Who are you? Almost every professional development setting I have been in over the last decade has at some point queried the participants about their personal brand. I’m an older millennial, so my investment in a virtual audience and platform is readily presumed. Online activity now lines the fabric of our culture. One’s social media “success” is now often a critical key to procuring everything from book contracts to speaking opportunities.

Who are you? Living in a world in which the depth of capitalist logic and technology has imbued our very lives with the potential for commodity and celebrity, the answer to this question can often be flattened to an at sign, a screen name, a web presence. We are (and are expected to be) on display in unprecedented ways. Identity is mitigated through screens that either draw us intimately near to or push us distortedly further from some sense of authenticity, some sense of truth.

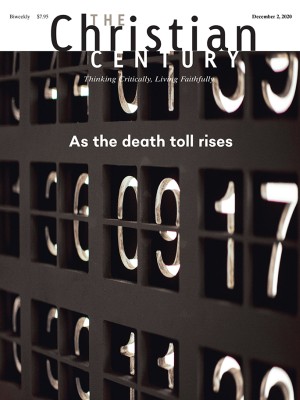

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

John the Baptist is anything but mainstream. But ironically enough, his eccentricity makes a remarkably compelling branding case. No, camel hair clothes are not an avant-garde fashion statement, and his diet of locusts and honey does not spark the latest sustainable eating trend. But John is deeply connected to the following he creates. His persona meets the main criteria for building a platform today. His messaging is clear and consistent; he stays in his lane; he speaks with singular authority and palpable authenticity. His commitment is its own brand, occupying the sweet spot where purpose meets passion. He is tapped into his own potential, and he knows his “why.”

And yet, there is something that isn’t quite legible. Again and again, John is asked who he is and what boxes he checks. He presents a conundrum, and he is ruffling enough feathers to attract attention from those more inclined to function as gatekeepers than to really pay attention to his message.

John remains steadfast despite the undertone of critique. Despite being likened to a genealogy of greatness, he maintains his commitment to the power of God and to manifesting his message through the work of transformation and liberation. He is marked by raw authenticity and deep humility. He isn’t interested in clout or in the accolades or affirmation from systems committed to anything other than freedom. His voice speaks the love of community and of kinship, of accountability and invitation, to join in the revolution he knows is to come and is already here.

Across the Gospels we see John working beyond the boundaries of traditional authority and bucking expectations as he rallies others to follow Christ. He doesn’t just speak of the behaviors of advocacy and justice; he lives them. He is in the trenches, committed to new possibilities and new life, baptizing indeed. We already know that he will be imprisoned out of fear for his message, that his life will be grotesquely and abruptly ended because of his work.

In a world that constantly demands we say something about ourselves, what does it mean to use our platforms, our power, our privilege—whether at the dinner table or to throngs of followers—to amplify something greater than our personal endeavors? To be an Advent people, not just pointing to Christ but living like Jesus is to come and is already here? To follow a Messiah who has no problem turning over tables and tearing down systems and speaking truth to power and abolishing the structures that do not serve all people? John reminds us of who we are to be, as someone committed to the fullness of the way—even if he does not live to witness it completely for himself.

The start of a new calendar year is often marked by the energy to ask and again pursue who it is we want to be. Perhaps the accounting of a new Christian year might best be marked with the energy to ask and again pursue who it is we are called to be. To give an accounting of ourselves—of the things we say, the resources we have, the people we value, and the love we seek to live by.

Are our voices crying out through the wilderness that is this country, this world? Are we laying the groundwork that prepares the way for something bigger than personal gain? Are we, individually and collectively, resisting the temptation to be so bound by the market that our baptisms—our death and resurrection in Christ—have been lost to amnesia? Do we find ourselves listening to the prophets in our midst, or are we satiated with the perfected image we see online?

Who are you? What do you say about yourself? Perhaps these are questions that can only be answered if we consider Christ’s own: “Who do you say that I am?”