been brought forth to Israel—because she has seen that Mary is still a virgin even after childbirth. This text is also the source of the tradition that Jesus’ siblings are the biological children of Joseph but not Mary.

Unlike the canonical Gospels, the Protoevangelium of James gives us both Mary and Joseph’s angelic conversations in a single narrative. Except that by the time Joseph confronts her, 16-year-old Mary has forgotten what Gabriel told her. Yet still she defends herself against Joseph’s accusation of infidelity: “I am innocent and I do not know a man.”

In divinity school, I had to translate this passage for a Greek exam. (The teacher assigned noncanonical texts for exams, presumably because students might have large sections of the New Testament memorized—not a concern in my case.) It has stuck in my mind ever since because of its depiction of Joseph’s anguish, which is so much more dramatic than in Matthew. When Joseph sees Mary’s swollen belly, he strikes his own face, throws himself on the ground, and cries bitterly. He has an extended interior monologue about how to respond to what he assumes is her sinful behavior. He considers the possibility that “the child in her may be angelic,” yet he still plans to dismiss her quietly. He doesn’t believe her.

The Protoevangelium of James is not part of the canon. But something like that conversation between Joseph and Mary likely would have happened, even if the Gospels of Matthew and Luke don’t include it. Any way you shake it out, Joseph doesn’t believe Mary. It takes an angel of the Lord to command him not to dismiss her, quietly or otherwise. God convinces Joseph to believe Mary. He wasn’t inclined to do it on his own.

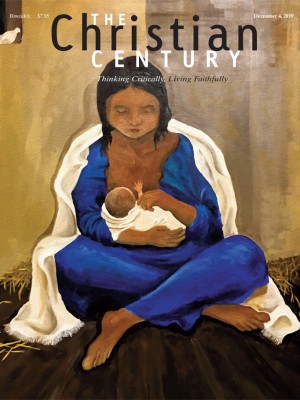

Preachers often highlight Mary’s marginalized social position: God chooses to become flesh through an unwed teenager. God chooses to become flesh through a girl whose people are living under occupation, through someone who is not a citizen of the empire.

God also chooses to become flesh—to be Immanuel, God with us—through a woman whose testimony was not believed.